It seems appropriate for me to post this article just as the weather in my region turns from cool and wet, thunderstorms and flooding, to heat wave warnings for the next week, a return to normal for this time of year.

Most Australians will know that Australia is home to some of the oldest surviving, continuous cultures in the world with our First Nations living and thriving on this continent for some 60,000 years. The previous article highlighted some of our First Nations’ knowledge about the seasons and the environment, particularly at this time of year. This knowledge and seasonal cultural practices were disrupted and often permanently eradicated by British colonialists, who imposed their own beliefs, cultures, traditions and practices on the country that was to become Australia. For those who might be unfamiliar with our history, Wikipedia provides a good explanation of Australia’s early British colonial period.

British traditions and practices often sat awkwardly against Australia’s seasons and environment, none more obvious as Christmas, which falls in the middle of our very hot Summers. Even now, there is still a struggle between imported Christmas traditions from the Northern Hemisphere, clashing with Summer in the Southern Hemisphere. It is rather odd to be singing about and decorating with themes of winter, snow, cold, warm food and drinks, while we are sweltering under the hot Summer sun. It would have been quite a big culture shock for the British, especially those early colonists. Let’s explore how the Australian colonists celebrated this time of year.

NOTE: This entire blog is dedicated to reviving as many seasonal practices from my own Western and Northern European background within the appropriate seasonal cycle here in Australia. I do this to try and reconnect with and understand my ancestral heritage, and the deep history of my people. This also includes telling the truth and not shying away from the ugly and difficult aspects of my connection to the place and Country I call home, through the brutality of colonisation. I will explore these difficult truths in January but for now, I want to acknowledge that talking about colonisation may hurt some readers and I acknowledge the validity of those hurts. I am deeply and forever will remain sorry for what has and is happening to this beautiful Country and its precious First Peoples. May you always be given the dignity, respect and honour you deserve, and may you, your cultures, and your connection to Country thrive so that we all may thrive together.

Colonial Christmas

The Daily Telegraph gives a good account of the first colonial Christmas in Botany Bay and by all accounts, it was pretty grim. Early colonists were entirely reliant on Britain for food supplies as they were unfamiliar with and unable to see the abundance of food in their new environment, their seed crops were destroyed by weevils and what little was grown, failed in the harsh environment. The entire colony was on strict rations, with hardly an exception for Christmas, unless you were a guest of Governor Phillip of course. Although even then, “Concerning that dinner, the least said the more generosity” reported judge advocate Capt David Collins about Christmas lunch in Sydney Cove in 1788.

During the early stages of colonisation, the religious celebration of Christmas was not popularly observed by the majority of colonists, other than for marriages or baptisms. Convicts generally came from the poorer classes who, even before being imprisoned, did not have time nor inclination to attend religious services and many had to work on Christmas Day for the wealthier classes. Pastor Richard Johnson complained in a letter to a friend in England that “inhabitants of Sydney Cove would prefer the erection of a tavern or a brothel than a church”.

Convict rations were abysmal with no dispensation for Christmas, they were provided with bread, salted beef or pork, perhaps fish, and yellow peas (pease). The next year in 1789, while the Governor and his guests dined on turtle and vegetables, the convicts were on reduced rations of salt pork, flour and pease.

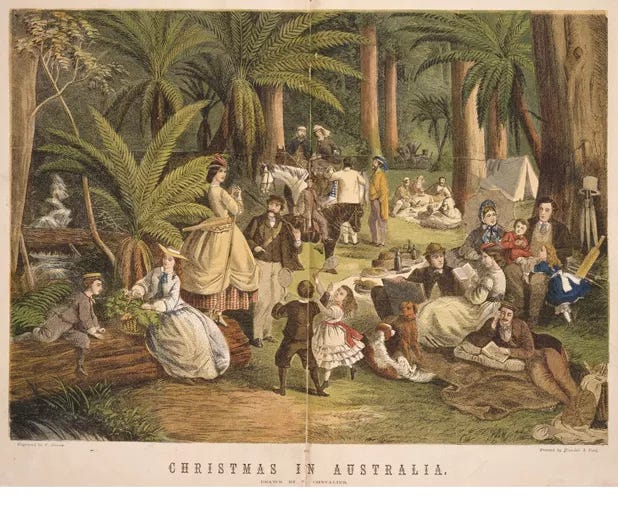

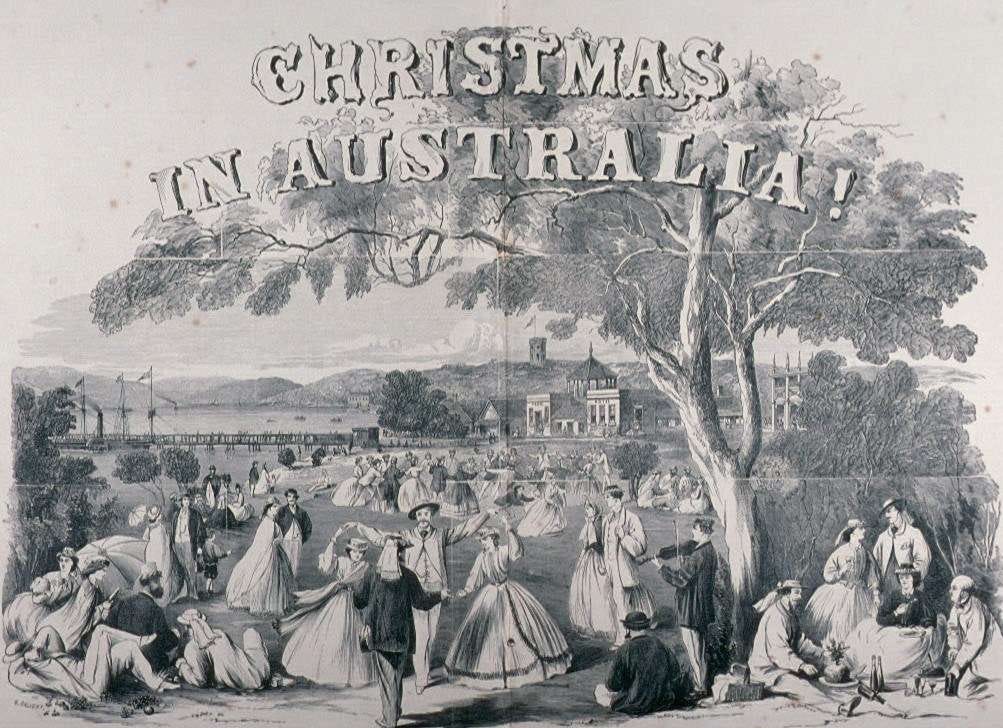

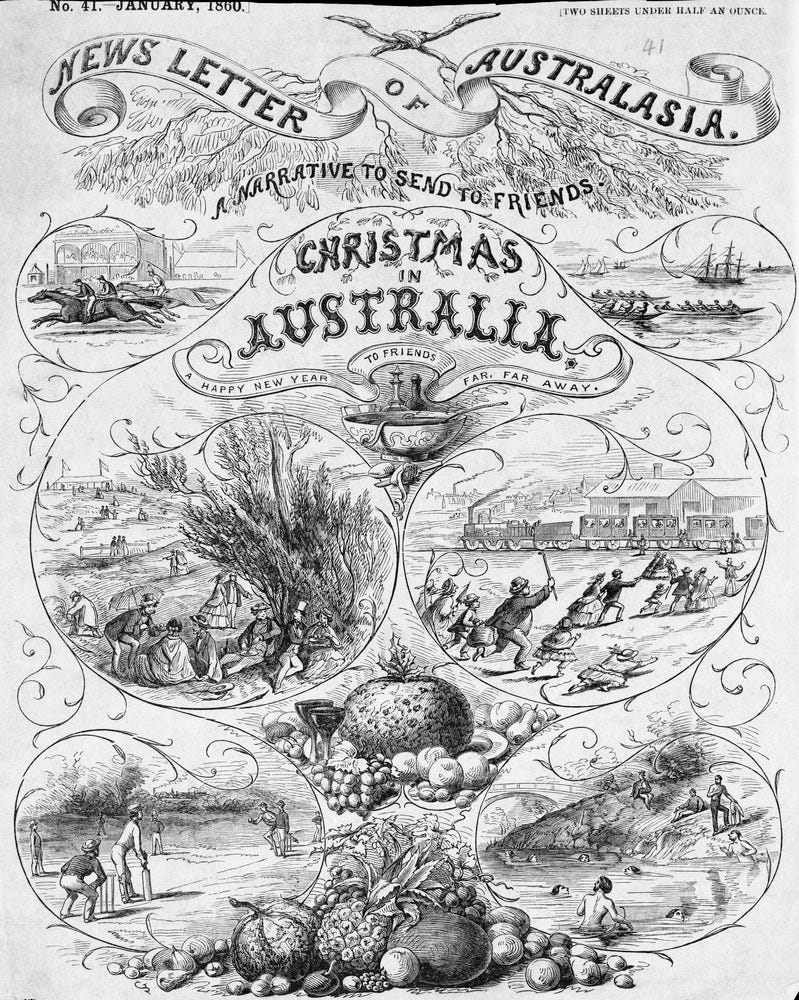

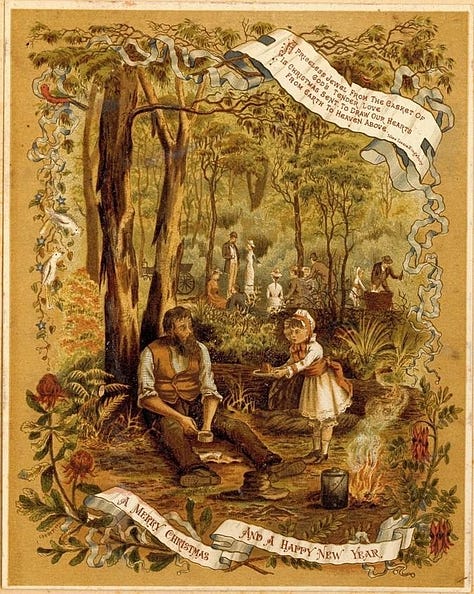

Over the next hundred years, conditions got better for the colonists as they started farming and taking more land from First Nations. Attempts were made to celebrate the positive aspects of Christmas in Summer.

The 1885 Sydney Mail described a Christmas scene in the colony:

… there is an air of Australian summer… no sense of snow or ice whatever… Fern fronds [and greenery] seem still to hold the sunshine and… the full glow of the morning and the full flood of light… streaming through the window and giving a full illumination to the room. Many thousand such Christmas scenes as this will NSW see this week, and many mothers and children will experience pleasure in finding their familiar Christmas preparations [shared throughout the colony]. From Sydney Living Museums Blog.

This newspaper article from Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers describes a typical Australian Christmas in 1872:

Adventide, despite the absence of the old world associations in the shape of carols, waits, snow, and frost, with the yule log, the mistletoe, the holly with its scarlet berries and the family gatherings, still continues a time of deep rejoicing in this sunny southern land. In the far bush and on the busy gold-fields, in the crowded city and the quiet hamlet, Christmas brings with it associations far different to its surroundings in the old world. They are characteristic of the new country, yet they lose nothing of their intensity in the change of locality and climate. Here the glad celebration of the season takes place, for the most part, under the broad canopy of Heaven; and picnics, athletic sports, and trips over the briny waves suffice as outlets to the feelings. In the wild bush, round the night fire, yarns are spun by the travelling stockmen ; and men live over again the scenes of their youth. Source: The Golden Christmas Cake in Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 1872

Here’s another article comparing the difference between the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere Christmas, this time from the Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 1852.

As if to vindicate the climate of the sunny South, the cool breezes which ushered in Christmas have given place to a sirocco from Sturt's Desert. What a vast stretch of the imagination is required to realize to the mind's eye an English Christmas, during a hot wind; or being subjected to a scorching summer heat to ruminate on snow balls, skates, chilblains, red noses, muffs, great coats, and comforters, and fancy one's self one of a dozen keeping the pot a'boiling down a long slide with the thermometer at 120. You can't do it, it's no use. What are prize oxen, prize sheep, prize pigs, rabbits, and poultry, misseltoe and holly, plum pudding, and snap dragon, speculation, and blindman's buff? they are only an indistinct dream, the memory of something disconnected with the present. In the north, all is top coat, and comforter, muff, tippet, and boa, piercing winds, and drifting snow, whilst here, if we become aboriginal in our habits, coolness would not follow. Our Christmas requires refrigerating to become enjoyable, instead of coughs, and pulmonary attacks, closed doors, stuffed key holes, and listed windows, we have langour, furious blasts, whirl winds, and doors wide open, courting every current, and in full length recumbency, open mouthed, we wait for a zephyr. Had we power, we would move that Christmas be postponed till this day six months, and that we do now proceed to consider these the Midsummer Holidays. Source: Christmas Times in the Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 1852

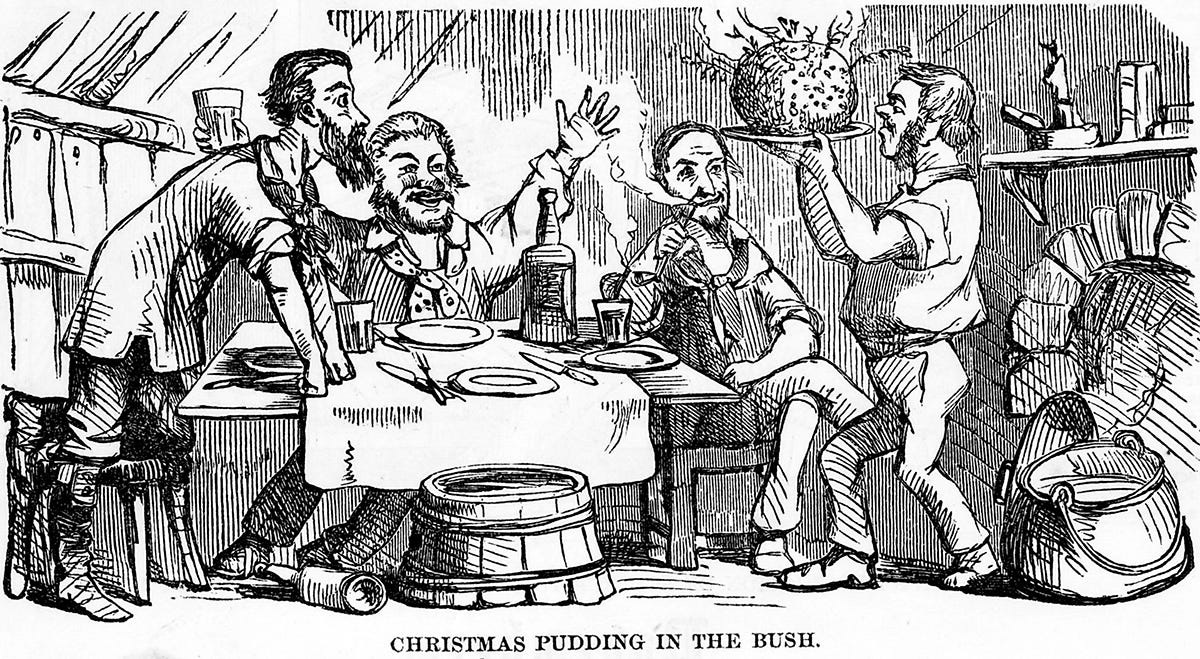

Bush Christmas

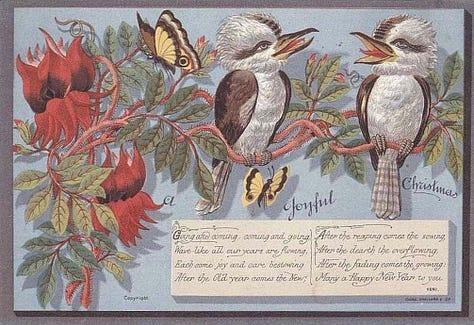

By the middle of the 1800s, British Australia was beginning to develop its sense of identity separate to Britain. The Bush Christmas became an icon around which the first Australian fables were built. Famous Australian poet and balladeer, Banjo Patterson, wrote his popular poem Santa Claus in the Bush, and Australian Christmas cards began to celebrate the uniquely Australian flora, fauna and Christmas weather.

Christmas Pudding

Although British Australians began adapting many of their old Christmas traditions to their new country, one particular tradition has been stubbornly (and joyfully) maintained. I have written about Christmas Pudding in a previous article on traditional Christmas desserts, from the season of Yule in June/July, Australia’s winter. Christmas pudding, as well as Christmas cake and mince pies, have retained their prominence in Australia and are still popularly baked or bought at this time of year.

In the early stages of colonisation, rations for military and civilians included flour, sugar and rum, with the addition of beef suet and raisins at Christmas to allow each household the ingredients for their Christmas puddings. As Australia’s free society became established, colonial merchants began importing and selling the ingredients needed for a ‘proper’ Christmas pudding, including brandy or rum, raisins, currants, figs, and almonds as well as spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon and allspice. Even miners on the goldfields in the 1850s, living in very basic conditions, worked to buy and prepare their precious Christma ‘pud.

Eventually, Australia was able to produce the fruit, alcohol and nuts needed for Christmas pudding and imports of these ingredients from Britain disappeared, although spices from the East Indies still needed to be shipped in. An article in The Conversation describes How the Christmas Pudding Evolved with Australia.

The importance of Christmas pudding for Australian Christmas traditions becomes very obvious if you search for ‘Christmas Pudding’ in the National Library of Australia’s Trove archives. Hundreds of thousands of newspaper and magazine articles giving recipes and favourite tips for Christmas pudding can be found spanning across all regions of Australia from the very earliest prints until now.

Tea and Sugar Train

While British Christmas traditions were being adapted to the Australian environment in the developing cities and towns across Australia, a train service began to spread unique Christmas traditions deep into rural and remote Australia.

The video (7:51mins) below about the Tea and Sugar Train was filmed in 1954 by the Commonwealth Film Unit and provided by the National Film and Sound Archive.

From Australian Trains

Perhaps one of Australia’s most loved trains, the ‘Tea and Sugar’ service commenced in 1915 to service some of the more remote places along the Trans-Australian route. Although it started by simply providing goods and services to workers in these remote locations, the service increased over time, providing more to a number of the isolated communities along the railway line between Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie.

For many who lived and worked in these remote communities, the train changed their lives. The ‘Tea and Sugar’ carried more than just that. The train also carried fresh meat in a butchers van as well as a variety of groceries and even provided pay and banking facilities. Best of all, the prices of goods on the service was comparable to the major towns and cities.

Firmly placing the service in the hearts of Australians, in the early 1950s the train even carried Santa Claus at Christmas time, distributing presents to children all along the railway route. The ‘Tea and Sugar’ was also used by the GPO for its mail run to these remote locations, with mail delivered to the station master where it could be collected by employees and families. The service soon expanded to include welfare services such as medical service, a children’s toy library and even a separate car housing a theatrette.

The arrival of the train was a cause for great excitement, breaking the monotony of day to day life in these isolated locations. The people in the towns often referred to the train’s arrival as ‘Tea and Sugar Day’ and many of the women celebrated the occasion by getting dressed up to meet the train at its siding in style.

Children’s book author Jane Jolly wrote a book about the joy of the Tea and Sugar train at Christmas.

From Tea and Sugar Christmas:

For 81 years, from 1915 to 1996, the Tea and Sugar Train travelled from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie once a week. It serviced the settlements along the Nullarbor Plain, a 1050-long rail link. It was a lifeline. There were no shops or services in these settlements. The train carried everything they needed—household goods, groceries, fruit and vegetables, a butcher’s van, banking facilities and at one time even a theatrette car for showing films. The biggest excitement for the children was the first Thursday of December every year, when Father Christmas travelled the line. He distributed gifts to all the children on the way, including those of railway workers, those in isolated communities, and station kids.

Do you have any old family stories about celebrating Christmas in early Australia? Please send them to Wheel & Cross or comment below.

Next week we’ll explore the more modern Australian Christmas celebrations including Santa on the Fire Truck (or in the back of a ute), hay bale decorations, native Christmas trees, Christmas at the beach, backyard cricket, and summery Christmas food.

Thank you SO much for the research you've poured into this piece and for providing all the absolutely marvelous links & photos!! I live in the US, so my experience of calendar rhythms has that stereotypical Northern Hemisphere vibe; and I've just recently been chatting with a friend who lives in South Africa, commenting on how different the seasonal celebrations are from the more 'mainstream' presentations of them. I've realized even more intensely how very Northern-centric our holidays are - I'm bookmarking this article to return to, as I continue to learn more about regional calendar customs!