As Summer ends and we move into the slower and cooler months of Autumn, our little garden denizens are busily stockpiling supplies for Winter. The mice and rats have become bolder, unselfconsciously ruffling through my rose trellis at night even with a torch trained on them. During the day, the bees have been engrossed in collecting nectar from my raspberry flowers and rosemary blossoms. It’s such a bountiful time in the garden, harvesting the fruits of the bees’ pollinating labour, and as the Summer nectar flow winds down, beekeepers are planning or have already finished their last honey harvests for the season.

Honey has an ancient and interesting history. It has been used by humans for thousands of years, not only as a food source, but also as an alcoholic drink, a medicine, a religious offering, and a symbol of royalty and wisdom. In this blog post, we will explore the history of honey’s use by humans, particularly in Europe and in European folktales and mythologies.

Ancient Honey Collecting and Beekeeping

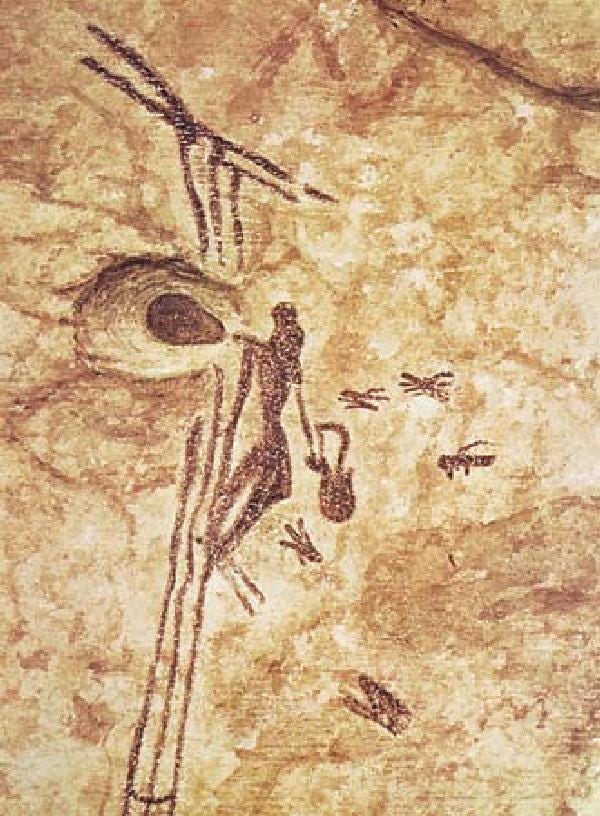

The earliest evidence of honey used by humans comes from rock art in Spain, India, Australia, and southern Africa, created in the upper Paleolithic period some 25,000 years ago. It’s more than likely that our hominid ancestors collected and ate honey, even our cousins the primates have been documented collecting honey from hives in the wild.

A 10,000 year old rock art from the Araña Caves in Spain, depicts people collecting honey from wild bee nests, high up on a cliff face.

Some cultures still practice this type of ‘honey hunting,’ such as the Gurung people in Nepal.

Although bees have never been domesticated, humans learned to manage them to more easily steal their wax and honey by creating manmade hives and developing beekeeping practices. These practices first appeared 8,500 years ago in Anatolia (modern day Turkey) and became widespread across Eurasia by 5,500 BCE. Evidence from written documentation as well as beehives made from pottery indicates that beekeeping evolved into an industrial scale enterprise in ancient civilisations such as Egypt, Sumer, Assyria, Babylonia, the Hittite kingdom, and as far East as China.

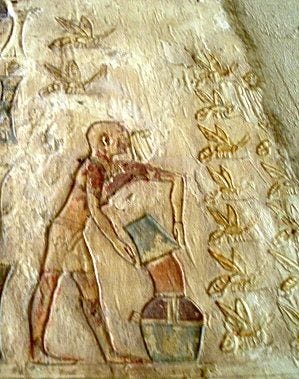

Honey was particularly important in ancient Egypt. It was found in ancient Egyptian tombs, where it was used as a gift to the gods and as an ingredient in embalming fluid. The ancient Egyptians also used honey as a sweetener and as a medicine for various ailments. The bee was a symbol of the pharaohs and featured frequently in hieroglyphs. The Egyptian Goddess Neith (Great Mother of the Sun) and mother of all the gods, was known as Mwt-Neit, ‘The Bee’ and her temple was known as the House of the Bee.

The ancient Greeks and Romans also valued honey for its nutritional and medicinal properties. They used honey to make cakes, cheeses, wines, and meads. They also offered honey to their gods and goddesses, such as Zeus, Apollo, Artemis, and Aphrodite. Honey was associated with wisdom, poetry, and love in Greek and Roman mythology. For example, Zeus was fed with honey as a baby by the nymph Melissa (meaning "bee" in Greek). The Melissae were considered bee-nymphs in Ancient Greek mythology and priestesses of various Greek Goddesses in historical attestations. Apollo was the god of beekeeping and honey. Artemis was sometimes depicted with a bow and arrows made of beeswax. Aphrodite was said to have been born from the sea foam mixed with honey.

Honey, Bees and Beeking in Europe

In central Europe, before the art of beekeeping became common-place, farmers marked trees that contained hives to indicate their right to the honey in them. Some began to hollow out holes in the highest and straightest trees, climbing up to collect the honey. The old Russian name for a bee-man was dreva-lazecu, which means ‘tree -climber’ and the Lithuanian bitkopis, which means ‘bee-climber’.

As suitable trees around settlements became more scarce, hollowed out logs were hung in trees and eventually were placed on the ground, either horizontally or perpendicularly, in forest clearings. These hollowed-out logs are still used as hives in parts of Germany, Poland, Lettland and Russia, and are called Klotzebeute in German.

Slavic culture has many superstitions surrounding the keeping of bees.

Bees were believed to be the purest beings, the only creatures whose souls the devil can’t corrupt and beehives are the only place where the devil cannot hide. Even if the devil did somehow manage to hide in a beehive, St. Elijah, an important Slavic Saint, would never strike the beehive with his lightning, not even to kill the devil. Similarly, Slavs believed that lightning never strikes a tree with a beehive in it.

In the Balkans, it is believed that to ensure success, a new beekeeper must start with three beehives: one found (containing a wild swarm), one received as a present, and one stolen. It was considered very bad luck to sell bees. Horse skulls were often placed on top of beehives to protect bees from pests and diseases.

When a beekeeper died, it was important that the family or a neighbour inform the bees of their master’s death, which is a custom found throughout Europe, known as Telling the Bees. Often the bees were begged not to leave themselves and were even invited to the funeral, or food and drink from the funeral was left by the hive. The hive was also rotated to face the funeral procession and draped with a mourning cloth.

It was important for the beekeper to give bees away before they died to ensure the bee colonies’ prosperity as it was believed that bee colonies still belonging to the dead beekeeper would also soon die.

It is also a common Slavic belief that the soul of the deceased migrated into a bee, meaning that humans and bees have the same souls. This is reflected in South Slavic languages, where the word uginuti means ‘to die’ but is only used for animals while the word umreti also means ‘to die’ but is only used for people… and bees.

The first splinter made during the cutting of the Badnjak (Yule log, usually a young oak tree) is collected and usually placed next to the beehives to ensure fertility and prosperity. Another splinter was put into the Christmas cake, cesnica, and some of the cesnica dough was smeered on behives to ensure the health and prosperity of the bees.

Paraphrased from Old European Culture Blogspot

The video (5:18 mins) below features a traditional log hive.

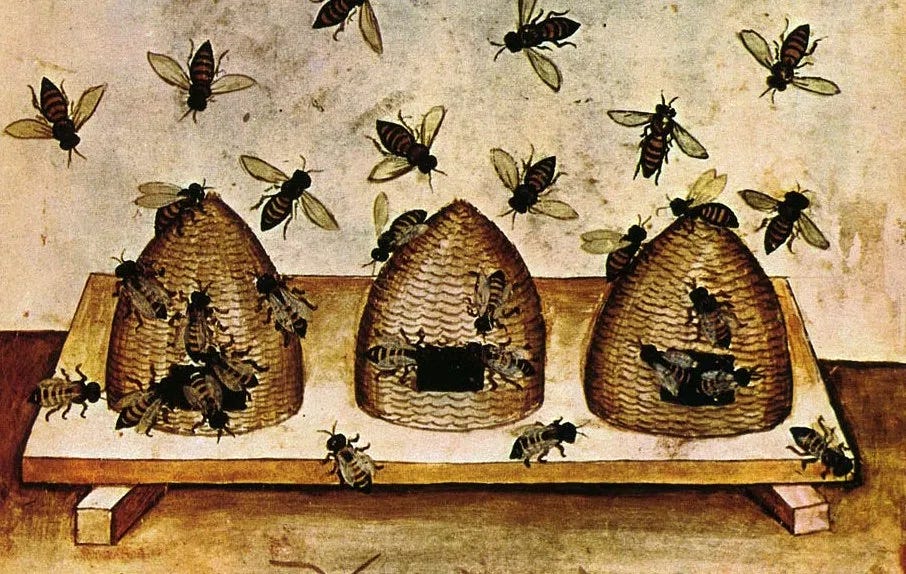

Tree log hives were commonly used across Europe until the skep hive became more popular. Beekeepers in Northern Europe transitioned from using logs to skeps around 800-1200 AD. These traditional hives are familiar to many through the high and folk art of the Middle Ages, when their popularity was at its peak. They were initially made from wicker and daubed with clay or cow dung, but eventually were made primarily from woven straw. The word ‘skep’ itself is derived from the Old Norse word skeppa, meaning basket. Skeps were often stored and protected from the elements in a ‘skep house’ or a ‘bee bole’ that stood alone or formed part of a stone or brick wall.

During the Middle Ages, beekeepers predominantly used skeps as their beehives. These dome-shaped baskets were effective and affordable, but they had limitations. Beekeepers couldn’t easily inspect the colony, making disease control difficult. Harvesting honey from a skep often meant destroying the hive because beekeepers had to cut open the skep to access the honeycomb. Skeps remained popular until the mid-1800s when the industrial Langstroth hive was invented, which allowed for easier honey harvesting and bee inspection.

Honey was an important source of food and medicine in medieval Europe. It was used to make breads, pastries, preserves, and beverages. It was also used to treat wounds, infections, coughs, sore throats, and digestive problems. Honey was considered a sacred substance by the Christian church and beeswax was used to make candles for religious ceremonies. Candles were otherwise made from beef tallow.

Honey also played a role in Western, Northern and Eastern European folktales and legends.

We’ve already explored some of the Eastern European, Slavic beliefs about bees in the previous paragraphs. In Northern European and Norse mythology, bees were connected to the goddess Freya, who was the patron of love, fertility and beauty. She was said to cry tears of gold that turned into bees when they touched the earth. Bees were also symbols of wisdom and eloquence, as they produced mead, the drink of poets and scholars.

Bee swarms were also connected to the Valkyries according to folklorist Hilda Ellis Davidson:

An Anglo-Saxon charm for taking a swarm of bees refers to the bees as sigewīf (victory women), and this seems likely to have been a name for valkyries, who like insects moved in troops through the air to accomplish this purpose.

Davidson, H. R. Ellis. 1988. Myths and Symbols and Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Manchester University Press. Source: mimisbrunnr.info

In Celtic mythology, bees were seen as travelers between worlds, bringing messages from the gods and the ancestors. They were also associated with druidic knowledge and magic, as well as healing and prosperity. Honey was used in many rituals and ceremonies, such as blessing newborns, weddings and funerals.

Mead

Mead is one of the oldest alcoholic beverages in the world, dating back to at least 7,000 BC and is made from fermenting honey with water, sometimes with added fruits, spices, herbs or grains to enhance the flavor. It was widely consumed in ancient times, especially in Europe, Asia and Africa and was considered a sacred drink by many cultures, such as the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Celts and Norse.

One of the most fascinating aspects of mead is its role in Norse mythology. The Norse believed that their gods were avid drinkers of mead, and that it gave them immortality, strength and wisdom. Mead was also associated with poetry and magic, as it was said to be brewed from the blood of a god named Kvasir, who was the wisest of all beings.

According to the myth, Kvasir was created by the gods as a symbol of peace after a war between two groups of gods: the Aesir and the Vanir. Kvasir traveled around the world, teaching wisdom to everyone he met. However, he was killed by two dwarves named Fjalar and Galar, who wanted to keep his wisdom for themselves. They drained his blood into three vessels: a cauldron called Odrerir and two vats called Bodn and Son. They mixed his blood with honey and made a mead that could turn anyone who drank it into a poet or a scholar.

The dwarves also killed a giant named Gilling and his wife by tricking them into drowning and crushing them with a millstone. Gilling's son, Suttungr, learned of their deeds and sought revenge. He captured the dwarves and threatened to kill them unless they gave him the mead as compensation. The dwarves agreed, and Suttungr took the mead to his home in a mountain called Hnitbjorg. He entrusted his daughter Gunnlod to guard it.

Odin heard about the mead and decided to get it for himself. He disguised himself as a mortal named Bolverk and went to work for Suttungr's brother Baugi, who owned nine slaves. Odin offered to do the work of all nine slaves in exchange for a sip of the mead. Baugi agreed, but he did not know where Suttungr hid the mead. Odin suggested that they should drill a hole in the mountain and see if they could find it.

Odin used his magic spear Gungnir to make a hole in Hnitbjorg. He then turned into a snake and slithered through the hole. He found Gunnlod guarding the mead in a chamber inside the mountain, charmed her with his words and seduced her. He persuaded her to let him drink from each vessel of mead: one sip from Odrerir, one sip from Bodn and one sip from Son. However, his sips were so large that he emptied each vessel completely.

Odin then turned into an eagle and flew away with the mead in his mouth. Suttungr saw him escaping and also turned into an eagle to chase him. A furious aerial battle ensued between the two gods. Odin managed to reach Asgard, where he spat out the mead into several vats. Some drops of the mead fell on Midgard, the world of humans, where they became the inspiration for bad poets.

Odin shared the mead with the other gods and with some chosen humans who were worthy of his gift. He became known as the god of poetry and wisdom, as well as war and death. Mead became a symbol of divine power and knowledge in Norse mythology.

Mead also played an important role in Norse culture and society. It was used as a drink of hospitality, friendship and alliance. It was served at weddings, funerals, festivals and ceremonies. It was also offered to honor the ancestors and the gods. Mead was believed to enhance courage, creativity and eloquence among those who drank it.

There are many old Norse festivals that feature mead as part of their rituals and traditions, such as Midsummer's Eve and Yule. There are also many meaderies that produce different varieties of mead, using local honey and natural ingredients. Mead is still drunk by many people to this day and is growing in popularity once more. For many, it is more than just a drink. Mead is a liquid history of human civilization, a nectar of the gods, and a source of poetic inspiration.

Next week we’ll continue to explore the natural highlights of the Autumn season with an article on the hedgerow and the hedgerow harvest.

It is just lovely to see Autumnal posts among the Northern Hemisphere-focussed posts starting to look toward Spring :)

Some fascinating stories and customs surrounding bees. Great article!