Today, in the Northern Hemisphere, the celebration of Imbolc, or Brigid’s Day heralds in early Spring. For us in the Southern Hemisphere, today marks the ancient Celtic celebration of Lughnasadh, the first harvest and the harvest of the grains. At this time of year, as the hot sun dries the nodding heads of grain to gold, farmers feverishly work to bring in their crops. Although harvesting grain crops such as wheat, oats, rye and barley, is now a highly mechanised and industrial process, there is still great value in remembering and celebrating old agricultural traditions that connect us to our European heritage, our food, the seasons and the beautiful land that we call home.

In today’s article, we will explore the celebration of Lughnasadh and Lammas, the tradition of corn dollies, folk songs related to the season and the grain harvest, a brief history of grain and grain farming, and the agricultural potential of native Australian grasses.

Lughnasadh and Lammas

Lughnasadh was an agricultural celebration honouring Lugh, the Celtic god of the harvest, and his foster mother Tailtiu, who cleared the land for farming in Ireland. It was a time to celebrate the artisanal skills, to hold fairs and games, and to make offerings to Lugh and his foster mother. Athletic games and competitions, such as wrestling, horse racing, archery, or chess honoured Lugh's talents and abilities, as well as being an opportunity for some communal fun. Climbing sacred hills or mountains, such as Croagh Patrick in Ireland, was customary for the devout and handfasting and weddings at this time of year were considered auspicious.

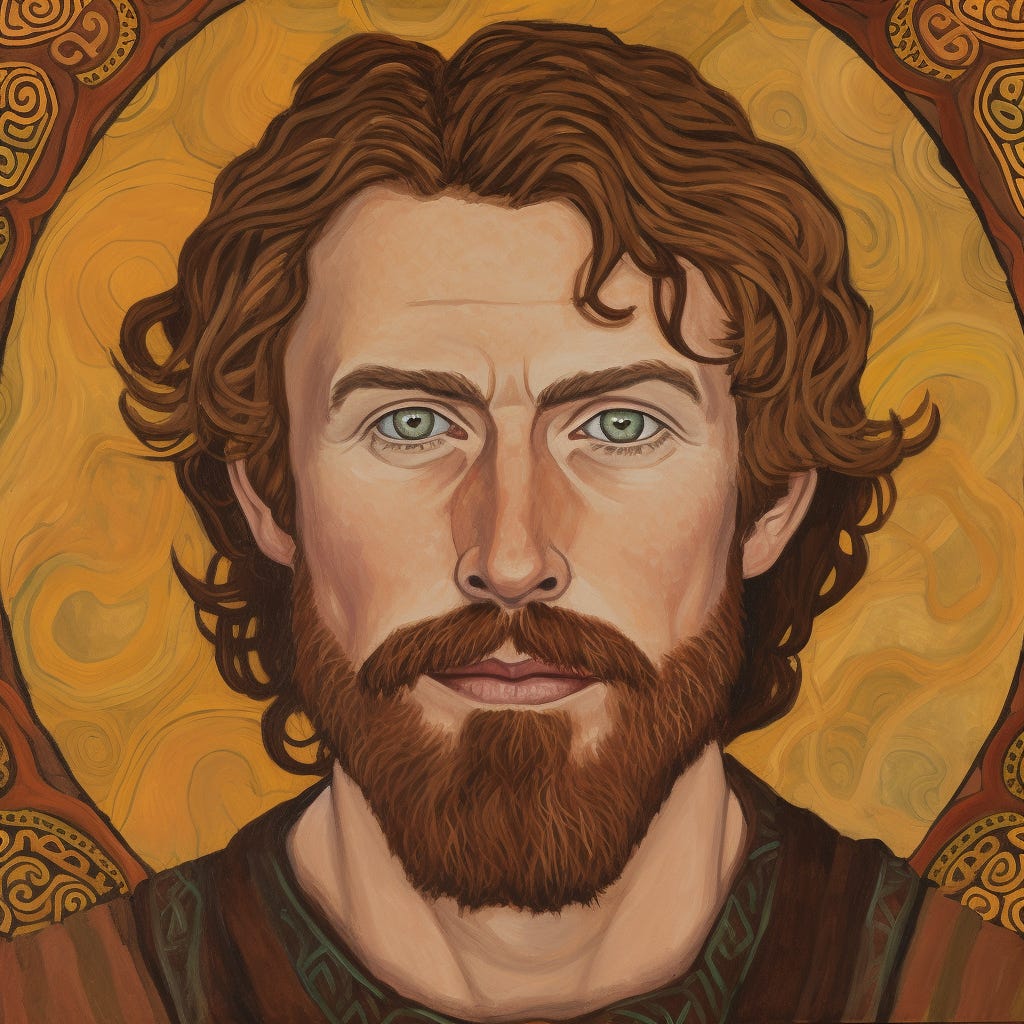

Lugh and Tailtiu

Lugh was not only the god of the harvest but also of light, fire, sun, crafts, skills, poetry, music, magic and war. He was known as Lugh Lámfada (long-armed) for his skill with throwing weapons, and Lugh Samildánach (skilled in many arts) for his mastery of various disciplines. He was born from the union of Cian, a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, and Ethniu (or Ethliu), the daughter of Balor, the leader of the Fomorians, a race of monstrous beings who opposed the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Lugh's birth fulfilled a prophecy that Balor would be killed by his own grandson. Lugh grew up to be a handsome and charismatic hero, who learned many skills from his foster fathers Manannán mac Lir (the sea god), Goibniu (the smith god) and Eochaid (the lightning god). He became the leader of the Tuatha Dé Danann and led them to victory against the Fomorians in the Battle of Mag Tuired (Moytura), where he killed Balor with his magic spear or sling. He also avenged his father's death by killing Balor's son Bres. Lugh's son was Cú Chulainn (Hound of Culann), one of the greatest heroes of Irish mythology.

Tailtiu was the goddess of agriculture, the foster mother of Lugh, and one of the most powerful deities of the Tuatha Dé Danann. She was the last queen of the Fir Bolg, a race of people who ruled Ireland before the arrival of the Tuatha Dé Danann. She married Eochaid mac Eirc, the king of the Fir Bolg, and later became the foster mother of Lugh, who was given to her by his grandfather, Balor of the Evil Eye.

Tailtiu was devoted to her son and to the welfare of her people. She undertook a massive project to clear the land for farming, which took a toll on her health and strength. She died of exhaustion after completing her task, but not before asking Lugh to hold a feast in her honour every year.

Lugh fulfilled her wish and established the festival of Lughnasadh, also known as the Tailtean Games, which took place on August 1st. The festival celebrated the first fruits of the harvest and featured athletic, artistic, and craft competitions. It was also a time for marriages, fairs, and trade.

Tailtiu's name lives on in the place where she cleared the land and where the festival was held: Tailte or Teltown in County Meath. She is remembered as a goddess of fertility, abundance, and sovereignty, as well as a symbol of maternal love and sacrifice.

Lammas

Lughnasadh was Christianised and renamed Lammas from the old English hlafmæsse, meaning "loaf mass". On this day, people would bring bread made from freshly harvested wheat to the church to be blessed by the priest. The bread was then used in various rituals to protect the harvest and ensure abundance.

Corn Dollies

One of the most common offerings or customs for Lughnasadh was the creation of a corn dolly, also known as a corn maiden, corn mother or old woman. Corn is the Old English name for grain crops (including wheat, rye, oats, and barley). It comes from Proto-Germanic kurnam meaning "small seed", which is also the source of Old Frisian and Old Saxon, German and Old Norse korn, and Middle Dutch coren, meaning "grain," and is the root for kernel.

A corn dolly was a decorative object made from weaving grain stalks together, usually in the shape of a human or an animal, though it could also take the form of spirals, braids, crosses or other symbolic shapes. It was believed that the spirit of the grain lived in the last sheaf of the harvest and that by making a corn dolly out of it, the spirit would have a home for the winter.

The corn dolly was then kept in a special place until the next spring when it was ploughed into the first furrow or burned to release the spirit. Corn dollies were also used as good luck charms and symbols of fertility and abundance. Different regions had different styles and names for their corn dollies and displayed them in different parts of the house depending on their local or even familial custom. Corn dollies created from the grain harvest were and still are customary throughout Northern, Western and even Eastern Europe.

In the neighbourhood of Danzig [Germany] the person who cuts the last ears of corn makes them into a doll, which is called the Corn-mother or the Old Woman and is brought home on the last waggon. In some parts of Holstein the last sheaf is dressed in women's clothes and called the Corn-mother. It is carried home on the last waggon, and then thoroughly drenched with water. The drenching with water is doubtless a rain-charm. In the district of Bruck in Styria the last sheaf, called the Corn-mother, is made up into the shape of a woman by the oldest married woman in the village, of an age from 50 to 55 years. The finest ears are plucked out of it and made into a wreath, which, twined with flowers, is carried on her head by the prettiest girl of the village to the farmer or squire, while the Corn-mother is laid down in the barn to keep off the mice. In other villages of the same district the Corn-mother, at the close of harvest, is carried by two lads at the top of a pole. They march behind the girl who wears the wreath to the squire's house, and while he receives the wreath and hangs it up in the hall, the Corn-mother is placed on the top of a pile of wood, where she is the centre of the harvest supper and dance.

James George Frazer, Scottish social anthropoligist and folklorist, The Golden Bough (1890)

You might like to try your hand at making your own simple corn dolly by following this video (2:27 mins).

First Harvest Folk Songs

Sonnenreigen (Lughnasad) by FAUN

This music video (3:46 mins) by FAUN is drenched in the seasonal symbology of First Harvest and Lughnasadh with subtitles translating the German lyrics into English.

John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn is a folk song that tells the story of a personified barley crop that is harvested, malted, brewed and distilled to make alcoholic drinks. The song has many versions and variations, but the main theme is the cycle of life and death, and the symbolic sacrifice of the grain for human consumption. The song is also a metaphor for the hardships and struggles of the common people, who are often exploited and oppressed by the powerful and wealthy.

Some of the earliest recorded versions of John Barleycorn date back to the 16th century, but the song may have older origins in pagan rituals or myths. The song has been sung by many folk singers and bands, such as Robert Burns, Traffic, Steeleye Span and The Pogues. The song has also inspired other works of art and literature, such as Jack London's novel of the same name, which is a memoir of his experiences with alcoholism.

The music video (8:31 mins) below features the band The Imagined Village with special guest Billy Bragg.

The Wind That Shakes the Barley

The song, The Wind that Shakes the Barley, was written by Robert Dwyer Joyce (1830-1883), a Limerick-born poet and professor of English literature. He published it in 1861 in a collection of his poetry, entitled Ballads, Romances, and Songs. It was inspired by the Irish Rebellion of 1798, also known as Éirí Amach 1798 in Irish and The Hurries in Ulster Scots. This was a failed uprising against British rule in Ireland, led by the United Irishmen, a revolutionary group that sought to create an independent Irish republic.

The song tells the story of a young rebel who is about to join the fight against the British forces. He is torn between his old love and his new love: his sweetheart and his country. He decides to leave her and seek the mountain glen where the rebels are gathering. But as he kisses her goodbye, a bullet from the enemy kills her in his arms. He buries her in the wildwood and vows to avenge her death. He later dies in battle and joins her in the grave.

The title of the song refers to the barley that the rebels carried in their pockets as provisions for their march. The barley also grew over the unmarked mass graves where the rebels were buried. The Wind that Shakes the Barley symbolises the spirit of resistance that lives on in Ireland, despite the oppression and bloodshed. It is a powerful expression of Irish nationalism and sorrow and has been sung and recorded by various artists, such as The Chieftains, Sinéad O'Connor, Solas, and Dead Can Dance. It also inspired the title of a 2006 film by Ken Loach, which depicts the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War.

The song is not to be confused with the reel of the same name, which is a lively instrumental tune often played at Irish sessions.

A Brief History of Grain

Grain is the starchy seed of selectively bred and domesticated grasses that have become staple foods in many cultures around the world. They include wheat, oats, rye and barley commonly grown and eaten in Europe, rice in Asia and corn in the Americas. The domestication of grains began around 12,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent region of the Middle East and spread throughout the world as humans, and their innovations migrated to different regions.

Today, grains are grown on a massive scale around the world, with wheat, rice, and corn being the most widely cultivated crops. The Industrial Revolution had an enormous impact on crop farming. Monocropping, mechanisation, fertilisers, pesticides and genetic engineering have led to improved crop yields and increased efficiencies. However, these gains in production have resulted in disastrous consequences for the environment, particularly on soil fertility, viability, and ecosystems.

In Australia, our already fragile soils have been decimated by intensive cropping that strips the soil of organic carbon and destroys soil ecosystems. Decreases in grain productivity and arable land due to soil loss, ecosystem destruction and climate change, as well as increases in grain production costs and artificial inputs, have led to growing interest in using Australian native grasses in cropping systems.

Australian native grasses are a diverse group of plants that have evolved over millions of years in Australia’s harsh and varying climate. Flour from native grains, such as millet, kangaroo grass and Mitchell grass, were important to many First Nations cultures and survival for thousands of years before colonisation. Their deep root systems and perennial growth have many benefits for the environment, such as preventing soil erosion, reducing groundwater recharge, and supporting native biodiversity.

Native millet (Panitum decompositum), in particular, was found to be easy to grow and harvest, easy to grind into flour, significantly more nutritious than wheat, and gluten-free. ‘Kangaroo Grass’ (Themeda triandra) can also be used for flour in the same way as wheat, has 40 per cent more protein than wheat, and is apparently quite tasty. It also stores more moisture than European crops and creates its own micro-climate in which native insects thrive.

These articles provide more information on the use of native Australian grasses for cereal cropping

ABC News (2022) - Native grains harvest brings together culture, food and regenerative farming

ABC News (2021) - Could native crop, kangaroo grass, become a regular ingredient in bread and help farmers regenerate land? for more information).

The Guardian (2020) - Australian researchers find native grasses could be grown for mass consumption

I wish you a bountiful Lughnasadh! See you next week, where we will explore the European folk tales and traditions of honey and bees. In the meantime:

May the rains sweep gentle across your fields,

May the sun warm the land,

May every good seed you have planted bear fruit,

And late summer find you standing in the fields of plenty.

Irish Farm Blessing

Great information, as always - and a beautiful blessing at the end. Good wishes of the season to you, too.