Happy New Year! If you celebrated New Year’s Eve in or are from an English-speaking country you most likely marked New Year’s Eve with a party, a countdown to midnight, maybe a midnight kiss, and probably loudly singing a drunken rendition of Auld Lang Syne. Where did this tradition come from and why is this time of year considered the New Year? Let’s explore the Western New Year traditions.

Marking the start of the New Year with a celebration or ritual is an ancient tradition common across most societies around the world, dating back thousands of years. The New Year was and is celebrated at different times of the year depending on the region and history of a particular place, but it was commonly linked to astronomical or agricultural cycles. The annual flooding of the Nile River marked the start of the New Year in ancient Egypt. In many cultures, the arrival of Spring and the Spring equinox signified the start of the New Year. Ancient Babylonians and Assyrians, including their modern societies from Iraq and Turkey, celebrate Spring and the New Year with the festival of Akitu. Ancient Persians, and their modern societies from Iran, celebrate the Spring festival of Nowruz. The Chinese have celebrated New Year to mark Spring for centuries.

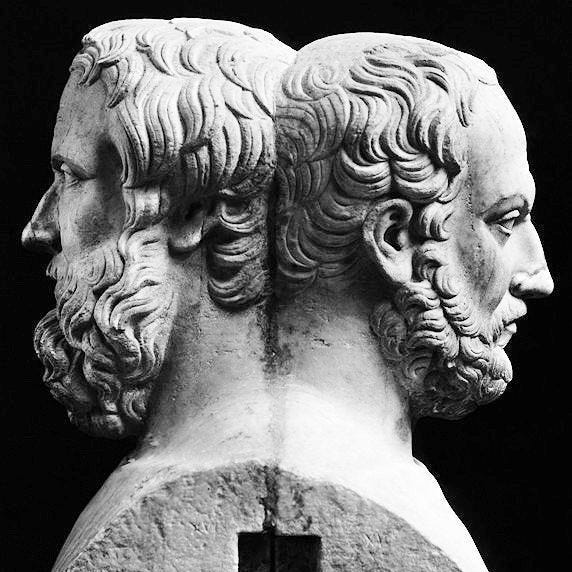

Ancient Romans

The ancient Romans also originally celebrated New Year in Spring, on March 1 according to the Roman Lunar calendar. The Julian calendar was created by Julius Caesar (calculated by the Greek mathematician and astronomer Sosigenes) in 45 BC to standardise calendars across the Roman Empire for civil and administrative purposes. The New Year was shifted to 1 January, aligning it with the ancient Roman celebration of Saturnalia and the month dedicated to Janus, the two-faced god of beginnings.

Saturnalia, named after the Roman god Saturnus, was a month-long festival of revelry and gift-giving that began on December 17, reached its climax on December 25 with Sol Invictus, the ‘Birth of the Unconquered Sun’, and culminated with the Kalends on January 1, marking the start of the New Year. It influenced the Western modern-day celebrations of Christmas and New Year. You can read more about Saturnalia in the article, Winter Solstice Traditions of the Ancient Celts, Romans, and Germanic People.

The British Isles

Local religious and agricultural calendars across Europe continued to mark the New Year around the Spring equinox until well into the 16th century. Once the Gregorian calendar was adopted in Europe, the celebration of New Year on 1 January became widely accepted. You can read more about the evolution of the Roman calendars that we currently use in the article, The Blue Moon and the Wheel of Months.

England, Wales, Ireland, and Britain's American colonies maintained 25 March as New Year’s Day until 1752, when they formally adopted 1 January as New Year’s Day, as well as replacing the Julian calendar with the Gregorian calendar. Scotland had previously adopted the 1 January date and Gregorian calendar in 1600, to align it with its mainland European allies.

In the Western world, we celebrate the New Year based on calendars developed by the ancient Romans, with traditions that are heavily influenced by the ancient Roman celebration of Saturnalia, its synthesis with Winter Solstice traditions from the Celtic and Germanic worlds, and more recently by the Scottish Hogmanay.

Hogmanay

Hogmanay is the Scots word for the last day of the year, New Year's Eve. Its exact origin isn't definitively known, but it's believed to have roots in various traditions and languages. Some theories suggest it's derived from the French phrase hoguinané, which means a gift given at New Year's. Others associate it with the Anglo-Saxon phrase haleg monath, referring to Holy Month, designating the Christmas period or the month of December. It is thought to have first been used widely following Mary, Queen of Scots' return to Scotland from France in 1561. Its origins are rooted in the Norse celebration of the winter solstice, known as Yule, which was celebrated in Scotland before Christmas became popular.

Hogmanay often involves a series of customs and festivities that can last for several days. Traditions include night-time parades and raucous parties on New Year’s Eve to ‘greet’ the New Year. They also include midnight fireworks displays.

An old custom that is still practised in parts of Scotland and the Scottish diaspora is known as first-footing, where the first person to enter a home after midnight brings gifts such as coal, shortbread, or whisky, symbolising good luck for the coming year. It is considered good luck for the first footer to have dark hair as blond hair was connected to Vikings who raided Scotland from the late 8th century AD and continued intermittently for several centuries, lasting until around the mid-11th century AD.

Other traditions that are still popular include singing Auld Lang Syne, a traditional Scottish song written by poet Robert Burns in the 1800s from an older Scottish folk song.

At Hogmanay in Scotland, it is common practice that everyone joins hands with the person next to them to form a great circle around the dance floor. At the beginning of the last verse (And there's a hand, my trusty fiere!/and gie's a hand o' thine!), everyone crosses their arms across their breast, so that the right-hand reaches out to the neighbour on the left and vice versa. When the tune ends, everyone rushes to the middle, while still holding hands. When the circle is re-established, everyone turns under the arms to end up facing outwards with hands still joined. Wikipedia

The video (4:25 mins) below provides a good summary of the history and rise in popularity of Auld Lang Syne.

The next video (3 mins) below features a beautiful rendition of Auld Lang Syne by Celtic Woman.

The tradition of singing Auld Lang Syne at midnight spread throughout the English-speaking world with Scottish emigrants along with other traditions such as:

cleaning one's house before the New Year to sweep away any bad luck

opening of doors and windows to let the old year out and the new year in

saining - sprinkling every room with water from a fresh stream then smoking each room with juniper smoke, similar to smudging.

A Welsh New Year’s Day tradition involves drawing the first water from a well on New Year’s morning and sprinkling people with the water using evergreen sprigs. The traditional Welsh New Year carol known as Levy Dew describes this tradition, as well as the custom of opening doors to let the New Year in and out.

Levy Dew

Here we bring new water from the well so clear,

For to worship God with, this happy New Year.

Chorus (after each verse):

Sing levy-dew, sing levy-dew, the water and the wine,

The seven bright gold wires and the bugles that do shine.

Sing reign of Fair Maid, with gold upon her toe;

Open you the West Door and turn the Old Year go.

Sing reign of Fair Maid, with gold upon her chin;

Open you the East Door and let the New Year in.

Traditional Welsh folk song popularised in 1934 by Benjamin Brittan

Wherever you are in the world, and however you celebrate, may you have a joyous and prosperous New Year, may you be blessed with peace and abundance, and as the Scottish say… “Lang may ya lum reek wi’ither folks coal” (Long may your chimneys smoke with other people’s coal).

Oh my goodness, this is fascinating!! Thank you so much in particular for that Welsh tradition and prayer - I've not seen that before. New year traditions really enamor me - especially with all the various "new years" floating around (like March 25, the Annunciation, as the new year!)