Samhain - Part 4: Creatures of Darkness

Witches, black-coloured animals and otherworldly beings

I hope you had a marvellous Samhain on Wednesday. In my household, the pumpkins were carved into Jack-O-Lanterns and placed at the front of the house, ostensibly to protect us from the spooky denizens of the otherworld but mostly because it’s a fun thing to do. The house was decorated for the season and photos of our ancestors placed on the walls.

Samhain dinner was prepared - pumpkin soup (naturally) with cheesy garlic bread and seven-apple crumble for dessert (seven different types of apples to celebrate the Autumn apple season) and Barmbrack Soul Cakes were baked. A place was laid at the table and food served to honour all of our dearly departed and those who are too ancient to remember but still precious and revered.

In this is the final article on Samhain we will explore the iconic beings that symbolise Samhain: witches; black-coloured animals like cats, dogs, corvids (ravens and crows), bats and horses; and finally creatures from the Otherworld who inhabit the darkness.

Witches

The history of witches is deeply intertwined with European cultures and folk practices. In pre-Christian times, witches were often revered as wise healers and practitioners of folk magic, wielding knowledge of herbs, potions, and rituals for the benefit of their communities. Some were occasionally sought out for more nefarious purposes, such as hexing or cursing. Most witches were women. Many lived on the outskirts of their communities or at the fringes of their societies, while others were important and respected community figures. Midwives tended to women during childbirth, and often provided perinatal assistance to women and their babies, or assisted women to end unwanted pregnancies. They commonly used herbs, rituals and spellwork in their practice and were often sought out for more than their midwifery skills.

Henwives were women who played a crucial role in rural communities, particularly in the British Isles. They were known for their expertise in raising poultry, but their role extended far beyond mere animal husbandry. Henwives were often seen as wise women who possessed knowledge of herbalism, healing, and midwifery. They were integral to the fabric of society, providing practical assistance and wisdom, and sometimes even delving into the mystical, offering guidance and foresight. Henwives are often present in folklore and fairy tales, particularly from the British Isles. Their social ties to their communities contrasts them with the archetype of the ‘witch in the woods’ who lives alone and away from ‘civilisation’. Terry Windling’s blog, Myth and Moor features an excellent article on henwives.

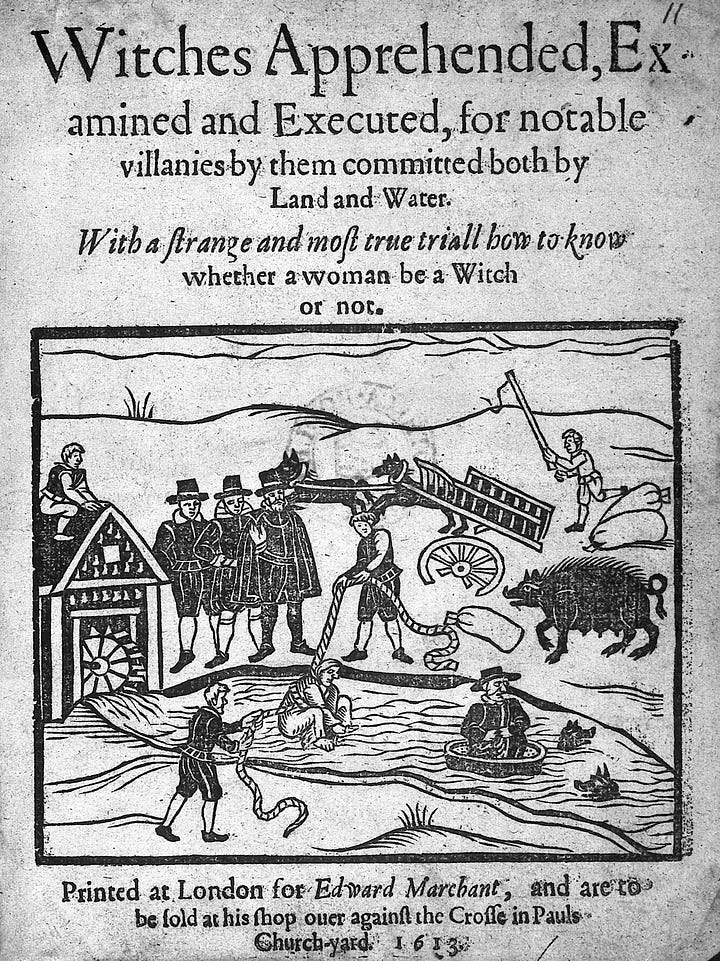

With the spread of Christianity, pagan traditions came to be viewed as heretical and were condemned by the Church. During the medieval period, the Church launched campaigns against witchcraft, portraying witches as servants of Satan who consorted with demons and engaged in malevolent acts such as casting curses, causing illness, and summoning storms. This demonization of witches reached its peak during the witch hunts of the early modern period, particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries, when tens of thousands of people, primarily women, were accused of witchcraft and subjected to torture, sham trials, and execution.

Samhain, as a liminal time when the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead is believed to be thin, became associated with witchcraft and supernatural phenomena. It was believed that witches and other practitioners of magic could harness the energy of the liminal space at Samhain to commune with spirits, perform divination, and work spells.

During the Christianization of Europe, many pagan beliefs and practices associated with Samhain were demonized and absorbed into the folklore surrounding witches. Samhain became conflated with the Christian holiday of All Saints' Day (November 1) and All Souls' Day (November 2), collectively known as Allhallowtide, and the association between witches and Samhain persisted. Samhain became a focal point for fear surrounding witchcraft rituals, both real and imagined.

Witches are iconic archetypes in myths, legends and fairytales across Europe:

Circe was a powerful enchantress in Greek mythology known for turning Odysseus’ men into pigs.

Hecate was a Greek goddess associated with magic, witchcraft, crossroads, creatures of the night and the moon, often depicted with triple heads representing maiden, mother, and crone.

Trivia was the ancient Roman equivalent of Hecate.

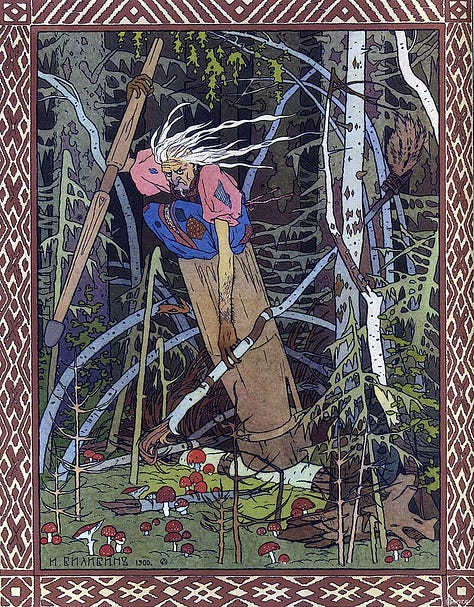

Baba Yaga is a fearsome witch from Slavic folklore, living in a hut that stands on chicken legs.

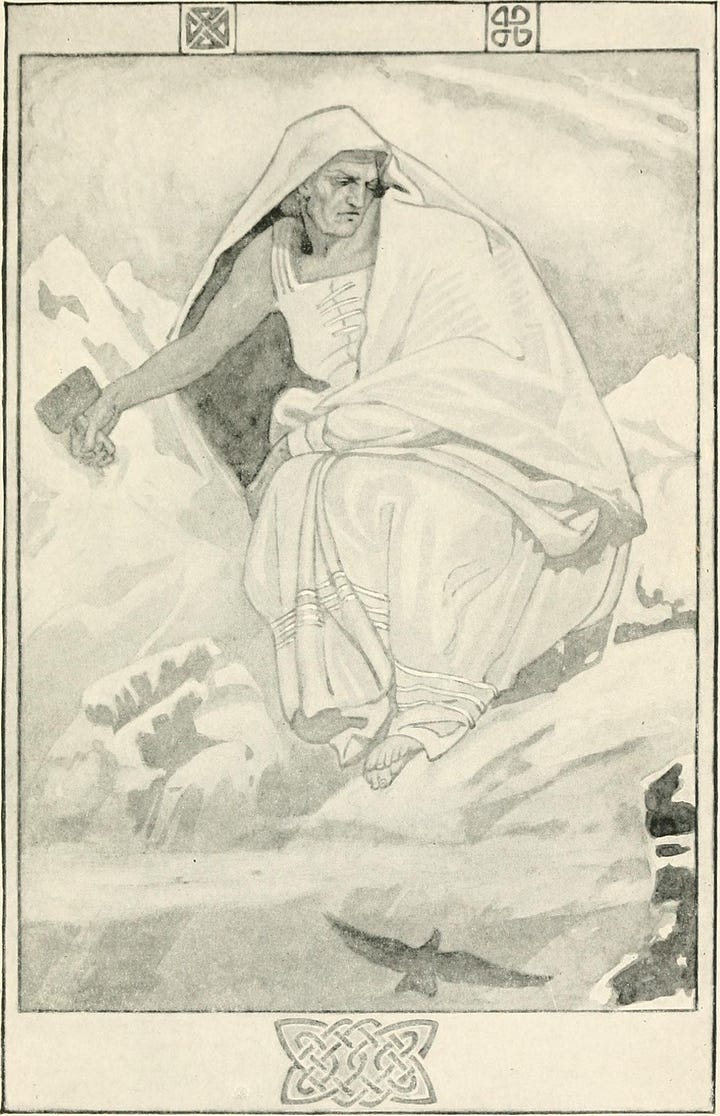

Cailleach is a hag or witch in Gaelic mythology, often depicted as an ancient and powerful figure associated with winter, storms, and the natural world.

La Befana is an Italian folklore character who delivers gifts to children on Epiphany Eve, and often depicted as a witch.

Lilith is considered a witch in Jewish folklore and is associated with the night.

Vǫlur/Vǫlva, Seiðkonur/Seiðkona and Vísendakona are various names for witches in the Nordic languages.

Witches remain iconic figures in popular culture, and have been featured in art, literature and legislation: from ancient Greek and Roman laws banning the use of magic to cause harm, to the early Christian era with The Witch of Endor recorded in the book of Samuel written between 931 BC and 721 BC, to classical art and literature, as well as modern movies and books featuring witch characters. Disney has produced many animated movies featuring witches. This short (1 min) clip features a tongue-in-cheek advertisment for ‘witches brew’ in the Disney/Pixar movie Brave.

In modern times, the image of the witch has undergone a transformation, with witches reclaiming their identity as practitioners of nature-based spirituality and proponents of feminist empowerment. Samhain remains an important holiday in contemporary pagan and Wiccan traditions and Halloween, replete with witches costumes and decorations has become a favourite secular celebration.

Hey-how for Hallowe'en!

A' the witches tae be seen,

Some are black, an' some green,

Hey-how for Hallwe'en.

Traditional Scottish VerseCreatures of Darkness

Black coloured animals such as cats, dogs, corvids (ravens and crows), bats and horses have been associated with Samhain and Halloween for many thousands of years.

Black Cats

There are few creatures as iconic during Samhain and Halloween as black cats. Black cats have long been associated with witchcraft and magic in European folklore. In Scottish lore, black cats were considered lucky and one arriving at a home signified prosperity. In other parts of the British Isles, a black cat crossing your path was considered unlucky, or even an omen of death. During the Middle Ages, they were believed to be witches' familiars, or supernatural entities that aided witches in performing spells and rituals. As a result, black cats became symbols of bad luck and were often feared and persecuted. In Nordic legends, black cats symbolised good fortune and the goddess Freya’s chariot was pulled by two large black cats.

Black Dogs

The black dog is also an iconic figure during Samhain, especially in the British Isles. In Celtic mythology, the black dog is seen a both a harbinger of doom and guardian of the underworld. It roams sacred sites, and serves as an omen of death or as a psychopomp, escorting newly deceased souls from Earth to the afterlife. In Nordic and Germanic mythologies, the mythical wild hunts, rampaging hordes of gods or witches on horseback, are often accompanied by baying black hounds. The (12:03 mins) video below from Monstrum describes origins of the hounds of hell.

In English folklore the appearance of a black dog was often associated with specific locations such as crossroads or graveyards and seeing a black dog was believed to fortell one’s own demise. One of the most famous examples is the Black Shuck, a ghostly black dog that is said to roam the East Anglian countryside. It is described as being unnaturally large, with glowing reg or yellow eyes and is thought to be the incarnation of a hellhound. The BBC clip (6:39 mins) below explains the origin and appearance of the Black Shuck.

Corvids

The glossy black and highly intelligent corvids (crows and ravens) have been connected to Samhain and Halloween for many ages. Their black feathers associated them with death and the underworld, as did their habit of eating carrion and killing young and weak animals. They could also cause great damage to agriculture and food production, especially in large numbers as they consumed sown seeds and growing crops. Scarecrows were created to keep them out of fields.

Often despised by farmers, they were also feared by many as they frequently gathered near ancient burial mounds and sacred sites and their presence was seen as a sign that spirits were nearby. Some European cultures also believed that crows and ravens were psychopomps, guiding souls to the afterlife. Corvid caws and movements were interpreted as omens, foretelling death or significant events. In some parts of Scotland, it is still believed that a crow resting on the roof of a house at Samhain is an ill omen portending death to someone in that household. Crows and ravens were often linked to witches and magic. The Norse god Odin had two crows, Huginn (thought) and Munnin (memory), who brought him news of all that happened in Midgard (the world of men). Crows and ravens were commonly considered to be fylgja (familiars) of Nordic vǫlva or seiðkona (witches).

Bats

Bats are also symbolic of Samhain and Halloween. They hunt and fly through the air at night and although harmless to humans, their facial features can be frightening or look eerie. They also carry diseases and are feared by many who believe they are associated with the Devil, evil spirits or witches. Pre-Christian Celts would light large bonfires at Samhain to ward of evil spirits, and these fires attracted insects. Bats, in turn, swooped around the flames, feasting on the bugs and they were thought to be the embodied spirits of the returning dead. Folktales about blood-sucking bats, and vampires shape-shifting into bats, originating from Eastern Europe spread throughout the rest of the continent and the British Isles through the long-standing Samhain and Halloween tradition of scary story-telling.

Black Horses

The black horse is associated with symbols of death and the underworld in many European cultures. In ancient Greece, Hades, the god of the underworld rode a black horse. Similarly, Hel, Queen of the Nordic underworld realm of Helheim, rode a black horse named Hrimfaxi, which means ‘frost mane’. Hrimfaxi is said to bring the cold and darkness of Helheim with him as he travels through the night sky. The Nordic and Germanic gods and later witches were said to ride black horses with fiery eyes on their wild hunts.

In Celtic mythology, black horses were seen as harbingers of death and they carried souls to the afterlife. In Ireland, folklore tells of the Dullahan who rides on the back of a flame-eyed black horse while holding his decapitated head. Kelpies are shape-shifting water spirits from Scottish lore that commonly take the form of a striking black horse appearing in bodies of water throughout Scotland. They were said to crave human flesh and would lure unsuspecting humans onto their backs, before racing into the water and drowning their victims. In Christian folktales, the black horse is one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, representing famine and death. These myths, legends and folktales surrounding black horses are intertwined with the symbology of Samhain and Halloween.

Otherwordly Beings

At this time of Samhain, when the veil thins between this world and the otherworld, creatures from uncanny parts slip through and mischief is made: skeletons come to life, ghosts roam the earth, headless horsemen wheel and turn at crossroads, witches cast spells and work magic, the faeries (ghosts of the Tuatha de Dannan) are abroad on mysterious pilgramage, screaming hordes and baying dogs echo in the deep night and many of these otherwordly beings crave the human soul or even human flesh! Explore the selection of mini-documentaries below from Monstrum

I hope you enjoyed this series on the spooky and pumpkin-filled season of Samhain/Halloween. Next week is our final article for the Wheel & Cross year, stay tuned to explore European folklore about nuts and apples and an announcement for the new Wheel and Cross year.

Looks like you enjoyed a bountiful Samhain celebration x

I love seeing how you're celebrating these traditions in the southern hemisphere.