The Origins of Christmas

Traditions borrowed from the old winter solstice and Nordic Yule celebrations.

Here in the Southern Hemisphere, we are celebrating the winter solstice but in the Northern Hemisphere, the winter solstice occurs in December, a few days before the celebration of Christmas. Southern Hemisphere Christmas traditions are a little different since we celebrate in the middle of our summer and we’ll delve into these summer traditions closer to December. For now, in recognition of Christmas’ pagan winter solstice roots, let’s take a look at the origins of Christmas, from the spread of Christianity to the influence of the Vikings, the repression of Christmas traditions by the Puritans, and its revival in the Victorian Era.

The Christ Mass

The spread of Christianity in Europe began in the 1st century CE. It originated in the eastern Mediterranean region, specifically in the Roman province of Judea (modern-day Israel), and quickly gained followers within the Roman Empire. The early Christian movement expanded primarily through the efforts of the apostles and missionaries who travelled across the Mediterranean, spreading the teachings of Jesus Christ. Over time, Christianity gained acceptance and eventually became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, leading to its spread across Europe and beyond. The process of Christianization took several centuries, with different regions and peoples adopting the faith at different times.

In a previous article, we learned about the Winter Solstice Traditions of the Celts, Romans and Germanic People. As Christianity spread across North and Western Europe, the early Church sought to integrate and redirect the existing winter solstice traditions to align with Christian beliefs. By strategically adopting and adapting elements of the solstice celebrations, such as the date and certain customs, Christianity aimed to ease the transition for the local populations and provide a familiar framework for their spiritual practices. The timing of Christmas, for instance, strategically coincided with the winter solstice, allowing Christian festivities to replace the traditional pagan observances. Many of the rituals, symbols, and themes associated with the solstice, such as the lighting of candles, the decoration of evergreen trees, and the emphasis on light and rebirth, were gradually infused with Christian symbolism and given new meaning within the context of the birth of Jesus Christ. This process of assimilation and transformation not only helped spread Christianity but also allowed the local cultures to retain certain aspects of their cherished winter traditions within the framework of the new faith.

It might be surprising to learn that the date of Jesus’ birth was an invention to Christianise the winter solstice mythology. Niall Edworthy wrote in his book, The Curious World of Christmas (2008), that:

Nowhere in the Gospels or the writings of the early Christians is there any mention of Christ’s birthday. It was several centuries after his lifetime that the date became a matter of conjecture and argument. This was partly because early Christians had no interest in birthdays. The Epiphany (today, January 6) was of greater importance in the Eastern Churches, this was the day for celebrating Christ’s baptism; in the West it was to commemorate the manifestation of Christ’s glory and his revelation to the Magi.

Some early Christians even took exception to the recognition of birthdays because it distracted from their more significant “death days,” when saints were martyred and Christ had given his life for mankind. Exactly when the Church decided upon December 25 as the birth date of Jesus is unclear, but it almost certainly came to be accepted as that during the fourth century, possibly during the reign of Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor (p. 15).

By the time Viking raiders began their attacks on Britain and Ireland in the late 8th Century, the Christian celebration of Christmas was entrenched.

Vikings

The Vikings came from Scandinavia, what is now Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. They raided England by sea and river in their famous fast-moving ships, targeting the treasures kept in English monasteries and taking slaves, particularly in Ireland. Some eventually settled in England becoming traders, farmers, and fishermen. They established the Danelaw in the East of England after their defeat by the Christian English King Alfred the Great in 878 AD. The influx of ‘Danes’ or ‘Norsemen’ reintroduced customs, celebrations, and traditions to England, which were similar to the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons’. We will explore these Nordic traditions centred around Yule in future articles.

This 9:18 minute video by World History Encyclopedia provides an excellent summary of the Nordic origins of Christmas.

W. F. Dawson wrote about the effect of the earlier Anglo-Saxon invasion of Great Britain on the Roman Christian celebration of Christmas in his book Christmas: Its Origins and Associations (1901):

The outgoing of the Romans and the incoming of the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes, disastrously affected the festival of Christmas, for the invaders were heathens, and Christianity was swept westward before them. They lived in a part of the Continent which had not been reached by Christianity nor classic culture and they worshipped the false gods of Woden and Thunder and were addicted to various heathenish practices, some of which are mingled with the festivities of Christmastide… The Anglo-Saxon excesses are referred to by some of the old chroniclers, intemperance being a very prevalent vice at the Christmas festival. Ale and mead were their favourite drinks; wines were used as occasional luxuries.

Following the cessation of Viking raids and the establishment of the Danelaw, Danish rule was finally ended by the Norman invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066 AD. Although descended from Anglo-Saxons who settled in Francia and Normandy, the Normans were renowned for their Catholic piousness and England again became a Christian nation. Christmas celebrations returned, though re-coloured with Christian beliefs and converted symbolism.

A Puritan Christmas

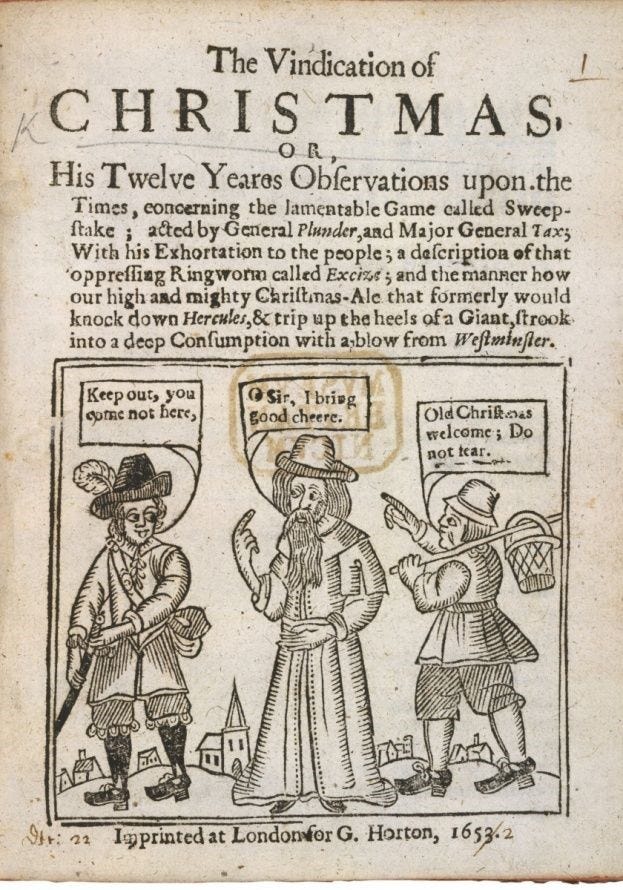

Christmas continued to be celebrated in England, merging ‘pagan’ festivities and traditions with Christian observances and iconography until the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 16th century, Calvinist Scots banned the ‘pagan’ excesses of Christmas in Scotland and the Puritans did the same in England a hundred years later. Due to there being no mention of Christmas in the bible, Oliver Cromwell’s administration banned any form of celebrating during the Twelve Days of Christmas, through an Act of Parliament in 1644. The Puritans did the same in America, particularly in New Plymouth, Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay. Massachusetts went to the extent of outlawing the celebration of Christmas in 1659.

For preventing disorders arising in several places within this jurisdiction, by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries, to the great dishonor of God and offence of others, it is therefore ordered by this Court and the authority thereof, that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon such accountants as aforesaid, every person so offending shall pay of every such offence five shillings, as a fine to the county. Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England. 1659.

In both Britain and the US, Christmas became a day of work and fasting until 1660 in England, when the monarchy was restored under King Charles II after popular unrest and street riots opposing the bans. The Puritan disdain for Christmas lasted a bit longer in the US, with Christmas gradually becoming universally accepted by 1840, and finally recognised as a national holiday in 1870.

The Victorian Christmas Revival

Christmas remained a quiet, religious observance until the mid-1800s when a confluence of Victorian-era romantic antiquarianism spread through the United Kingdom and the British colonies in Canada and America with the efforts of Queen Victoria, who imported German Christmas traditions for her German husband Prince Alfred, and the publication of several stories and poems that strongly influenced the Christmas zeitgeist. We will revisit Queen Victoria’s impact on the revival of Christmas in a future article about Yule and the Yule Tree.

In 1823 American poet Clement Clark Moore published his famous and still popular poem, The Night Before Christmas, which established the figure of Santa Claus in Christmas mythology. Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol in 1843, and American writer Washington Irving’s Old Christmas, a collection of Christmas stories was published in 1875, further cementing Christmas traditions into popular culture. The Victorian era also repositioned Christmas as a celebration of family centred on the indulgence of children and childhood and encouraged philanthropy amongst the middle classes.

Happy, happy Christmas, that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days; that can recall to the old man the pleasure of his youth; that can transport the sailor and the traveller, thousands of miles away, back to his own fireside and his quiet home! Charles Dickens (1812-1870) The Pickwick Papers.

The invention of the commercially produced Christmas cards in 1843 started a Christmas tradition that continues to this day, despite the advent of digital communication, and impacted on the popularity of Christmas symbols and icons.

I am collecting cards and postcards that have secular seasonal celebration-based themes. If you have any secular seasonal vintage postcards, from anywhere in the world that you don’t know what to do with, and you don’t want to throw them out, please consider sending them to me. Just drop me a note, send me an email or write something in the comment section and I’ll be in touch!

Although the revived Christmas echoed the old mid-Winter celebrations, it omitted many old customs in favour of what was available to most of the middle class of that era.

‘Instead of toast and ale, we content ourselves with sherry and chestnuts, and we must put up with coffee and fragrant tea, instead of the old Wassail-bowl.’ The boar’s head was replaced by ‘the roast beef of old England, a turkey or a goose,’ together with a plum pudding, all of which ornamented ‘the table of the peasant or artisan, for which he had during some previous weeks been preparing’ J.M Golby and Purdue. (2000). The Making of a Modern Christmas. Sutton Publishing, p.57.

This short 2:55 minute video from History Channel’s Bet You Didn’t Know, has a lot of information about the history of Christmas for those short on time.

In the next article, we’ll delve into the festive and delicious culinary customs of the winter solstice, Christmas and Yule. See you soon!