After one final heatwave to hurrah summer’s end, Autumn and cooler weather have finally arrived. Here in Australia, Autumn officially starts on 1 March though the First Peoples of our region consider late summer, Winyuwangga, to finish closer to the end of April. The landscape, fundamentally changed by colonisation, is now turning on its fiery Autumnal blush from introduced winter deciduous trees. Berry plants, fruit and nut trees, also introduced to this region with the spread of colonisation, are bursting with ripening fruit and edible mushrooms will soon flourish. I’m looking forward to rambles in the Autumn landscape, foraging the seasonal bounty.

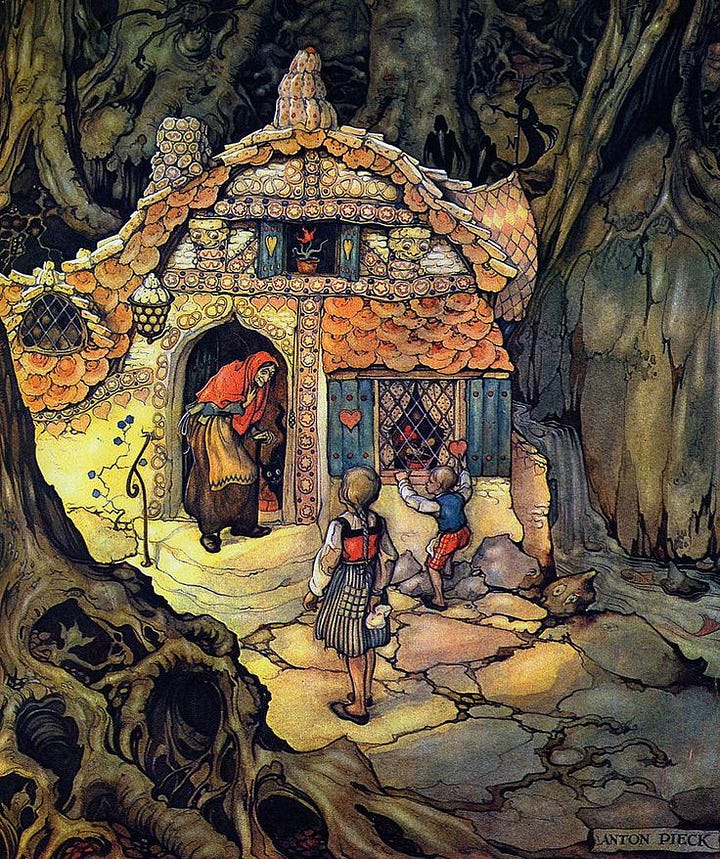

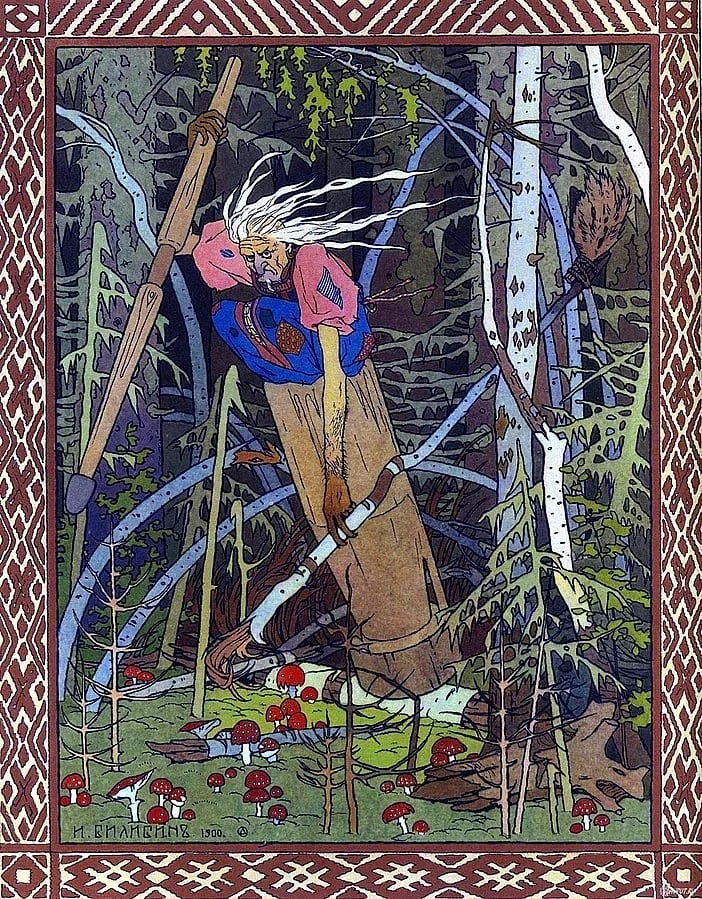

I adore foraging, especially on the edges of my town and pine forests at this time of year. There’s nothing as peaceful and enjoyable as gathering plump and sweet blackberries, tart crabapples, juicy wild plums, deep red haw berries and rose hips, and earthy mushrooms in a basket, under a clear Autumn sky, rugged-up against the cool breeze, with the warm sun on my back. There is such joy in finding, eating and sharing delicious sweet morsels with my children, or spotting toadstools in the forest and imagining Baba Yaga or the witch from Hansel and Gretel are nearby. It’s fun to feel the frisson of old fairytales and folktales, and otherworldly things drawing near.

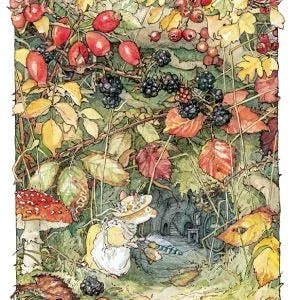

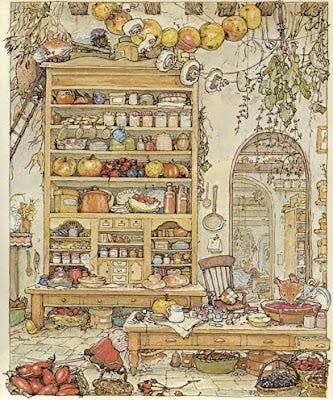

I also love revisiting the sweet and visually rich Autumnal world of Brambly Hedge’s Autumn Story, written and illustrated by Jill Barklem.

The video below features Autumn Story, an episode from the stop-motion animated TV series, The Enchanted World of Brambly Hedge, released in October 1997, based on the eight Brambly Hedge books by Jill Barklem.

Hedgerows are a particularly liminal space, filled with Autumnal bounty. In celebration of my favourite season, the season that feels most magical and enchanted, let’s explore the history and folklore of the hedgerows and their harvests.

Hedgerows

Hedgerows are liminal places, living fences of tangled wildness, in contrast to the ‘civilised’ and domesticated landscapes they often bound. They serve as property boundaries, field borders, livestock barriers, and wildlife havens and can be seen crisscrossing the countryside throughout the British Isles, part of the agricultural landscape for centuries. In Britain, their use can be traced back to the Bronze Age, gaining prominence during the Enclosure Acts of the 18th century when they were used to divide open fields and commons into individual plots.

Typically, hedgerows are composed of a variety of plants that provide nectar from flowers in Spring, shelter and shade in summer, and fruit (many edible but some poisonous) from late Summer to Autumn. They include shrubs like hawthorn, blackthorn and hazel, and trees such as crab apple and elder. The undergrowth might contain brambles, ferns, herbs and a carpet of wildflowers – each species contributing to a dense and diverse ecosystem.

Folklore is rich where hedgerows thrive. They are often associated with mythical creatures and tales of old. In folklore, hedgerows are often regarded as the veils between worlds, marking the boundaries between the civilized and the wild, the mundane and the magical. They are said to be inhabited by a variety of creatures, from fairies and spirits to witches and even dragons. In some tales, they are portals to other realms or times.

Hedge witches use the plants found in hedgerows for their medicinal and magical properties. These women were said to maintain the balance between humans and nature, using their knowledge of herbs to heal and protect. They were called wisewomen, healers, and henwives in their positive form, or witches in the perjorative form. In modern times, some people openly identify as a hedge witch and #hedgewitch is popular on social media.

In the colored fairy books of Andrew Lang (The Red Fairy Book, The Blue Fairy Book, etc.), there is a figure who has always intrigued me: the Hen Wife, related to the witch, the seer, and the herbalist, but different from them too: a distinct and potent archetype of her own, an enchanted figure beneath a humble white apron. We find her dispensing wisdom and magic in the folk tales of the British Isles and far beyond (all the way to Russia and China): a woman who is part of the community, not separate from it like the classic "witch in the woods"; a woman who is married, domesticated like her animal familiars, and yet conversant with women's mysteries, sexuality, and magic.

Terri Windling, Hen Wives, Spinsters, and Lolly Willowes.

Hedge Plant Lore

There are many folktales and folklore specific to each plant that frequently inhabit the hedgerow. Folklore about the richness of the hedgerow harvest and weather divination for the coming winter is also common throughout Europe. An old English saying describes this belief: Many haws, many snows or, Many haws, cold toes. 19th century English poet, John Clare, wrote a lovely poem about the joys of the Autumn season and one of the verses mentions this weather lore:

The Thorns and Briars, vermillion hue. Now full of Hips and Haws are seen; If village prophesies be true. They prove that Winter will be keen.

A verse from the 19th poem, Autumn by John Clare

Hawthorn

Hawthorn (Crataegus spp) forms the backbone of many hedgerows. We don’t often see formal hedgerows in Australia but hawthorn (and cottoneaster) are very common in our region, following lines of fencing along roadsides. Hawthorn is a particularly important plant in folklore and is considered a sacred plant in many European cultures. Across the British Isles and particularly in Ireland, hawthorn was considered home to the faeries, also called the Good People, Sidhe, or Aos Sí. Lone hawthorn trees in a field or by a spring were especially charmed and sacred. Even in this day and age, farmers are reluctant to bulldoze or cut these lone trees and roads have been re-routed to avoid causing any damage to the trees, and to avoid the ire of the Good People. The hawthorn tree was particularly important in the spring celebration of Beltane, where it was often referred to as the May Bush and you can find out more about this in the Wheel & Cross podcast and article, Episode 23 - Beltane (Earth): A-Maying, The May Bush and May Poles.

In late summer and early Autumn, the small haw berries ripen to bright red and though they are edible, they aren’t particularly palatable. Haw berries or haws are often used to make jams and jellies or dried and infused in herbal teas. Just be careful not to confuse it with cottoneaster berries, which are poisonous to people, dogs and livestock. In Western Herbal and Chinese Medicine the berries are used to help with cardiac issues such as irregular heartbeat, congestive heart failure, high blood pressure, and chest pain, as well as for digestive ailments. They are also used to help with emotional states related to heartbreak and loneliness.

Blackthorn

European folklore is rich with tales and symbolism surrounding the blackthorn tree, known scientifically as Prunus spinosa. This thorny shrub, native to Europe, plays a significant role in myths and legends across various cultures. In Celtic mythology, the blackthorn is often associated with dark aspects of magic and the otherworld. It is said to be a tree of ill omen, connected with the dark side of the year when days are short and nights are long.

The tree's hard wood was used to make cudgels and walking sticks, known as shillelaghs, which were also believed to possess magical power. The Cailleach was known to carry a staff made of blackthorn that she would strike against the ground to bring Winter to the land. Episode 2: Holle’s Day and the First Day of Winter explored the figure of the Cailleach and provides more information about her stories.

In some traditions, the blackthorn is also linked to protection. Its spiky thorns were thought to ward off evil, and it was often planted near homes for this purpose. The tree's fruit, sloes, are steeped in folklore as well. These sour berries are traditionally picked after the first frost, which is said to sweeten them, and are used to make sloe gin—a practice that continues to this day.

Elder

Elder trees (Sambucus spp) are also steeped in myth and their dark purple berries have been used for centuries to ward off evil spirits and heal ailments. According to English and Scandinavian legend, the elder tree was home to the Elder Mother, a spirit who watched over the forest. It was believed that before cutting down an elder tree, one must ask the Elder Mother for permission, lest they risk her wrath. A common phrase for woodsmen before cutting down an Elder tree was:

"Old girl, give me some of thy wood and I will give thee some of mine when I grow into a tree."

Charlotte Sophia Burne (2003) Handbook of Folklore, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7661-3058-6

In Scandinavia and Slavic countries, it was believed that the elder tree could drive out evil spirits. Danes also believed that standing under an elder on Midsummer's Eve allowed one to see the Elf-king and his host, which is similar to a Scottish tradition where it was said to happen on All Hallows Eve or Samhain. In England, it was believed that the elder tree could never be hit by lightning and that elder bark or twigs could protect their bearer from rheumatism. Farmers placed crosses made from elder on their cow-sheds and barns to protect their animals from evil.

In herbal medicine, elderberries are celebrated for their immune-boosting properties. They are packed with antioxidants and vitamins that can help fight colds and flu. A syrup made from these berries is a common remedy for respiratory infections and has been used for generations to promote health and wellbeing. Elderberry flowers can be made into a cordial for a refreshing drink but beware, all parts of the elder tree, including the berries and flowers, are poisonous and contain cyanogenic glycosides. Cooking the berries and flowers denatures their toxicity.

Crab Apple

Crab apple trees (Malus spp, particularly Malus Sylvestris) are the wild ancestors of the domestic apple and are found across Eurasia, along with regional folklore. The small, tart crab apple fruits are often associated with magic, healing and traditional herbal medicine. It is also the only ancient apple tree indigenous to Britain - the domestic apple was introduced to the British Isles by the Romans.

According to legend throughout Europe, crab apples were considered a symbol of love, fertility and marriage. To the Anglo-Saxons, crab apples had magical properties and were believed to banish evil and heal all ills. They were part of the "nine great herbs" charm, which is mentioned in the ancient Lacnunga manuscript. In Ireland, crab apples are considered sacred, used by the faerie folk as a gateway to travel between this world and the supernatural Otherworld. During Samhain, the origins for Halloween, crab apples were used in love divinations. In the Irish folktale of Cormac Mac Airt, a legendary High King of Ireland, a silver branch with golden apples from the Otherworld brings peace and healing to those who hear its music.

In Slavic regions crab apples were also associated with protection and fertility. It was common to plant a crab apple tree in celebration of a new birth, symbolizing a wish for a fruitful life and protection from evil spirits. Crab apples were used in love spells and charms. Young women would place crab apples under their pillows to dream of their future husbands or use them in various rituals to attract love and ensure a happy marriage.

Crab apples also hold a significant place in the history of brewing ale and cider. They are tart and tannic, making them less desirable for eating out of hand but excellent for fermentation. The high acidity and astringency of crab apples were used to add complexity and depth to both ale and cider, and its high level of tannins was used to preserve the beverage. Apple cider vinegar is also made with a mix of domestic and crab apples.

Crab apples are used medicinally as they are rich in vitamin C, which boosts immunity, improves skin health, and promotes wound healing. The presence of malic and tartaric acids in crab apples can also support liver health and improve overall metabolism. Additionally, they are a good source of pectin, a type of fiber that aids in digestion and helps regulate blood sugar levels. This makes them ideal for use as a base for jams and jellies, which preserve the fruit and concentrate its medicinal properties.

Blackberry

Blackberry brambles (Rubus fruticosus) dot the fields and paddocks throughout much of southern Australia. They were brought to Australia by British colonists and though their prolific fruit is a good source of food, their vigour and hardiness have caused serious adverse impacts on agriculture, tourism and native ecologies.

Blackberry has already cost around $100 million to control and in lost production. It quickly infests large areas; forms dense thickets that restrict stock access to waterways and access via fire trails; takes over pastures; is unpalatable to most livestock; reduces native habitat for plants and animals; fuels bushfires; provides shelter for rabbits and foxes, and; provides food for introduced species such as starlings, blackbirds and foxes

Blackberries are now considered a Weed of National Significance, requiring ongoing management practices and long term control. The NSW Department of Primary Industry a WeedWise profile for Blackberry with more information.

Although considered problematic in the Australian landscape, blackberries are an important and natural feature of European landscapes. In European folktales, blackberries are often seen as symbols of abundance and sometimes caution. According to folklore from the British Isles, fairies are said to guard blackberry bushes. Those who respect the plants and the faeries are rewarded with bountiful harvests. Conversely, picking berries after a certain date, most often Michaelmas on September 29, is said to invite misfortune, as it's believed that the fruit will be blighted by the devil.

This belief comes from a Christian folktale in which Archangel Michael defeated Archangel Lucifer and threw him out of Heaven into Hell. Lucifer, the Devil, landed on a patch of blackberries, causing him much pain. He cursed the blackberry fruit and spat (or peed in some tales) on them, causing the berries to blight. And so it is that berries should not be eaten from Michaelmas Day. Although this is a Christian tale, there is buried within it old wisdom to avoid eating blackberry fruit after the first frosts as they will likely be spoiled and tasteless. For those of us in the southern hemisphere, that date translates to March 29 and the first frosts of the season.

Blackberries were also said to have transformational powers. In Eastern European stories, blackberries often serve as magical agents that can change one's fate. A Polish folktale narrates the journey of a young man who, upon eating a mystical blackberry, gains the ability to understand animals' speech, leading him to uncover hidden treasures.

Although blackberries are considered a significant noxious weed in Australia, they also have some benefits in addition to their edible fruit. Their blossoms support pollinators in spring, their thick brambles provide food and shelter for native animals and birds such as bandicoots and blue wrens, their leaves are used in herbal medicines and they make an impenetrable landscape barrier in hedgerows.

The Value of Hedgerows

Hedgerows offer a multitude of benefits. They serve as vital wildlife corridors, supporting biodiversity by providing habitat and food for a variety of species. Additionally, they contribute to landscape stability, prevent soil erosion, and enhance water quality by filtering runoff. Their dense foliage also acts as a windbreak, protecting crops and reducing wind damage. They sequester carbon and also add aesthetic value to the countryside, preserving the character and history of rural landscapes in Britain.

Since 1945, however, hedgerows have been deteriorating and disappearing from the British landscape due to changes in countryside management. Projects are being established around the British Isles to re-establish and regenerate hedgerows. In Australia, native hedgerows are becoming popular and can provide all the benefits of the traditional hedgerow, including delicious edible berries.

As well as creating a haven for wildlife, native hedgerows can have a suite of other beneficial effects on the garden and the planet. They’re excellent screens to keep out road noise and certainly capture much more carbon than a barbed wire fence. They also act as barriers to desiccating summer winds and help to keep humidity in your garden, reducing the need to water frequently.

I hope you enjoy foraging this season’s bounty and maybe consider creating your own hedgerow for your garden. Next week we will explore the traditions, history and folklore of the apple harvest. In the meantime, I leave you with some wise words from Benjamin Franklin:

Love your Neighbour; yet don’t pull down your Hedge.

Share this post