Dear Readers,

Samhain draws ever closer here in the southern hemisphere, with Samhain Eve occurring on Wednesday next week. Pumpkins are hardening on the back verandah in preparation for their Jack-O-Lantern carving. Decorations will be brought out from their storage spaces after ANZAC Day on Friday, and photos of our ancestors and dearly departed will be lovingly displayed once again.

Next week will be so busy with kids’ sports and after-school activities that this year, we’re delaying our traditional Samhain dinner until Sunday next week. This gives us (me) time to bake the Barmbrack Soul Cakes, and prepare the pumpkin soup served with cheesy garlic bread and a seven-apple crumble for dessert. We’ll light candles, lay a place at our table and serve food to honour our dearly departed and those who are too ancient to remember but still precious and revered.

In this final article on Samhain, we will explore the iconic beings that symbolise Samhain: witches; black-coloured animals like cats, dogs, corvids (ravens and crows), bats and horses; and finally, creatures from the Otherworld who inhabit the darkness.

Enjoy!!

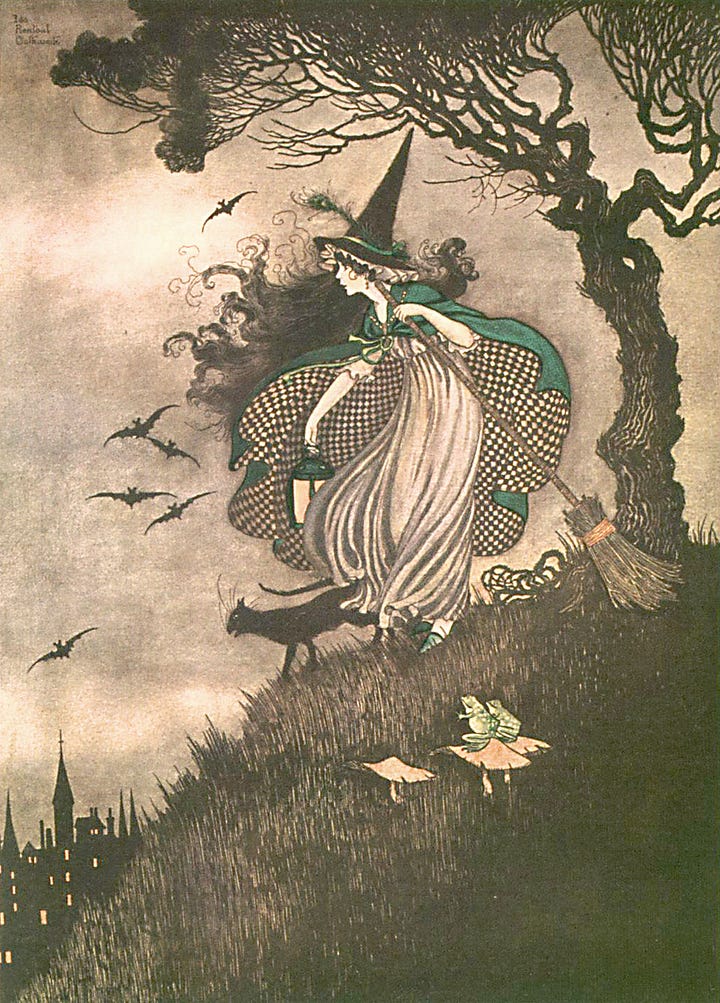

Witches

The history of witches is deeply intertwined with European cultures and folk practices. In pre-Christian times, witches were often revered as wise healers and practitioners of folk magic, wielding knowledge of herbs, potions, and rituals for the benefit of their communities. Some were occasionally sought out for more nefarious purposes, such as hexing or cursing. Most witches were women. Many lived on the outskirts of their communities or at the fringes of their societies, while others were important and respected community figures. Midwives tended to women during childbirth, and often provided perinatal assistance to women and their babies, or assisted women to end unwanted pregnancies. They commonly used herbs, rituals and spellwork in their practice and were often sought out for more than their midwifery skills.

Henwives were women who played a crucial role in rural communities, particularly in the British Isles. They were known for their expertise in raising poultry, but their role extended far beyond mere animal husbandry. Henwives were often seen as wise women who possessed knowledge of herbalism, healing, and midwifery. They were integral to the fabric of society, providing practical assistance and wisdom, and sometimes even delving into the mystical, offering guidance and foresight. Henwives are often present in folklore and fairy tales, particularly from the British Isles. Their social ties to their communities contrasts them with the archetype of the ‘witch in the woods’ who lives alone and away from ‘civilisation’. Terry Windling’s blog, Myth and Moor features an excellent article on henwives.

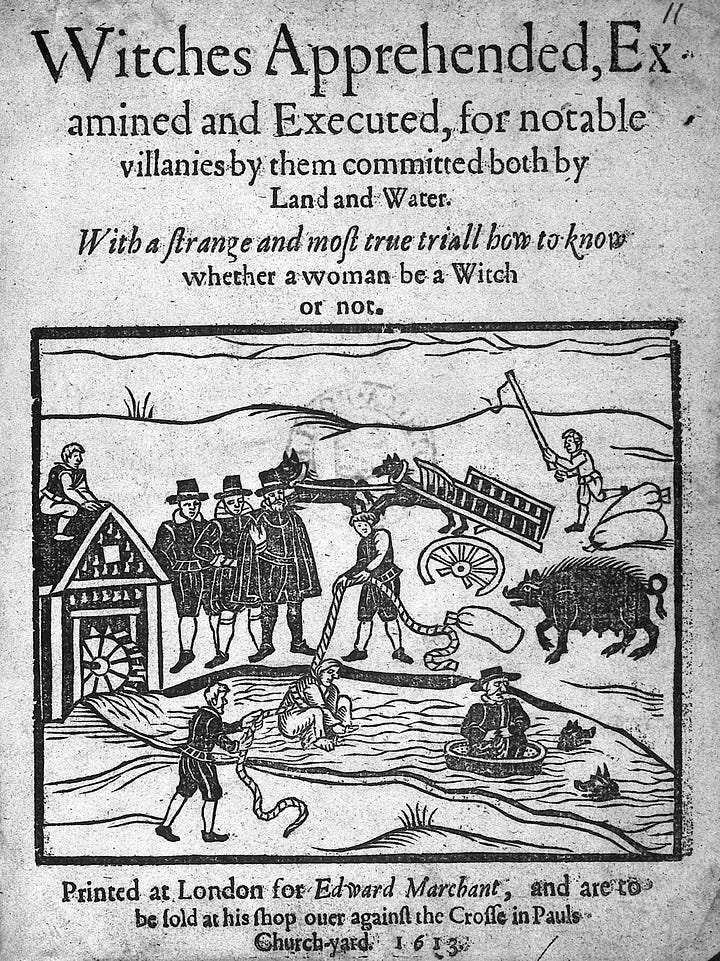

With the spread of Christianity, pagan traditions came to be viewed as heretical and were condemned by the Church. During the medieval period, the Church launched campaigns against witchcraft, portraying witches as servants of Satan who consorted with demons and engaged in malevolent acts such as casting curses, causing illness, and summoning storms. This demonisation of witches reached its peak during the witch hunts of the early modern period, particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries, when tens of thousands of people, primarily women, were accused of witchcraft and subjected to torture, sham trials, and execution during the infamous ‘witch hunts’.

Samhain, as a liminal time when the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead is thinnest, became associated with witchcraft and supernatural phenomena. It was believed that witches and other practitioners of magic could harness this liminal energy at Samhain to commune with spirits, perform divination, and work spells.

During the Christianization of Europe, many pagan beliefs and practices associated with Samhain were demonised and absorbed into the folklore surrounding witches. Samhain became conflated with the Christian holiday of All Saints' Day (November 1) and All Souls' Day (November 2), collectively known as Allhallowtide, and the association between witches and Samhain persisted. Samhain became a focal point for fear surrounding witchcraft rituals, both real and imagined.

Witches are iconic archetypes in myths, legends and fairytales across Europe:

Circe is a powerful enchantress in Greek mythology known for her herbal cunning and for turning Odysseus’ men into pigs.

Hecate is a Greek goddess associated with magic, witchcraft, crossroads, creatures of the night and the moon, often depicted with triple heads representing maiden, mother, and crone.

Trivia is the ancient Roman equivalent of Hecate.

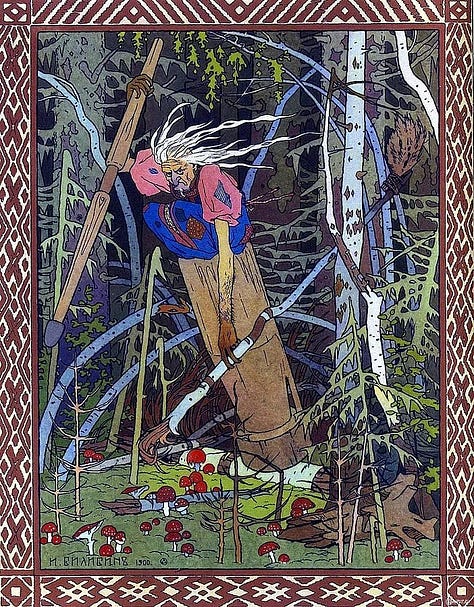

Baba Yaga is a fearsome witch from Slavic folklore, living in a hut that stands on chicken legs.

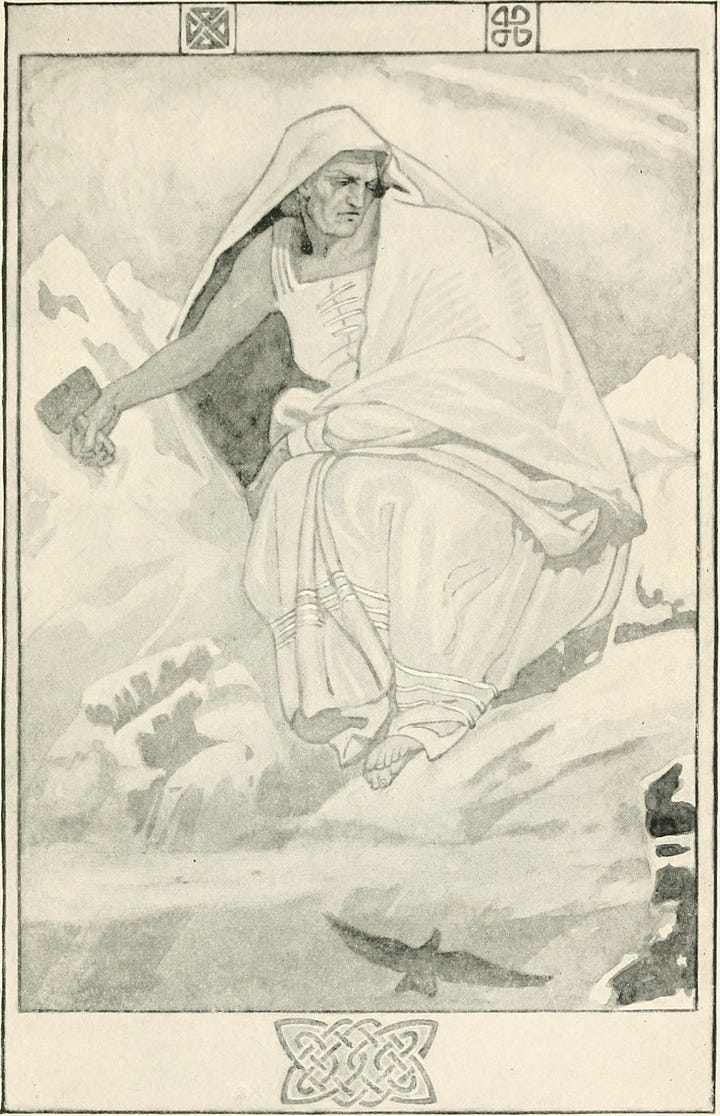

Cailleach is a hag or witch in Gaelic mythology, often depicted as an ancient and powerful figure associated with winter, storms, and the natural world.

La Befana is an Italian folklore character who delivers gifts to children on Epiphany Eve, and is often depicted as a witch.

Lilith is considered a witch in Jewish folklore and is associated with the night.

Vǫlur/Vǫlva, Seiðkonur/Seiðkona and Vísendakona are various names for witches in the Nordic languages.

Witches remain iconic figures in popular culture, and have been featured in art, literature and legislation: from ancient Greek and Roman laws banning the use of black or harm-causing magic, to the early Christian era with The Witch of Endor recorded in the book of Samuel written between 931 BC and 721 BC, to classical art and literature, as well as modern movies and books featuring witch characters. Disney has produced many animated movies featuring witches. The short (1 min) clip below features a tongue-in-cheek advertisement for ‘witches brew’ in the Disney/Pixar movie Brave.

In modern times, the image of the witch has undergone a transformation, with witches reclaiming their identity as practitioners of nature-based spirituality and proponents of feminist empowerment. Samhain remains an important holiday in contemporary pagan and Wiccan traditions, and Halloween, replete with witch costumes and decorations, has become a favourite celebration.

Hey-how for Hallowe’en!

A’ the witches tae be seen,

Some are black, an’ some green

Hey-How for Hallowe’en.

Traditional Scottish Verse

Creatures of Darkness

Black coloured animals such as cats, dogs, corvids (ravens and crows), bats and horses have been associated with Samhain and Halloween for many thousands of years.

Black Cats

There are few creatures as iconic during Samhain and Halloween as black cats. Black cats have long been associated with witchcraft and magic in European folklore. Sometimes, they were a symbol of good fortune. In Scottish folklore, black cats were considered lucky, and one arriving at a home signified prosperity. In other parts of the British Isles and most of the rest of Europe, a black cat crossing your path was considered unlucky, or even an omen of death. During the Middle Ages, they were believed to be witches' familiars, or supernatural entities that aided witches in performing spells and rituals. As a result, black cats were often feared and persecuted.

Black Dogs

Found in myths, legends and folktales throughout Europe, black dogs are also iconic figures of the liminal world. They were often called hellhounds, and were believed to be harbingers of doom, omens of death and guardians of the underworld. In ancient Greece, Cerebrus, a three-headed hound with a jet black coat, guarded the gates of Hades (the underworld) and prevented the dead from leaving. Ancient Celts believed black dogs acted as psychopomps, escorting newly deceased souls from Earth to the afterlife.

In Nordic and Germanic mythologies, mythical wild hunts featured rampaging hordes of gods or witches on horseback, often accompanied by baying black hounds. The sagas also tell of a large and blood-stained wolf or dog called Garmr, that guarded the gates of Hel.

The (12:03 mins) video below from Monstrum describes the origins of the hounds of hell.

In folklore across many Western and Eastern European cultures, the appearance of a black dog was often associated with specific locations such as crossroads, graveyards or even inside churches. Seeing a black dog was believed to foretell one’s demise. Large black dogs with fiery red eyes were sighted in places like Flanders, Belgium, called Oude Rode Ogen (‘Old Red Eyes’) or the ‘Beast of Flanders’. In Wallonia, southern Belgium, folktales mention a hellhound on a long chain thought to roam the fields at night, the Tchén al tchinne (‘Chained Hound’). In France, a black hound materialised in a church in Trier in 856 AD, bringing darkness with it as it padded up and down the aisles, as if it were looking for someone. It disappeared as suddenly as it appeared.

The Black Shuck, a ghostly black dog, is said to roam the East Anglian countryside. It is described as being unnaturally large, with glowing red or yellow eyes and is thought to be the incarnation of a hellhound. Stories of these black dogs or hellhounds inspired Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous Sherlock Holmes book, The Hound of the Baskervilles, first published in 1902.

The BBC clip (6:39 mins) below explains the origin and appearance of the Black Shuck.

Across England, church grims in the form of a large spectral dog with red eyes were believed to guard churchyards from thieves, vandals, witches, warlocks and even the Devil himself. In rituals that mirror pagan sacrifices from the distant past, when a new churchyard was opened, before the first person was buried within it, a black dog was sacrificed and buried in the north section of the churchyard to guard all newly interred souls against the Devil.

Corvids

Corvids (crows and ravens), with their glossy black feathers and their uncanny intelligence, are also connected to Samhain and Halloween. They are associated with death and the underworld because of their dark feathers and their habit of eating carrion and killing young and weak animals. They are despised by many farmers, as they can also cause great damage to agriculture and food production, especially in large numbers when they consume sown seeds and growing crops. Scarecrows were created to keep them out of fields.

Their habit of gathering near ancient burial mounds and sacred sites caused many to believe their presence indicated that spirits were nearby. Some European cultures also believed that crows and ravens were psychopomps, guiding souls to the afterlife. Corvid caws and movements were interpreted as omens, foretelling death or significant events. In some parts of Scotland, it is still believed that a crow resting on the roof of a house at Samhain is an ill omen portending death to someone in that household. Crows and ravens were often linked to witches and magic. The Norse god Odin had two crows, Huginn (thought) and Munnin (memory), who brought him news of all that happened in Midgard (the world of men). Crows and ravens were commonly considered to be fylgja (familiars) of Nordic vǫlva or seiðkona (witches).

Bats

Bats are also symbolic of Samhain and Halloween. They hunt and fly through the air at night, and although harmless to humans, their facial features can be frightening or eerie. They also carry diseases and are feared by many who believe they are associated with the Devil, evil spirits or witches. Pre-Christian Celts would light large bonfires at Samhain to ward off evil spirits, and these fires attracted insects. Bats, in turn, swooped around the flames, feasting on the bugs, and they were thought to be the embodied spirits of the returning dead. Folktales originating in Eastern Europe about blood-sucking bats and vampires shape-shifting into bats, spread throughout the rest of the continent and the British Isles through the long-standing tradition of scary tales told at Samhain and Halloween.

Black Horses

Similar to other black animals, the black horse is associated with symbols of death and the underworld in many European cultures. In ancient Greece, Hades, god of the underworld, rode a black horse. Similarly, Hel, Queen of the Nordic underworld realm of Helheim, rode a black horse named Hrimfaxi, which means ‘frost mane’. Hrimfaxi was said to bring the cold and darkness of Helheim with him as he travels through the night sky. The Nordic and Germanic gods and later witches were said to ride black horses with fiery eyes on their wild hunts.

In Celtic mythology, black horses were seen as harbingers of death and psychopomps, carrying souls to the afterlife. In Ireland, folklore tells of the Dullahan, who rides on the back of a flame-eyed black horse, holding his decapitated head.

The Irish púca is a goblin-like creature that can shape-shift into various animals, including horses, all of which have black fur and glowing red eyes. Similarly, kelpies are shape-shifting water spirits from Scottish folklore that commonly take the form of a striking black horse. They were said to crave human flesh and would lure unsuspecting humans onto their backs, before racing into the water and drowning their victims. In Christian folktales, the black horse is one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, representing famine and death.

In popular culture, Washington Irving’s famous short story, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, published in 1820, features a headless horseman, holding his Jack-O-Lantern head and riding a black horse with red glowing eyes. The terrifying Nazgûl, from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, rode on black horses. In the 2012 Dreamworks animated movie, The Rise of the Guardians, based on William Joyce’s The Guardians of Childhood book series, the antagonist, called Pitch Black, sends his nightmares, in the form of black and skeletal spectral horses with glowing eyes, to terrorise children’s dreams.

Otherworldly Beings

When the veil thins between this world and the otherworld, creatures from uncanny parts slip through and mischief is made: skeletons come to life, ghosts roam the earth, headless horsemen wheel and turn at crossroads, witches cast spells and work magic, the faeries (ghosts of the Tuatha de Dannan) are abroad on mysterious pilgrimage, screaming hordes and baying dogs echo in the deep night and many of these otherworldly beings crave the human soul or even human flesh! Each region across the globe has its own folktales of spooky and terrifying monsters from the other world. What wonderfully scary stories can you share at this liminal time of year?

I hope you enjoyed this series of four episodes on the spooky and pumpkin-filled season of Samhain/Halloween. Sadly, it is also the end of our seasonal year together as the new seasonal year begins on June 1, and I’ll be taking a break until then. The monthly South Lands Almanac will continue to be published, but I’m not sure yet what form this next seasonal year will take on Wheel & Cross.

I am very grateful to all of you who have taken the time to read or listen for the last two years. I would have researched and published these articles and episodes regardless of whether I had an audience, but it is so nice to have had you along for the journey. Thank you and see you again soon.

In the meantime, I offer you my favourite Irish blessing (altered to include people of all faith and of none):

May the road rise up to meet you.

May the wind always be at your back.

May the sun shine warm upon your face;

the rains fall soft upon your fields

and until we meet again,

May you be held gently upon this good earth.

If you’re interested, here’s a selection of mini-documentaries below from Monstrum.

Share this post