Please note: Australian First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) readers are advised that the following article contains images of deceased people.

I wrote last week about the possibility of celebrating Australia Day at Midsummer, not on a date but at a time of year, for example, the 4th Friday in January. This avoids the contention surrounding our current (and frankly sociopathic) date. It also honours Australia’s European ancestry, and our multicultural society, while also allowing our First Nations peoples and their supporters to participate in an inclusive and joyous celebration of our Nation. Today’s article is a bit more sombre than I usually like to write as I attempt to clarify why the date is so hurtful to and dismissive of the lived and historical experiences of our First Nations peoples, whose cultures, traditions, knowledge and humanity we should be proud to celebrate or acknowledge at the very least.

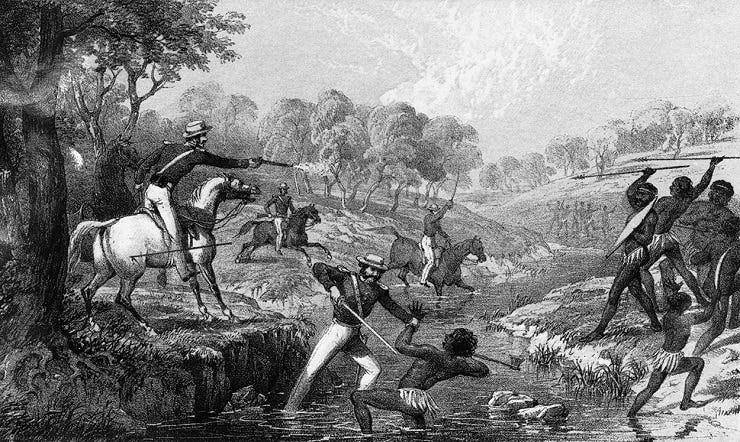

Australia’s national day, ‘Australia Day,’ is celebrated on January 26, with a public holiday, national awards, and citizenship ceremonies. The date commemorates the day that colonisers from the First Fleet, led by Arthur Phillip, first raised the British Flag at Sydney Cove. It ostensibly aims to bring the nation together in celebration but in reality, celebrating ‘Australia Day’ on this date causes great hurt and distress to First Nations peoples and their supporters, and has historically divided the nation since its inception. January 26 marks the start of the invasion of First Nations lands, the Frontier Wars, genocide, massacres, murders, rape, slavery, dispossession, stolen children, stolen land, stolen wages, cultural and environmental devastation, and other atrocities committed by British colonisers against Australia’s First Nations peoples.

Dehumanisation

Australia was colonised on the legal principle of terra nullius, meaning ‘land belonging to no one,’ which was interpreted as the complete absence of people, or people capable of land ownership. It wasn’t until the High Court of Australia’s Mabo decision in 1992 that terra nullius was overturned and First Nation’s connections and rights to land were recognised through Native Title.

From the outset of colonisation, First Nations people were considered to be sub-human and were treated as such socially and legally. They were enslaved or forced to work as indentured servants, their lands were taken, they were forced into missions and/or residential schools and they were considered wards of the state, not given full citizenship status until 1965 when prohibitions against voting in federal and state elections were lifted.

It was not until 1984 that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people gained full equality with other electors under the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 1983. This Act made enrolling to vote at federal elections compulsory for Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians Right to Vote, National Museum of Australia

Resistance

Although the narrative that First Nations peoples did not fight for their country or were passive victims of genocide and massacres during colonisation is widespread, the truth is that our First Nations fought hard against colonisation and actively engaged in ‘guerilla’ resistance against colonisers.

It’s becoming more and more apparent that First Nations resistance was organised and efficient. Co-author Ray Kerkhove’s How They Fought identified specific structures and tactics First Nations peoples’ employed during the Frontier Wars. Kerkhove analysed over 200 written reminiscences and hundreds of settler and First Nations accounts of skirmishes across Australia.

Kerkhove’s How They Fought suggests resistance was mostly a “slow drip” of constant harassment against the colonisers - but effective in halting settlement for many years in some regions. It identifies the complex tactics First Nations groups developed for raids, sieges, pitched battles and even their attempts to take over the pastoral industry of particular regions within the Northern Territory and South Australia.

Kerkhove’s research proposes First Nations’ forces had military-style training, ranking, “policing” patrols, defensive ‘bastions’, and intelligence networks. The research highlights the frequency and scale of inter-tribal meetings and partnerships during the Frontier Wars - for instance, in Tasmania, southern Queensland and western NSW. It finds traditional weapons were effective in causing many settler fatalities. The research also finds many new weapons, fire, steel, glass, guns and horses were adopted to halt the tide of settlement.

Why First Nations ‘ununiformed warriors’ qualify for the Australian War Memorial, by Ray Kerhove and Boe Skuthorpe-Spearim (2024)

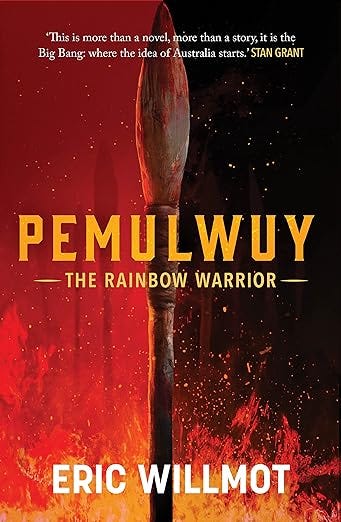

There are many examples of First Nations war leaders and resistance fighters who achieved fame amongst coloniser populations for the effectiveness of their tactics, such as Pemulwuy a Bidjigal man of the Eora nation (near Sydney). The Australian Frontier Conflicts website provides more examples and information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Warriors as well as conflict maps, timelines and other resources.

These Frontier Wars and resistance fighting against colonisation are finally being recognised by the Australian War Memorial.

Australia needs to understand the Frontier Wars were more than a sequence of massacres. Mob fought back. They had victories. First Nations peoples quickly recognised they were dealing with an existential threat, and created widespread resistance. This history is finally being written.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples emphasise the deep pain they feel when ANZAC [Day] rolls around each year, knowing Australia still does not formally recognise or acknowledge the blood, battles, lives and land that were lost.

Often this lack of recognition stems from limited knowledge of the sophistication of First Nations’ resistance. These “ununiformed” warriors had their own insignia and protocols. They acted with great valour and genius, against incredible odds. First Nations warriors should receive the same dignity we accord our ANZAC fallen.

Why First Nations ‘ununiformed warriors’ qualify for the Australian War Memorial, by Ray Kerhove and Boe Skuthorpe-Spearim (2024)

Although racism is not as overtly violent in modern times, systemic and social racism still impacts First Nations peoples and communities. Many First Nations people became activists fighting for equality and catalysing movements that led to changes to Commonwealth and State Laws. However, overt racism is still prevalent in Australian mainstream culture, and is fuelled annually by the racially motivated nationalistic fervour surrounding ‘Australia Day.’

There are many reasons why the 26 January and ‘Australia Day’ are controversial, painful and traumatic for First Nations people… First Nations people are being asked not only to celebrate Australia on the day colonisation began, but to celebrate a country which won’t even include them in its Constitution” (Glynn-McDonald, 2019).

‘Australia Day’ is considered a day of mourning and is known as Invasion Day by many First Nations peoples and their supporters.

The long history of ‘Australia Day’ protests

Australia’s First Nations peoples have been boycotting and protesting ‘Australia Day’ celebrations since its inception. ‘Australia Day’ was not celebrated by all Australian states and territories on January 26 until 1935, when it was met with controversy and protest. It did not become a public holiday until 1994.

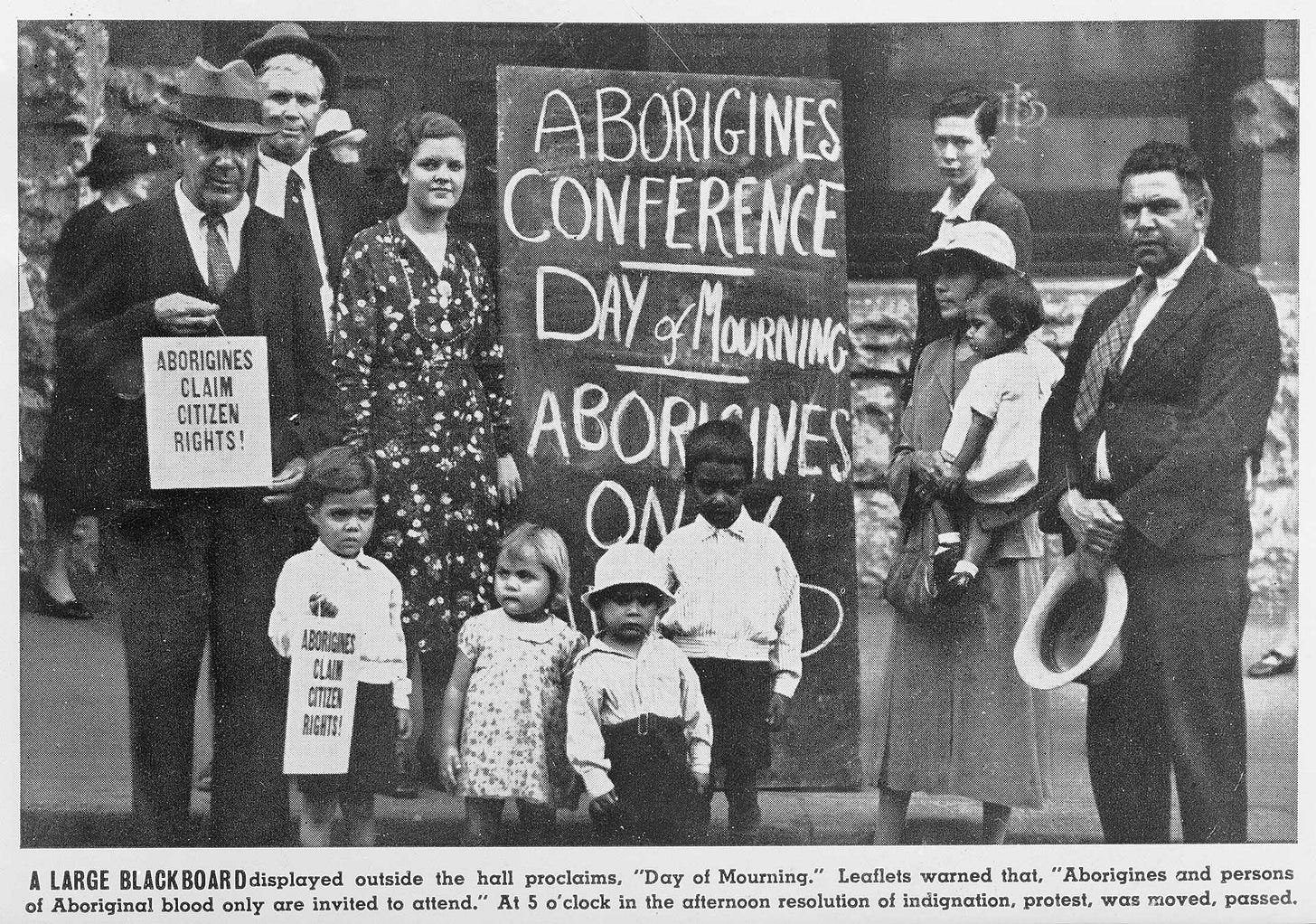

The 150th anniversary of colonisation was celebrated nationally in 1938, and First Nation’s organisations gathered in protest, declaring the first Day of Mourning:

WE, representing THE ABORIGINIES OF AUSTRALIA, assembled in conference at the Australian Hall, Sydney, on the 26th day of January, 1938, this being the 150th Anniversary of the Whiteman’s seizure of our country, HEREBY MAKE PROTEST against the callous treatment of our people by the whiteman during the past 150 years, AND WE APPEAL to the Australian nation of today to make new laws for the education and care of Aborigines, we ask for a new policy which will raise our people TO FULL CITIZEN STATUS and EQUALITY WITHIN THE COMMUNITY.

Resolution of indignation and protest moved and passed on 26 January 1938 (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2023)

In early January 1938, the Aborigines Progressive Association published a pamphlet titled ‘Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights’. Although First Nations peoples were eventually granted citizenship in 1965, the ABA’s words are still relevant:

The 26th of January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called “progress” in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country.

We, representing the Aborigines, now ask you, the reader of this appeal, to pause in the midst of your sesqui-centenary rejoicings and ask yourself honestly whether your “conscience” is clear in regard to the treatment of the Australian blacks by the Australian whites during the period of 150 years’ history which you celebrate?’

You are the New Australians, but we are the Old Australians. We have in our arteries the blood of the Original Australians, who have lived in this land for many thousands of years.

You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force. You have almost exterminated our people, but there are enough of us remaining to expose the humbug of your claim, as white Australians, to be a civilised, progressive, kindly and humane nation.

Aborigines Claim Citizenship Rights (1938), Aborigines Progressive Association.

Protests and marches have continued from that time forward. In more recent times, marches protesting ‘Australia Day’ and in support of First Nations have grown in size and number. Public discourse is starting to shift towards changing the date of Australia Day to one that does not commemorate colonisation or invasion. Some local councils have stopped holding citizenship ceremonies on this date (more info here). The national radio broadcaster (ABC)’s Triple J music channel stopped hosting its Hottest 100 on Australia Day in 2018 (more info here). Victoria has halted its Australia Day parade (more info here). Large companies and the Federal government announced that taking Australia Day as a public holiday was optional (more info here, here and here). This year Woolworths, Big W and Aldi have announced they would not be selling ‘Australia Day’ merchandise, despite public backlash from right-wing politicians and vandalism of stores (more info here and here). Although the concept of changing the date is gaining momentum (more info here and here), there is a lack of consensus on an alternative date and a growing movement to abolish the celebration of Australia Day altogether:

It is argued that without significant changes in key areas of justice relating to First Nations people, there is nothing to celebrate. These areas include social justice, legal restitution, widespread acknowledgement of Australia’s true history, treaty, self-determination (the power of self-governance) and constitutional recognition.

The movement highlights that the things commonly celebrated on Australia Day such as equality, freedom, opportunity, and our national identity are not reflective of the experience of First Nations people and indeed many other people in Australia. Advocates in this movement also describe how the nationalistic pride often celebrated around Australia Day is rooted in racist, colonial history, values and behaviours.

Invasion Day (Australia Day) by Glynn-McDonald (2019) in Common Ground.

Celebrating ‘Australia Day’ on 26 January is undoubtedly insensitive, hurtful, and harmful to many First Nations peoples and their supporters. It has been divisive since its inception and is opposed by a growing number of non-Indigenous Australians. In addition, many Australians are not interested in the historical or political aspects of the Australia Day public holiday. Let's change the date to the 4th Friday in January, aligning with Midsummer traditions from our European heritage, and around the world ensuring that our First Nations peoples are respected and included.

The video (2:55 mins) below is poignant and features First Nations (Aboriginal) people responding to ‘Australia Day.’

First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) viewers please note, that the music video below features UK rapper Cyclonious describing the invasion of Australia by colonisers, with images and voices of First Nations peoples who have died.

Resources

If you would like to read more, there are many good resources to choose from:

ARTICLES

Glynn-McDonald, R (2019) Invasion Day (Australia Day), Common Ground

Darian-Smith, Kate (2017). Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: a long history of celebration and contestation, The Conversation

Jones, B (2023) Australia Day hasn’t always been on January 26, but it has always been an issue, The Conversation

Carlson, B (2023) ‘Change the date’ debates about January 26 distract from the truth telling Australia needs to do, The Conversation

WEBSITES

National Museum of Australia

Australian Museum

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Islander Studies (AIATSIS)

Videos and Documentaries

Many documentaries explore the history and experiences of Australia’s First Nations people and the impact of colonisation. SBS Australia aired an excellent series of documentaries in 2017. They are available through SBS On Demand for those with an account. The first four in the series can be found on YouTube and are provided below.

First Australians (2017)

Episode 1: They Have Come to Stay - The 1788 arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney results in cautious friendships being formed between the First Australians and the British Empire. Yet within three years, relations sour as settlers spread out across the land.

Episode 2: Her Will to Survive - The land grab moves south to Tasmania. In an effort to protect real estate prices, Tasmanian Aboriginal people are removed from the island. The government enlists an Englishman for the job, who is helped by young Aboriginal woman Truganini.

Episode 3: Freedom for Our Lifetime - Aboriginal reserves are created but not welcomed; the threat of extinction hovers over the First Australians of Victoria; Wurundjeri clan leader Simon Wonga claims land on the banks of the Yarra River to farm.

Episode 4: There is No Other Law - White settlement significantly affects First Australians. Homicidal Constable Willshire brings mayhem to the Arrernte nation in Central Australia, and must be stopped by telegraph operator Frank Gillen when the authorities turn a blind eye.

Episode 5: An Unhealthy Government Experiment - European settlement spreads to Western Australia and is met with much conflict. More than 50,000 half-caste children are taken from their homes and placed in missions.

Episode 6: A Fair Deal for a Dark Race - Yorta Yorta man William Cooper forms the Australian Aborigines League in 1933 to campaign for equality. Successive campaigns help win constitutional rights in 1967.

Episode 7: We Are No Longer Shadows - Eddie Koiki Mabo battles for Australian law to recognise that his people own Murray Island, where they have lived for generations.

There will not be any articles published next week as I take a break to recover from surgery. Please stay tuned for an article the week after next, about Lughnasadh (The First Harvest).

Well said

Have you considered the very high likelihood that those opposing 26 Jan will just shift their protests to whatever day is chosen? This movement is not driven by good-faith concern for Aboriginal people's welfare but by culture war objectives.