South Lands Almanac - January 2025

Australian Capital Region

Wheel & Cross is proud to publish this monthly Almanac at the start of each month. It was created to observe and understand the cycle of seasons in the Australian Capital Region, through the lens of European agricultural knowledge and publicly available and openly shared knowledge of the traditional custodians of ‘Capital Country’, the Ngunnawal.

I acknowledge that the Ngambri people also claim custodianship of these lands. Unfortunately, I do not have any Ngambri cultural information regarding language, connection to Country or seasonal customs. This means I am unable to share anything relating to Ngambri culture but I am always keen to learn.

I pay my respects to all First Nations Elders, past and present and to all First Nations peoples from around Australia and the Torres Strait Islands who are the proud custodians of this Country we all love.

Contents

Ngunnawal season

Weather and Climate

December weather summary

Long-range forecast

January forecast

Natural emergencies

Star Gazing and Star Lore

Moon phases

Visible planets, meteors and solar movements

Western and First Nations ‘star lore’

Nature and Environment

Useful weeds

Native flora

Native fauna

In Season - seasonal crops, flowers and food

Important Dates

1 January - New Year’s Day

24 January - Midsummer (last Saturday in summer) - Triple J’s Hottest 100

26 January - Invasion Day (‘Australia Day’)

27 January - Invasion Day Public Holiday

Ngunnawal Season

Sources: Tyronne Bell, Ngunnawal Elder, Thunderstone Cultural Aboriginal Services

The Australian Capital Region is part of the Southern Tablelands. It has a cool temperate climate featuring warm to hot and dry summers and cold winters with heavy frosts and radiation fog. January marks the third month of the four month Ngunnawal season of Winyuwangga. Native edible grass, rush and wattle seeds are abundant during Winyuwangga. Bushfires are easily sparked by dry lighting, sparks from cooking fires or spontaneous combustion (usually hot composting material).

Before colonisation, the Australian Capital Region was less arid and contained less scrubland or open, denuded and degraded grasslands. Firestick management practices (cultural burning) shaped the local landscape for thousands of years, which was dominated by Yellow Box (Eucalyptus melliodora) Grassy Woodlands on the higher slopes, now listed as threatened, and Natural Temperate Grasslands on lower alluvial soil plains now listed as endangered. Large swathes of dry sclerophyll forest dominated the region with low-lying areas of swampland featuring ‘chain-of-ponds’ water bodies draining into rivers with riparian Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) grasslands.

Firestick cultural practices involved close monitoring of the landscape. Cool burns were lit in carefully selected areas during the cooler months, amongst other considerations, which regenerated the land and reduced the occurrence of highly flammable scrublands. These practices were stopped across Australia, including the Australian Capital Region with the onset of colonisation. The region is now dominated by weedy scrubland and degenerated forests and woodlands with high levels of combustible material that build up without regular cool burning. This, in addition to the changing climate, has resulted in increasingly dangerous, larger and hotter fires. Firestick culture has begun to re-emerge, with interest in cultural burns growing in the region.

Weather and Climate

Sources: Australian Bureau of Meteorology, WeatherZone.com.au, Timeanddate.com, Weather Spark

Weather Summary - December

Large rain events in the first week of December resulted in 101.8mm of rain, well above the average rainfall of 75.8mm, despite conditions drying in the second half of the month. Temperatures were also hotter than average, with average minimum of 12.7°C and maximum of 29.4°C compared to the average of 11.9°C to 27.2°C.

Max Temp - The average maximum temperature for December this year was 29.4°C, over 2°C warmer than the long-term average of 27.2°C but below the hottest December on record of 31.7°C in 2019. The highest maximum temperature was recorded on December 16 at 34.5°C, which was 6.2°C under the warmest maximum December temperature on record of 41.1°C on 21 December 2019.

Min Temp - The average minimum temperature for December this year was 12.7°C, warmer than the long-term average of 11.9°C and much warmer than the coldest November on record of 8.6°C in 2022. The lowest minimum temperature for the month was recorded on 24 December at 3.6°C, which was 3.3°C warmer than the coldest-ever temperature of 0.3°C on 6 December 2012.

Rainfall - It rained on 9.4 days in December with a total of 101.8mm, well above the December average of 9.4 days and 77.8mm of rain. The wettest December on record was in 2010 with 198.4mm of rain.

Long-Range Forecast (Update)

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology’s long-lange forcast for January to March predicts that most of the country, including the Australian Capital Region, is expected to receive higher than average rainfall. Daytime temperatures will be average for this region and time of year though the nighttime temperatures are expected to be warmer than average.

The latest outlook video (2:40 mins) from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology provides a forecast for January to March. It contains a weather summary for November rather than December, presumably because the numbers for December have not yet been ‘crunched’.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is likely to remain neutral. However, Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) are forecast to remain warmer than average, especially in the south east of the country. Warm oceans increase the amount of water and energy in our atmosphere, which increases the severity of storms and rainfall events.

Increasing sea temperatures on Australia’s east coast have caused the East Australian Current to extend further south where the Tasman Sea is warming at twice the global average. It is not known how this will specifically impact weather patterns but the Australian Bureau of Meteorology is predicting one of the hottest summers on record, with extreme weather events increasing.

January Forecast

The Australian Capital Region is expected to experience above-average rainfall throughout January. Daytime temperatures are expected to remain average for the month. However, as with most other areas of Australia, nighttime temperatures will be much warmer than normal, increasing the chance of heatwaves. The bushfire outlook for our region indicates that there is no increased risk forecast for this season but that may change as the landscape is drying out and if forcasted rain does not eventuate. There is an increased risk for flash flooding and severe weather events in January.

Averages for the Australian Capital Region in January are:

Maximum Temperature 30°C

Minimum Temperature 14.2°C

Rainfall 46.8mm and 8.1 days of rain

Natural Emergencies - Fires, Floods, Heatwaves and Storms

Extreme heat has caused more deaths in Australia than any other natural hazard and has major impacts on nature and the environment. Ensure that plans are in place to survive extreme heat events including redundancies for power outages as extreme heat can impact the electricity grid.

The statutory Bush Fire Danger Period for Rural Fire Districts began on 1 October. Fire Permits are required throughout most of NSW including the Goulburn-Mulwaree, Queanbeyan-Palerang, Snowy Monaro and Yass Valley regions of NSW, and in the Australian Capital Territory. Make sure you understand your fire risk, prepare your homes and properties for the fire season, have a bush fire survival plan and pay attention to Fire Danger Ratings for your area. Visit the NSW Rural Fire Service (NSW RFS) and ACT Emergency Services Agency (ACT ESA) websites for more information.

Increased storm activity and higher-than-average rainfall inundation events are likely to lead to increased chances of local flooding and storm damage. Prepare your homes for the storm season, prepare flood, and storm survival plans, and pay attention to severe weather warnings. Visit the NSW State Emergency Service (NSW SES) website for more information.

The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience and the National Emergency Management Agency have developed the Australian Warning System to “provide information and warnings during emergencies like bushfire, flood, storm, extreme heat and severe weather.” There are three warning levels:

Advice (Yellow) - An incident has started. There is no immediate danger. Stay up to date in case the situation changes.

Watch and Act (Orange) - There is a heightened level of threat. Conditions are changing and you need to start taking action now to protect you and your family.

Emergency Warning (Red) - An Emergency Warning is the highest level of warning. You may be in danger and need to take action immediately. Any delay now puts your life at risk.

The NSW Hazards Near Me app provides access to current information and notifications from emergency services about local emergencies. Be sure to download it and set your ‘Watch Zones’.

Star Gazing and Star Lore

Sources: Weather Spark, The Lighthouse - Macquarie University, SciTech, Australian Indigenous Astronomy, The Conversation

The Sun and the Auroras

The Earth’s perihelion occurs on January 4, when the Earth is closest to the Sun. It occurs annually in the first week of January, two weeks after the December solstice (21 December).

The Sun reached its solar maximum at the end of last year, and scientists predict that it will continue well into 2025. Solar maximum is a period of intense solar activity precedeing the Sun’s magnetic poles switching before moving toward a period of low activity in an 11 year cycle. During the solar maximum, large numbers of sun spots appear, solar irradiance (sunshine strength) grows by about 0.07% and solar flares are larger and more frequent. Solar flares can cause geomagnetic storms on Earth, which can disrupt Earth’s magnetic field, affecting power grids, radio signlas, communications systems, satellite operations and GPS navigation.1 It also produces the stunning auroras we have been seeing over the last several months, which are expected to continue for a few more months this year.2

This video (2:33 mins) from ABC Australia explains the solar maximum and auroras. It was produced in April 2023, when scientists were predicting the solar maximum would be reached in July 2025. However, the solar maximum arrived early and was officially reached in October 2024.

Lunar Phases

Tuesday, 7th - First Quarter Moon (waxing) - Rise 1:25pm E, Zenith 12:21am W

Tuesday, 14th - FULL MOON (Grain or Lugh’s Moon)* - Rise 8:55pm ENE, Zenith 12:58am N, Set 5:45am WNW

Wednesday, 22nd - Last Quarter Moon (waning) - Rise 12:02am ESE, Set 1:51pm WSW

Wednesday, 29th - New Moon - Rise 5:24am ESE, Set 8:20pm WSW

*The names of the full moons provided here generally correspond with names used in old English agricultural calendars and similar American Almanacs, although they have been re-arranged according to their appropriate season in the southern hemisphere. See Full Moon Names for the Southern Hemisphere for more information.

Stars, Planets and Meteors

Not all stars in the night sky are scientifically stars. True stars comprise the vast number of what we call ‘stars’. They appear to twinkle as their light comes from active suns in distant solar systems. The other celestial bodies we call ‘stars’ are planets in our solar system visible from Earth. They shine steadily in the night sky rather than twinkle as they steadily reflect the sun’s light, rather than producing their own light.

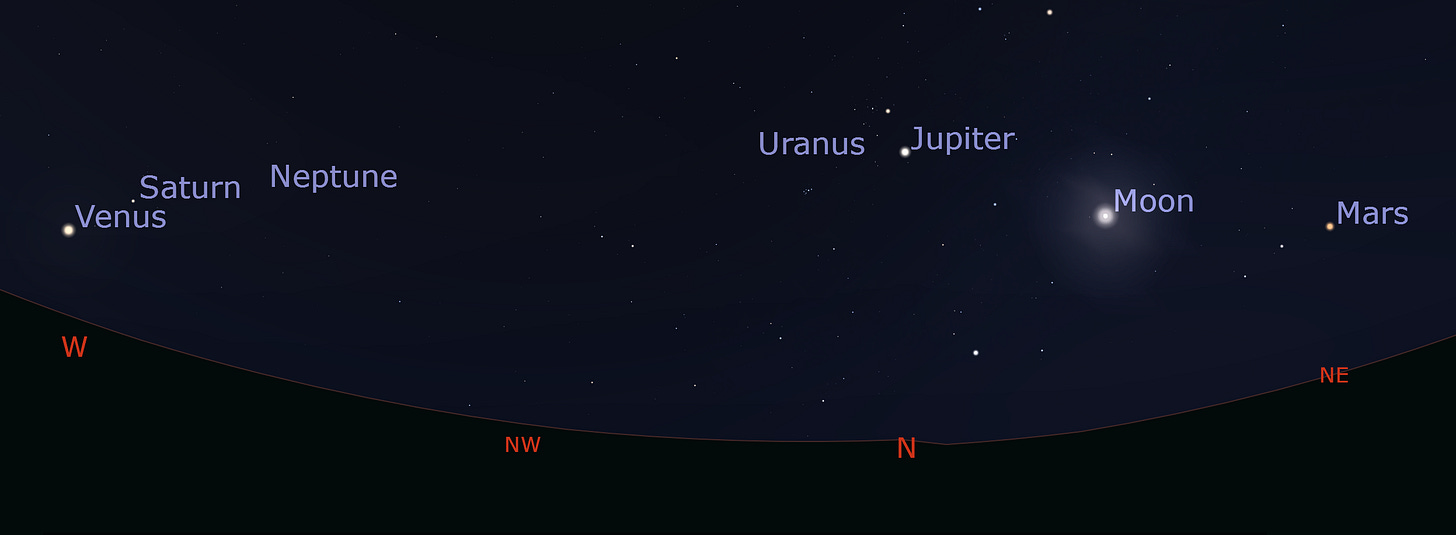

Venus, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Uranus and Neptune move into alignment on 25 January and can be seen together in the sky throughout the month after sunset in the western sky. By 9pm they will move to their zenith in the north-northwest. The moon will also visible in the alignment between the 2nd and 15th of January. A telescope will be needed to see Uranus and Neptune.

MERCURY - is visible above the eastern horizon an hour or so before sunrise for the first half of the month before the Sun’s glare makes it invisible for the rest of the month.

VENUS (also known as ‘The Evening Star’) - is visible all month accompanied by Saturn. They are closest to each other in the sky on 18 January and are within a handspan of eachother for the week on either side of the 18th. Both planets can be seen at sunset and will sink lower on the western horizon as the month progresses.

MARS - reaches opposition (is opposite to the Sun) on 16 January, meaning that the red planet rises as the Sun sets and will be visible all night. It is the best time to see the planet for the next couple of years. On 23 January, Mars can be observed near the star Pollux in the Gemini constellation.

JUPITER - the largest planet in our solar system continues to move slowly through Taurus in the north.

SATURN - is visible all month accompanied by Venus. They are closest to each other in the sky on 18 January and are within a handspan of eachother for the week on either side of the 18th. Both planets can be seen at sunset and will sink lower on the western horizon as the month progresses.

METEORS - Meteors from the Quadrantis meteor shower may be visible in the Australia on January 3 and 4 but their radiant (the area of origin) is below the northern horizon. This metoer shower is better seen in the northern hemisphere.

Constellation - Southern Cross

The Southern Cross, known as the Crux (Latin for cross) constellation by astronomers, is the smallest of the 88 official constellations, and one of the brightest and easiest to identify. It cannot be seen in the northern hemisphere north of 20 degrees latitude and is visible throughout the year from Sydney, south. The Southern Cross was once visible to ancient Greek astronomers before the Axial Precession caused by Earth’s rotational wobble (Chandler Wobble) meant that it disappeared from the Northern Hemisphere.3

The video (3:06 mins) below provides an excellent overview of the movement of the Earth through its axial precession.

January marks the Southern Cross’ nadir (lowest point) in the southern skies. It lies on its side in the southeast before rising in the sky and moving to its upright position in April. It keeps rising to its zenith in June while changing orientation to its side in the southwest. It then starts to sink and eventually, appears upside down in October.

Although the Southern Cross changes its orientation and position through the year, it can always be viewed year-round and is used to locate due south in conjunction with the ‘Pointer Stars’ Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri in the Sagittarius (Centaur) constellation. Ancient seafarers used the Southern Cross to navigate the southern oceans, and modern sailors still use it for navigation.

The Southern Cross is culturally important across many countries in the Southern Hemisphere. In addition to navigation, its position in the sky was commonly used to indicate seasonal and agricultural cycles. Some scholars believe that the Chakana (Andean Cross) icon, found carved in stone and depicted in textiles, pottery and other utensils throughout Latin America, represents the Southern Cross.4

It was an important constellation for the Māori of New Zealand:

There are different traditional interpretations of the Southern Cross in New Zealand, and it is known by at least eight different names in Māori. Tainui Māori saw it as an anchor, named Te Punga, of a great sky canoe, while to Wairarapa Māori it was Māhutonga – an aperture in Te Ikaroa (the Milky Way) through which storm winds escaped.5

The Southern Cross is important for many Australian First Nations.

The Bandjin (‘Saltwater’ people) from Hinchinbrook Island and Lucinda Point on the adjoining mainland of north Queensland, as well as Gould and Garden Islands and part of Dunk Island, believed that the Southern Cross represented the shovelnose ray Dhui Dhui. The story below was sourced from the Australian Indigenous Astronomy website, told by Russell Butler:

Long ago, two boys paddled out in a canoe south of Dunk Island (Coonangalbah) and dropped their stone anchor to fish. The elders had warned them not to fish on that sand spit because there was a big dangerous shovelnose ray (Dhui Dhui) that lived there. But the boys were defiant and fished there anyway. As they fished, the ray bit their line and started to tow them around in the canoe, but the boys wouldn’t let go of the line. It towed them around the ocean for a while before going down the Hinchinbrook channel. They disappeared into the horizon. By then, it was getting dark and everyone was worried about the boys. As the people looked south after sunset, they saw the Southern Cross rising, which was Dhui Dhui (the shovelnose ray), followed by the two Pointer stars (the two boys in their canoe).

Other Australian First Nations stories related to the Southern Cross were collated by Bathal, R. and Mason, T (2011):6

The Triangulum Australae, the Pointers and the Southern Cross are associated with Aboriginal family relationships and marriage traditions. Thus, the stars Alpha Trianguli and Beta Trianguli are the parents of Beta Centauri, while Alpha Crucis and Beta Crucis are the parents of Alpha Centauri. These relationships are significant as it is culturally important that marriages take place between the correct groups. The Southern Cross has many stories associated with it. In fishing communities the Southern Cross is seen as a stingray being chased by a shark (the Pointers). In other communities it is seen as the footprint of a wedge-tailed eagle or as Mirrabooka (a man who did good deeds on Earth), who when he died was placed in the sky by the Ancestor Spirits to look after his people.

Australia and New Zealand, as well as Papua New Guinea, Samoa and Brazil, prominently feature the Southern Cross on their respective flags.

Nature and the Environment

Most of the information provided about native seasonal flora and fauna is relevant to the cool climate region in Australia’s south, particularly the Australian Capital Region, and can be found in the book, ‘Ngunnawal Plant Use: A Traditional Aboriginal Plant Use Guide for the ACT region,’ and the ‘Ngunnawal Seasonal Calendar’ by Ngunawal Elder and traditional custodian, Tyronne Bell from Thunderstone Aboriginal Cultural Services.

Useful Weeds (Food/Medicine)

Wild Fennel (Foeniculum Vulgare) - Wild fennel is the same species as domesticated fennel althoug it rarely sets a bulb like the domesticated varieties. It is a herbaceous perennial plant with delicate, anise-scented and flavoured leaves. It is considered an invasive plant or weed as it grows vigourously in any soil type, including disturbed or marginal soils, and it produces large numbers of seeds. It can be seen in fields, abandonded or unkempt areas and along roadsides throughout the Australian Capital Region and is easily identified by its tall stalks, small, whispy leaves and bright yellow-coloured flower umbels.

All parts of wild fennel are edible, including stalks and stems, fronds, flowers, pollen, unripe and ripe seeds, and even the root. Fresh wild fennel fronds are used fresh or dried in pastas, soups, seafood and sauteed with vegetables. Fennel stems and bulbs need to be softened by cooking for 15 to 20 minutes and work well in soups, paella and pastas. It is commonly used in Indian, Middle Eastern, Greek and Italian cuisine and is one of the main ingredients in Absynthe.

Wild fennel is used medicinally for many kinds of digestive issues including bloating, gas, poor appetite, nausea and may relieve IBS symptoms. It may also encourage breast milk production and help alleviate collic in infants. Lightly crush a teaspoon of seeds in a mortar to crack the casing then add to boiling water. Allow the tea to rest for five minutes and serve it tepid.

Fronds are best harvested in spring, eaten fresh or preserved by drying of freezing. Seeds are easy to harvest in late summer and autumn. Collect the seed heads and shake them over a container. Pick out or thresh the chaff from the seeds, keep in a dry, cool place to dry before storing it in an airtight container. Avoid harvesting from roadsides and heavily polluted areas.

Flora

Prickly Currant Bush (Coprosma quadrifida) - Small and dense shrub found in damp and sheltered sites within woodlands, Eucalyptus forests and cool-temperate rainforests. Small and edible orange to red fruit begin ripening in January.

Appleberry (Billardiera scandens) - Climbing plant or sprawling ground cover that may grow as a small shrub in an open position. It can be found in coastal heath, schlerophyll forest and inland mallee habitats. It’s leaves are hairy and narrowly oval. It develops pendulous bell-shaped flowers in spring and summer, that develop into an oblong berry in January. The fruit is fleshy green and purple when immature, which are inedible unless roasted. The fruit is ripe and can be eaten raw when it is yellow and has fallen to the ground. Other common names include Apple Dumpling and Snotberry.

Cauliflower Bush (Cassinia longifolia) - Erect, aromatic and sticky shrub that grows in schlerophyll forest, woodland and heath on sandy or gravely soils. It has white cauliflower-like flower heads that bloom throughout summer. The Cauliflower Bush is a significant plant for Ngunnawal people, its leaves are highly fragrant and used to smoke and cleanse areas or spirits during ceremonies. The leaves can also be eaten and used as a sticky bandaid.

Grain Harvest

Source: Grainwise.com.au

The southern region winter grain crop harvest finishes in January: Barley, Canola, Cereal rye, Chickpeas, Faba beans, Field peas, Lentils, Lupins, Oats, Safflower, Triticale, Vetch, Wheat (according to type and weather).

The end of January and 1st of February marks the ancient Celtic celebration of Lughnassadh, First Harvest or Harvest of the Grains. More information about Lughassadh history and traditions will be published on Wheel & Cross at the end of the month.

Flowers

Sources: Meadow and Widler Farm, What Cut Flower is That

Flowers finishing this month: Carnations (Dianthus spp.)

Flowers starting this month: Aster (Aster spp.), Belladona Lily (Amaryllis belladona)

Flowers continuing this month: Agapanthus (Agapanthus spp.), Ageratum (Ageratum spp.), Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.), Baby’s Breath (Gypsophila paniculata), Bells of Ireland (Molucella laevis), Blazing Star (Liatris spicata), Canterbury Bells (Campanula medium), Chincherinshee (Ornithogalum spp.) Cock’s Comb (Celosia spp.), Cornflower (Centaurea spp.), Cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus spp.), Dahlias (Dahlia hybrids), Delphinium/Larkspur (Delphinium elatum), Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea), Gladioli (Gladiolus hybrids), Hollyhocks (Alcea and Alcathaea spp.), Hydrangea (Hydrangea spp.), Lavender - English (Lavender augustifolia), Lavender - French (Lavendar dentata), Lillies (Lily hybrids), Lisianthus (Eustoma spp.), Marigold (Tegetes erecta), Peruvian Lily (Alstromeria aurantiaca), Pincusion (Scabiosa caucasica), Roses (Rosa spp.), Sea Holly (Eryngium spp.), Smokebush (Cotinus spp.), Statice (Limonium spp.), Stocks (Matthiola incana), Sunflower (Helianthus annus), Zinnia (Zinnia spp.)

Kitchen Garden

Source: Food Tree

Herbs - Basil, bay, chives, coriander, dill, mint, oregano, parsley, rosemary, sage, thyme

Vegetables - Capsicum, celery, chilli, cucumber, celery, eggplant, kale, lettuce (cos, iceberg), onion (brown, red and white), pak choy, pumpkin (butternut), salad greens, spinach, spring onion, silverbeet, sweet corn, sweet potato, zucchini,

Fruit - Blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, red and black currents, cherries (peak season), nectarines (peak in January and February), peaches (peak in January and February), plums, grapes (white, red and black), oranges (Valencia), limes, melons (rockmelon, watermelon, honeydew)

Geoscience Australia. (2023). Space Weather. Australian Government (access 3 January 2025). https://www.ga.gov.au/education/natural-hazards/space-weather

Fazekas, A. (2024). 9 must-see night sky events to look forward to in 2025. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/2025-astronomy-night-sky-events

Maggy Wassilieff, 'Southern Cross - A national icon', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/southern-cross/page-1 (accessed 2 January 2025)

Ekberg Toscano, F. (2023). Living among gods – The Capacocha children : A hermeneutic analysis of the Chakana philosophy (Dissertation). Retrieved from https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-505145

Maggy Wassilieff. 'Southern Cross - A national icon', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/southern-cross/page-1 (accessed 2 January 2025)

Bhathal, R. and Mason, T. (2011). Aboriginal astronomical sites, landscapes and paintings. Astronomy & Geophysics, Vol. 52(4), pp. 4.12–4.16.

Such a wealth of information as always - fascinating to read! Thank you for pulling it all together like this. I love reading through.

Thank you Genevieve, such wonderful information and stories