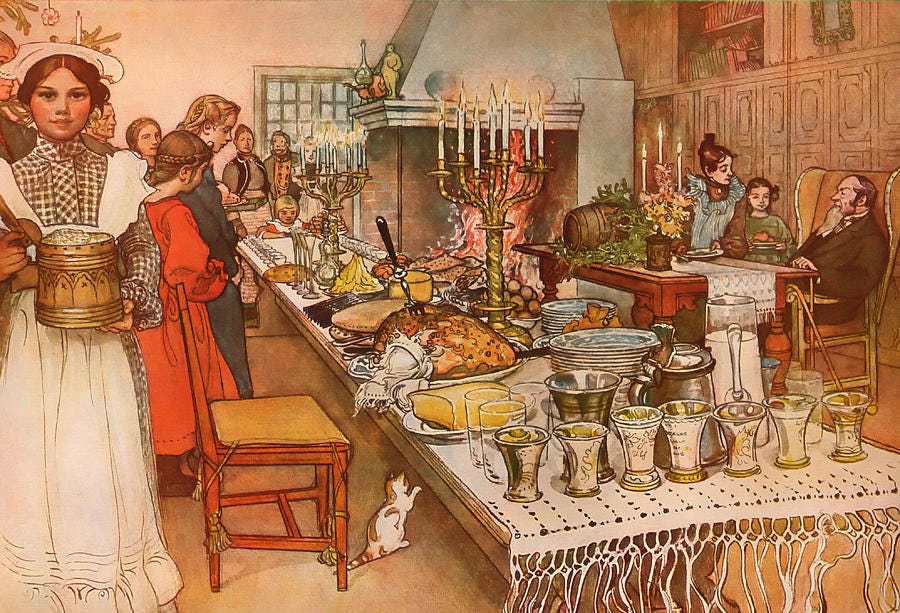

The tradition of feasting at the winter solstice is rooted in the customs and beliefs of the ancient Celts, Romans, and Germanic peoples. As we learned in a previous article on the Origins of Christmas, this tradition was discouraged amongst the poor and servile classes in England and in France by the Catholic church. However, the church struggled to stamp out many of the pagan customs surrounding the celebration of Christmas. By the Middle Ages, Christmas was a twelve-day extravaganza of feasting and revelry. It started on the morning of December 25, after the month-long fast of Advent, and culminated on January 5 with Twelfth Night, which we will explore in a later article. During this time, wealthy lords were expected to give their serfs twelve days off from labour and provide them with a festive meal. Royalty and the wealthy upper class gorged themselves for twelve days with elaborate meals, rich food and plenty of alcoholic drinks. The servants and serfs had to make do with pies, offal and ale.

Niall Edworthy states, in his book The Curious World of Christmas (2008) that:

During the Middle Ages, the tables of the rich were filled with “sumptuous displays of foods throughout the twelve days of Christmas. Goose was a common dish and the bird was often given a shiny, golden appearance by basting it in a mixture of butter and the highly coveted and expensive spice saffron. Pork or wild boar often formed the pièce de resistance of the Christmas feast, and the roasts were carried into the dining halls amid great fanfare with lemons stuffed into the beasts mouths”… In contrast, the medieval rich gave the poor a Christmas treat of deer innards, called ‘umbles,’ which were made into pies… the origin of the term ‘humble pie’ (p. 19).

After the Puritan-led bans on Christmas celebrations, the Victorian revival of Christmas allowed the growing middle class to indulge in more truncated versions of the Medieval and upper-class Christmas excesses by incorporating more commonly available and affordable meats and other foods to grace their festive tables.

There is so much to share about Christmas and Yule food traditions that I had to break this topic into two articles. In this first article, we will explore some of the more popular and well-known culinary delights of the Christmas, Yule, and winter solstice feasts, starting with the stars of the festive main meal: roast boar/pig, duck, goose, and turkey. Part two explores the sweet and delicious world of Christmas cake and plum pudding, gingerbread and spice cookies, the Yule log cake, oranges, and chestnuts. We’ll also revisit mulled wine, glögg and gluhwein, and explore the origins of eggnog, and rum toddies. Enjoy!

PS: The article on wassailing, carolling and the Mari Lwyd has been pushed to Friday.

The main course for many festive Christmas and Yule meals across Europe features roasted meats of some description, particularly roast boar/pig, duck, goose, turkey, and the ubiquitous roast beef. These were often accompanied by roasted vegetables and other side dishes and trimmings specific to each region. The most symbolic and much-anticipated part of the Christmas or Yule feast remains the roast meat, which is still presented with fanfare, even if the old processions and rituals are considered passé.

Roast Boar/Pig

Boars were endemic in the UK until the 13th Century when they became extinct due to hunting. According to the UK’s Wildwood Trust:

A revival was attempted in the 1700’s but these didn’t re-establish due to further persecution. In the 20th century, wild boar were introduced as a livestock animal, farmed for their meat. However following escapes from both these farms and other captive populations, populations of wild boar seemed to re-establish themselves in the 1980s-1990s.

Boars are dangerous to hunt and thus a much sought-after quarry. They are difficult to kill due to their solid body build, thick skin, and large head protected by an extremely strong skull. Boars can run fast, move quickly, and are good swimmers. They are also aggressive and strong animals with sharp tusks that protrude from their mouths. Stories of Kings and important legendary figures who are killed, maimed or injured by boars are common in European history and folklore.

An old Yule custom of the Germanic and Nordic people involved the public display and ritual of bringing in a boar’s head to the Yule feast held in the Great Hall. The short documentary (7:17 mins) below, from the History Channel’s Secrets of the Vikings, gives some insight into what Nordic feasting would have looked like.

The boar was considered a sacrifice to Freya the Nordic goddess of love, magic, sex, battle and death, and her brother Freyr, god of kingship, fertility, peace, prosperity, fair weather, and good harvest. In Norse mythology, Freya was often depicted riding a giant boar called Hildisvíni into battle. Hildisvíni, meaning battle swine, symbolises Freya’s power, bravery, and warlike aspects.

Freyr, on the other hand, was given a magical boar as a gift by the dwarf Brokkr, who also made Thor’s famous hammer, Mjölnir. This boar was called Gullinbursti, which meant Gold Mane or Golden Bristles, on account of its bristles being fashioned from gold, which were so bright that they lit up the sky as if it were day, even in the middle of the night. Freyr is sometimes described as riding across the heavens on the back of Gullinbursti, an obvious correlation with the rebirth of the sun at the winter solstice.

Then Brokkr brought forward his gifts: ... to Freyr he gave the boar, saying that it could run through air and water better than any horse, and it could never become so dark with night or gloom of the Murky Regions that there should not be sufficient light where he went, such was the glow from its mane and bristles. Snorri Sturluson. Prose Edda. c 1220.

The Celts also considered the boar to be a sacred and mythical creature, embodying both ferocity and fertility. One prominent figure in Celtic mythology linked to the boar is King Arthur, who in several stories, pursues the enchanted boar Twrch Trwyth, said to be a cursed king, sometimes with the help of his men and his hound, Cavell. Another tale from the King Arthur cycles featuring rich descriptions of the great hunt for Twrch Trwyth is the Welsh romance prose Culhwch and Olwen. The short 2:25 minute film by Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority tells the story of brave warrior Culhwch’s quest for his beautiful bride Olwen on the wild and rugged Preseli Hills.

The tradition of the boar’s head is also connected to pre-industrial agricultural cycles, where pigs were traditionally slaughtered and their meat preserved through the months of November and December, in time for the Christmas feasting.

At this point in the year pigs were consuming the last of the forest's free pig feed: acorns and beechnuts. Small farmers either had to find more feed, let the pigs go hungry, or slaughter them. Source: The Free Dictionary

Regardless of the origin, the tradition of bringing in the hog spread throughout Western Europe and became a common feature of Christmas celebrations for the wealthy ‘upper class’ and royalty.

Medieval Christmas festivities were celebrated with elaborate feasts, performances and games, throughout the season. One such Yuletide tradition was the Roasted Boar’s Head Feast, those with the means would have a boar’s head pickled, stuffed with forcemeat, roasted and then gilded with gold leaf, served on a platter with a fruit (orange/apple) in it’s mouth surrounded by herbs, delivered with a performance of musicians and entertainers creating a grand ceremony as it was presented to the head of the household. King Richard III Visitor Centre. Medieval Christmas: The Boars Head Festival

Although the Puritan Christmas bans were lifted in the 1600s, the boar’s head traditions disappeared for the most part, replaced by quieter customs and more affordable or available meats. However, the Boar’s Head Feast is still celebrated at Christmas by some old English and American institutions, such as at Oxford University’s Queen’s College, where the tradition is known as the Boar’s Heady Gaudy. The decorated boar’s head is displayed on a platter and paraded around the dining room, accompanied by a procession headed by a solo singer and followed by the college choir signing the Boar’s Head Carol.

The video below (2:04 mins) features the Randolph Singers, singing the Boar’s Head Carol with the lyrics and a translation of the Latin chorus at the end.

The Christmas Bird (Turkey, Duck, and Goose)

Roast goose and duck have a long history as a traditional dish for Christmas and Yule. They were used to grace the festive tables of rich and poor throughout Europe. Duck is still the most popular Christmas meat for the Danes, while goose is still popular in France and England, although these days, many European countries, like their North American cousins, enjoy turkey at Christmas.

In the Middle Ages, particularly during the reign of Henry VIII, royalty and the wealthy upper classes liked to display their wealth at Christmas by serving rare and exotic birds for Christmas feasts, such as swan, peacock, and the newly introduced turkey. Goose and duck were also served. Poultry, particularly duck and goose, were a popular choice for the Christmas feasts of the less wealthy as these birds were readily available and relatively affordable during the winter months.

Turkey

Turkeys are native to North America. They were first brought to Europe in the 1500s by the Spanish, from flocks of turkeys that had been domesticated for thousands of years by Aztecs in Mexico. Before establishing their own flocks on English soil, the English bought their turkeys from Turkish traders, thus their commonly accepted English names, while the French call turkey dinde, short for poulet d’inde (chicken of India), as Columbus initially thought he had landed in India when he first arrived in the Americas. English landowner and trader, William Strickland, imported the first flocks of turkeys for farming in 1526, for which he was granted a coat of arms, which included a depiction of a “turkey cock in his pride proper”.

Turkey soon became synonymous with Christmas as they became more commonly available in England. By the Victorian era, the growing middle class (white-collar workers) preferred to purchase turkeys, while duck and goose were preferred by the poorer working class (blue-collar workers).

‘A Christmas dinner, with the middle classes of this Empire, would scarcely be a Christmas dinner without its turkey, and we can hardly imagine and object of greater envy than is presented by a respected portly pater familias carving, at the season devoted to good cheer and genial charity, his own fat turkey and carving it well’. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, Isabella Beeton (1861).

Turkey drives became a common site in the regions around London, particularly in Norfolk and Suffolk. From as early as August, farmers would walk with flocks of up to 1,000 turkeys towards the London markets. This often took up to three months as apparently, turkeys tend to stroll and farmers needed to ensure the birds didn’t lose too much weight on their journey. The long walk to London was hard on the turkey’s feet so farmers protected them by making little leather boots, wrapping the turkey’s feet in rags or coating their feet in tar. After they reached London, they were fattened again for a short time before being dispatched in time for the Christmas markets.

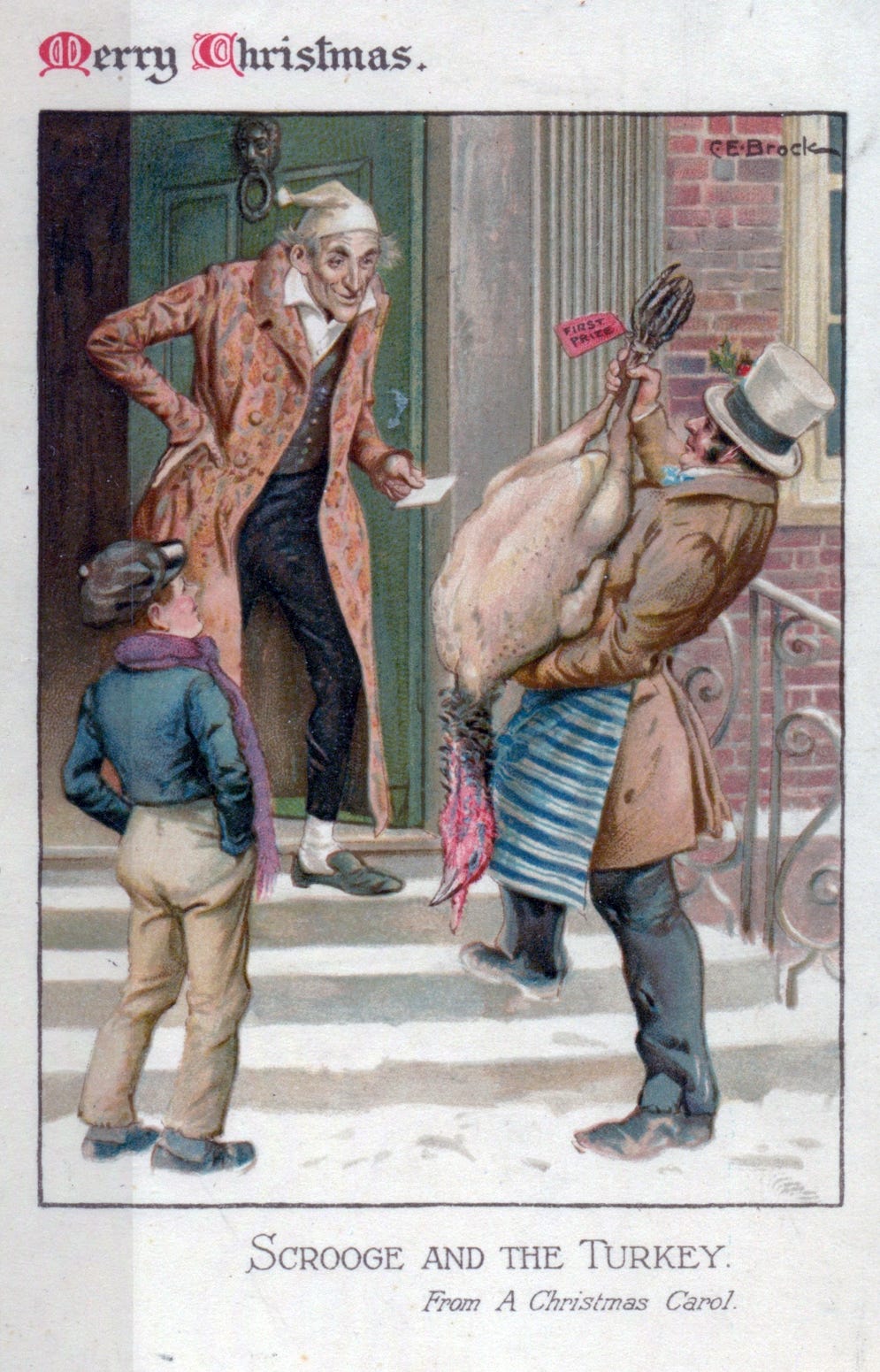

Charles Dickens helped to popularise the Christmas turkey in his novella A Christmas Carol, when a transfigured Ebenezer Scrooge buys a Christmas turkey for the poor Cratchit family.

“An intelligent boy!” said Scrooge. “A remarkable boy! Do you know whether they’ve sold the prize Turkey that was hanging up there?—Not the little prize Turkey: the big one?”…. “I’ll send it to Bob Cratchit’s!” whispered Scrooge, rubbing his hands, and splitting with a laugh. “He sha’n’t know who sends it. It’s twice the size of Tiny Tim.” A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens (1843).

Goose

During the Middle Ages, goose was a popular choice for festive meals due to its availability, rich flavour, and as a symbol of abundance and good fortune. They were an affordable indulgence for the Victorian-era working class and even the poor. As Christmas approached, geese were particularly prized as a centrepiece for the holiday feast for serfs and the working poor.

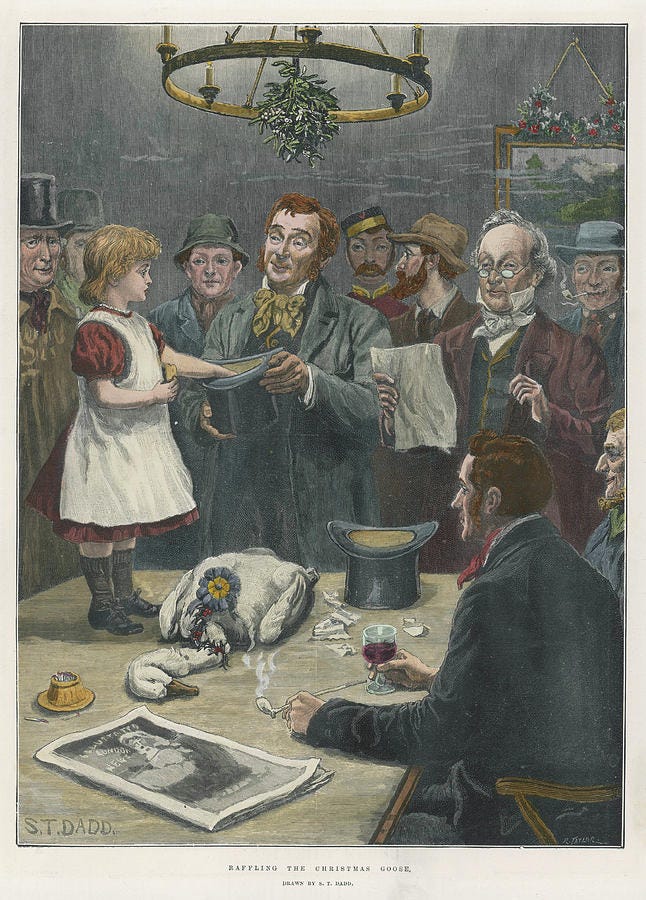

In some parts of Europe, the tradition of goose clubs or Christmas goose clubs evolved, particularly in England and Scotland during the 18th and 19th centuries. The purpose of the goose club was to pool resources and ensure that each member of the club could enjoy a festive meal centred around a roast goose for Christmas. Participants would contribute a small sum of money into a collective fund on a weekly or monthly basis throughout the year. The accumulated funds would then be used to purchase geese for each club member.

The geese were commonly bought in bulk from local farmers or markets. Typically, a designated goose club day was determined, often a few days before Christmas or Yule, when the geese would be distributed to the club members.

When the big day finally arrived, everyone who had paid in would congregate at the pub to claim their Christmas goose. To make it fair, all the names would be put into a hat. One goose would be held up and a name would be drawn. And, be it fat or scrawny, if your name was drawn, that’s the goose you got. At home the goose would be cleaned, prepared, and probably filled with sage and onion stuffing. Since most houses didn’t have ovens, all those geese would be taken to the bakers for roasting. Then on Christmas morning, everyone went to collect their dinner from the bakery. CuriousRambler.com

The distribution of geese from the goose club was often accompanied by celebrations, feasting, and merriment. These clubs provided an opportunity for people to come together, and strengthen community bonds during the holiday season, before the more private and family-centred Christmas Day celebration.

The tradition of goose clubs gradually declined with the changing socio-economic landscape and the shift towards more individualised celebrations. Turkey became a status symbol for the Victorian middle classes, where they were considered a luxury reserved for the Christmas season. However, after the 1950s, turkey became much more affordable due to improved farming methods, and their large size meant that families were able to host large gatherings. The Christmas goose thus gave way to the more popular turkey in modern times.

I have already mentioned my personal tradition of Beef Wellington to celebrate the winter solstice, but for my celebration of Yule at midwinter, I love to serve party guests roast pork and crackling with roasted vegetables. This year, I will try my hand at roast duck for the first time and I’ll keep you posted.

What are your favourite main meals for the festive season? I would love to hear your stories about the food you love to eat at Christmas and the fond memories that go with them. Please leave a comment or send me a message with your stories.

Stay tuned for Part 2 tomorrow, where we will explore the delicious and sweet world of Christmas desserts and treats. Until then… Cheers!!