The Origins of Yule

The celebration of Yule is a widespread tradition across Northern Europe, most likely originating from Proto-Indo-European traditions, before the bronze age and over 7,000 years ago. The word Yule or Jól in Old Norse is actually plural, meaning parties or festivities and refers to a period of around 12 days, encompassing several Yule celebrations that took place between the winter solstice and the period referred to as midwinter, which was most likely the first full moon after the solstice. Thus midwinter did not have a set date in Germanic calendars, rather it followed the lunar calendar cycles.

The name for midwinter in Old Norse was Jólablót. While Jóla refers to Yule, the term blót means blood and is the root word for the English blood, the German blut, and of course blod in the Scandinavian languages and in this context it refers to ritual sacrifice. The sacrifice of animals (and in some stories, humans) during winter is a significant seasonal observance in agricultural societies for several reasons. For Germanic peoples, the Jólablót was an important ritual ceremony to honour and appease Nordic Gods such as Thor. It was also an important aspect of animal husbandry, where sacrificing the least healthy animals ensured that the remaining healthiest animals would have enough food to weather the winter season. It was also important to ensure that meat was available for the Yule feasts, which served a social bonding as well as a religious function.

The Yule Log

The tradition of the Yule log can be traced back to ancient pagan rituals that were practised by various cultures in Europe, including the Slavs, Celts, and Germanic tribes. One of the earliest recorded references to the Yule log comes from Norse mythology. In the Norse tradition, the trunk of an oak tree was cut down and brought inside at the winter solstice. It was burnt for twelve days or until after midwinter, in honour of the god Thor, who was the god of war, thunder and lightning. The Norse called this log the Yule log or Jólablót (Yule sacrifice), which was believed to have protective and purifying properties, and its ashes were often scattered over the fields to ensure a fertile harvest in the coming year. Charcoal from the Jólablót was also kept under beds to protect from lightning.

As Christianity spread throughout Europe, many pagan customs and traditions were assimilated into Christian celebrations to facilitate the conversion of the population. The Yule log tradition was no exception. The symbolism of the Yule log was adapted to fit the Christian narrative, associating it with the birth of Jesus Christ and his role as the "Light of the World."

German Yule Log Traditions

This extract from Scandinavian Christmas Traditions provides a good overview of the German Yule Log traditions:

In Hesse and Westphalia, for instance, it was the custom on Christmas Eve or Day to lay a large block of wood on the fire and, as soon as it was charred a little, to take it off and preserve it. When a storm threatened, it was kindled again as a protection against lightning. It was called the Christbrand. In Thuringia a Christklotz (Christ log) is put on the fire before people go to bed, so that it may burn all through the night. Its remains are kept to protect the house from fire and ill-luck. In parts of Thuringia and in Mecklenburg, Pomerania, East Prussia, Saxony, and Bohemia, the fire is kept up all night on Christmas or New Year's Eve, and the ashes are used to rid cattle of vermin and protect plants and fruit-trees from insects, while in the country between the Sieg and Lahn the powdered ashes of an oaken log are strewn during the Thirteen Nights on the fields, to increase their fertility.

The tradition of the Christmas tree evolved in Germany from the Yule log tradition, which we will delve into in the next article.

English Yule Log Traditions

In Celtic traditions, the Yule log was seen as a sacred symbol representing the divine masculine energy and the sun. In England, an oak log was often used, while birch logs were preferred in Scotland. The logs were decorated with evergreen branches, holly, and ivy, which symbolised the eternal nature of life and the promise of new growth in the midst of winter. The Yule Log was called Yule Clog in the northeast of England, the Yule Block in the Midlands and West Country, Gule Block in Lincolnshire and in Cornwall, Stock in the Mock. In Wales, the Yule log is called Boncyff Nadolig or Blocyn y Gwyliau, meaning the Christmas Log or the Festival Block. In Scotland, it’s called Yeel Carline, meaning the Christmas Old Wife, while in Ireland it’s called Bloc na Nollag, meaning the Christmas Block.

The English West Country, particularly around Devon and Somerset, have a folk custom similar to the Yule log called the ashen faggot1. This Christmas Eve tradition is still celebrated and involves burning a large bundle of ash tree sticks in a hearth fire. The ashen faggot is usually bound with nine green lengths of ash called withies, preferably all from the same tree. Those watching must sing Carols and toast it with a drink every time a withie bursts. In some traditions, unmarried women would each choose a withie and the first one whose withie snapped would be married the following year.

In pubs around the region, bets were placed on the length of time until the last withie burst, with proceeds going to charity. Once the last withie burst, one or all of the sticks would be saved, to be placed in the centre of the following year’s ashen faggot. It was believed that any household that did not burn the ashen faggot would face years of bad luck and in some places, it was believed that burning the ashen faggot would protect the household from evil spirits, and later the Devil.

Come Bring the Noise

Come, bring, with a noise, My merry, merry boys, The Christmas Log to the firing: While my good Dame she Bids ye all be free, And drink to your hearts’ desiring. With the last year's Brand Light the new Block, and For good success in his spending, On your psaltries play, That sweet luck may Come while the log is a-teending Robert Herrick - clergyman and poet (1591-1674)

From there being an ever-burning fire, it has come to be that the fire must not be allowed to be extinguished on the last day of the old year, so that the old year's fire may last into the new year. In Lanarkshire it is considered unlucky to give out a light to any one on the morning of the new year, and therefore if the house-fire has been allowed to become extinguished recourse must be had to the embers of the village pile [for on New Year's Eve a great public bonfire is made]. In some places the self-extinction of the yule-log at Christmas is portentous of evil. Laurence Gomme - folklorist (1853-1916)

France

There are many traditions involving the Yule log throughout France. In Provence, the Yule Log is called le calingaou. On Christmas Eve the calingaou was traditionally brought inside while the family sang carols. It was then blessed (splashed) with wine and thrown on the fire. Charcoal from the log was kept as a remedy for various ills.

In some parts of France such as in Orne, the log is called the tréfoir de Noël and was traditionally burnt every evening over the twelve nights of Christmas. Its charcoal was either placed under the bed to protect from lightning; used in medicine for people and animals; or to help cows calf by mixing it in their fodder; or thrown into the soil to keep grain crops healthy.

In Périgord, the remaining unburnt parts of the log were fashioned into or added to a plough as it was believed to make seed prosper. It was also believed to help poultry thrive if added to their food over the twelve days of Christmas. In Brittany, the Yule Log was called tison and was also used as protection against lightning or its ashes were sprinkled into wells to keep the water clean.

When traditional hearths began to disappear from French homes and were replaced by wood-burning stoves, the burning of the Yule log was replaced by the sweet and much more tasty bûche de Noël (Yule Log cake), which you can read about in a previous article, Join the Feast Part 2: Sweets and Treats.

Italy

In Italy, the Yule Log tradition is called the Ceppo and was first recorded in the 11th century, although the tradition has far older pre-Christian roots. Christmas in Tuscany was once called the Festa di Ceppo (Feast of the Log). In the Tuscan village of Gorfigliano the tradition of Natelecci is celebrated on Christmas Eve, in which the tall trunk of a chestnut tree is mounted on most of the prominent hills around the village and piled high with juniper branches. At nightfall, the juniper branches are set alight and the bonfires flame into huge torches, while the village’s church bells ring out.

More commonly throughout Italy, a large log was brought into family homes and laid in their hearth on a bed of juniper. Lead by the head of the household, everyone would sing Ave Maria del Ceppo and the children danced, while the log was blessed with offerings of wine and coins before being set alight. In some places, blindfolded children would beat the Ceppo with sticks or pincers.

Similar to the Yule Log traditions of other European countries, the Ceppo was believed to bring good luck. Misfortune, mistakes and bad choices were burned in the Ceppo’s flames, wiping the slate clean for the New Year. A bit of the Ceppo was kept in the house to start next year’s log and to protect the house from fire and lightning. Ashes were placed in wells to keep the water flowing, and at the roots of fruit trees and vines to help them bear good harvests. However, it was considered an ill omen if the fire went out before the end of the night, as it heralded tragedy for the family in the coming year. If the flames cast someone’s shadow without a head, it was an even worse omen, as that person would supposedly die within the year.

In some regions of Italy, the Ceppo evolved into tiered shelves in the shape of a tree, known as the Tree of Light. The bottom shelf displayed the family’s treasured Presepio (creche or Nativity scene) and the remaining shelves displayed greenery, fruits, nuts and presents. The top of the Ceppo was usually adorned with an Angel or star.

Spain

Most Spanish Yule Log traditions are similar to those we’ve already encountered except for one amusing tradition from the Catalonian region, the Tió de Nadal. The modern Tió (Spanish for Uncle) is a hollow log about 30cm long that stands on two legs with a smiling face painted on its higher end, often wearing a red cap. From the Christian Feast of the Immaculate Conception on December 8 until Christmas Eve, children are tasked with taking care of the Tió by keeping it warm with a blanket and feeding it every day with offerings of fruit, vegetables and drink.

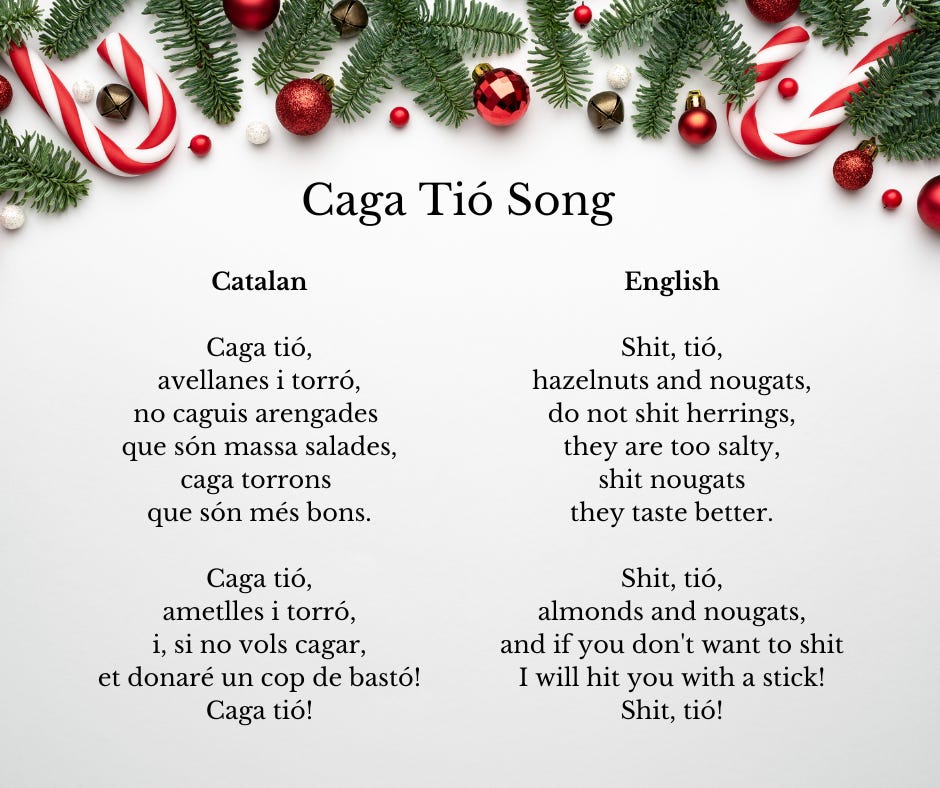

On Christmas Eve, the children are sent into another room, usually the kitchen, while the adults fill the log with small gifts and lollies. The children are then allowed back into the lounge room where the Tió is usually located, and proceed to beat the log with sticks while singing a special song, asking the Tió to poop presents and treats. One person puts their hand under the blanket and takes a treat before the beating and the singing starts again. The presents and treats are communal and enjoyed by the entire family, while the bigger and individual gifts are given on January 6, the day of Epiphany. The Tió is popularly called Caga Tió, which means ‘poo log’ or ‘shitting log’.

This short (1:34 mins) video describes the history and tradition of the Caga Tió de Nadal.

Eastern Europe

Many Slavic countries share similar beliefs and celebrate similar Yule Log traditions. In Serbia, Croatia and Montenegro, the badnjak log, which was considered to be a person or representation of the ancestors, was cut from young oak trees on the morning of January 6 (Christmas Eve in the Julian calendar). Splinters from the tree felling were taken home and placed where prosperity was most desired, such as beehives, in the hen-roost, or in the dairy room. The badnjak stump was blessed with grain, bread and wine or rakia (fruit brandy) and the log was brought back to the house, leant on the house near the front door and decorated according to local custom. In the evening it was ceremonially brought into the home and burned in the hearth.

It was customary for the polaznik, the first person to visit the family on Christmas Day,2 to strike the badnjak repeatedly to make as many sparks as possible in order to bring good fortune and joy to the household. Some regions believe that no family members should fall asleep before the log is split or burned through by the fire lest they will die without warning in the coming year. The splitting of the log by the fire was celebrated with wine and toasting. After the log was split by fire, the thinner end was kept in the fire to continue burning while the thicker end was taken out and used according to local customs, such as making crosses from the wood and placing the crosses under eaves, on the fields, in the meadows, vineyards, orchards, and apiaries.

The celebration of the badjnak began as a family custom and became a more public celebration, held in military barracks and eventually churches and royal palaces. Although most Serbs, Croats and Montenegrins no longer have hearths to burn large logs, they maintain the tradition of the badjnak by mounting twigs of oak with brown leaves still attached, to a place of significance in their households.

Yule Candles

The Yule log tradition in Scandinavian countries was eventually supplemented or replaced by a large candle that is lit on Yule Eve and kept burning throughout the holiday festivities. The lighting of the Yule candle is often done as a family ritual. It is believed to bring light, protection, and blessings to the home during the dark winter months. The candle is placed in a prominent location, such as a window or a central spot in the living room, where it can be seen and enjoyed by all.

In some Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden and Norway, it is common for families to have a special candleholder called a julstake or julestake to hold the Yule candle(s). The julstake is typically made of wood or metal and often has decorative elements like stars or angels. Alternatively, candles are placed on a decorated wreath.

The Yule candle is also associated with certain customs and superstitions. It was believed that if the candle burns brightly and steadily, it signified good luck and a prosperous year ahead. However, if the flame flickered or went out, it was considered a sign of impending misfortune. To prevent this, some people placed a coin under the candle or practice other rituals to ensure its uninterrupted burning. These days, the Yule candles are often electric, to avoid distinctly unfestive house fires (and bad luck from flickering flames).

If you can’t cut down a whole tree and burn it indoors in a giant hearth, why not decorate your own Yule log or make an ashen faggot for your fireplace or fire pit? If these options aren’t possible, light some Yule candles or turn on some electric candles this winter to celebrate an ancient Yule tradition that still resonates with meaning, and enjoy the hyggelig atmosphere of the season.

Next week we’ll continue our exploration of Yule traditions with the origins of the Yule tree.

Faggot is the term for a bundle of sticks bound together

The polaznik is someone chosen by the family, usually a young male, to be the first visitor to that family’s house, similar to the first-footing custom of New Year’s Day in the British Isles.