The merriment of the Yule season has come to a close for this year. The decorations were packed away on Monday and the last of the Yule marzipan was eaten (by me, as no one else in my household likes marzipan). After a week of sleet and wind, Monday evening was beautifully still and clear, the full moon rising as dusk deepened to night — a perfect backdrop to our short but sweet wassail of the orchard trees in our backyard.

Leftover mulled wine from our Yule party was reheated, poured into my favourite bowl and offered to each of our nine fruit trees, along with a hearty ‘Wassail.’ Then a slice of stale bread soaked in the mulled wine was hung at the top of each freshly pruned tree as a ‘toast’ or offering to the birds. Finally, the fir boughs and oak branchlets that decked the halls of my home for the Yule season, were burned in the fire pit as we enjoyed the warmth against the cold, crisp night and watched the moon rise.

As the month and season of Yule comes to a close, there’s one final aspect of European Christmas and Yule traditions to explore. Two small birds, the robin and the wren, have ancient and important connections with the seasonal winter folklore of Europe. Let’s dive into the folktales, traditions and history of these two little birds with big stories.

The robin and the wren are inextricably linked to the turning of the seasons in Celtic folklore. One widespread Celtic folktale tells of a battle between the new year and the old year. In order for the new year to be born, the robin, symbolising the new year, must kill his father, the wren who symbolises the old year. The wren’s blood splashes on the robin as he dies, giving the robin his red breast. This story reveals a strong connection to the turning seasons and stems from the birds’ seasonal behaviours. Whereas the wren is commonly seen and heard during the spring and summer months in Europe, virtually disappearing during winter, the robin is one of the only birds to be seen and heard in wintertime.

The relationship between these two birds has been memorialised in several English nursery rhymes depicting Cock Robin as a courting male and Jenny Wren as his feminine conquest.

Robin Redbreast Courts Jenny Wren

An English Children’s Nursery Rhyme

’Twas on a merry time,

When Jenny Wren was young,

So neatly as she danced,

And so sweetly as she sung,

Robin Redbreast lost his heart,

He was a gallant bird,

He doffed his cap to Jenny Wren,

Requesting to be heard.

“My dearest Jenny Wren,

If you will but be mine,

You shall dine on cherry pie,

And drink nice currant wine;

I’ll dress you like a gold-finch,

Or like a peacock gay,

So if you’ll have me, Jenny, dear,

Let us appoint the day.”

Jenny blushed behind her fan

And thus declared her mind -

“So let it be to-morrow, Rob,

I’ll take your offer kind;

Cherry pie is very good,

And so is currant wine,

But I will wear my plain brown gown,

And never dress too fine.”

Robin Redbreast got up early,

All at the break of day,

He flew to Jenny Wren’s house,

And sang a roundelay;

He sang of Robin Redbreast,

And pretty Jenny Wren,

And when he came unto the end,

He then began again.

The Robin

The friendly and cheerful robin (Erithacus rubecula) has been associated with winter for a very long time as it is one of the only birds to sing during the cold months after the summer breeding season in Europe. Hearing the robin’s song on Christmas Day was considered lucky and there are folk beliefs that a wish made on the first robin’s song heard on New Years day would come true. Similarly, if you saw a robin on New Year’s Day and made a wish before the robin flew away then your wish would come true.

As we saw at the beginning of this article, the robin was associated with the turn of the year in pre-Christian Celtic traditions, getting its redbreast from the blood of its father who was sacrificed to ensure the sun and the light returned.

The story of how the robin got his red breast was later adapted by Christians so that the blood staining the robin’s throat and neck became the blood of Jesus after the robin removed a thorn from the crown of thorns piercing Jesus’ head while he hung crucified. Another Christian legend accounts for the robin’s red breast:

It is said that when Mary was giving birth to baby Jesus in the stable, she noticed that the fire that they had lit to stay warm and comfortable was in danger of going out. Suddenly, a small brown bird appeared and started flapping its wings in front of the fire, causing it to roar back to life. However, as the bird flew around tending to the fire, a stray ember made its way towards the bird, scorching its breast bright red. Seeing this, Mary declared that the red breast was a sign of the bird’s kind heart, which would pass on to its descendants to wear proudly forevermore. Scottish Wildlife Trust

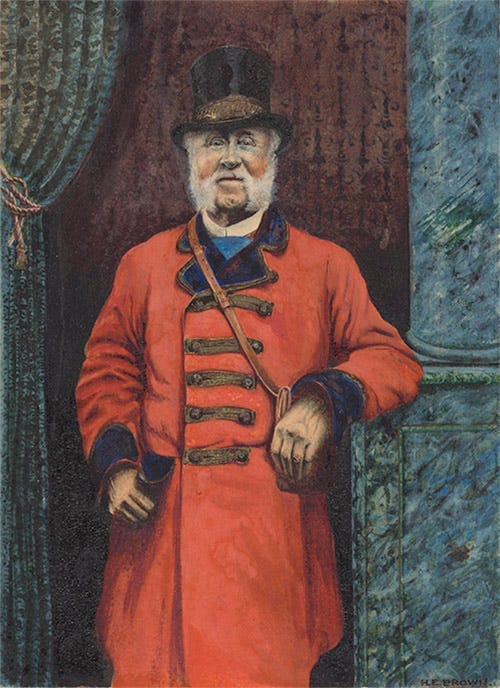

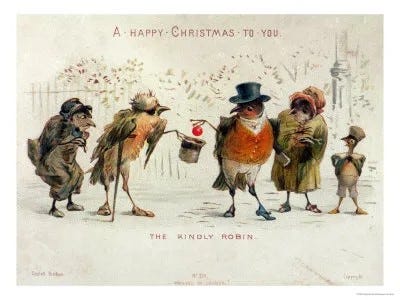

It wasn’t until the Victorian era in England that the robin became associated with the arrival of Christmas, thanks to the British Royal Mail Service. The first uniform issued by the Royal Mail was for the Mail Coach Guards in 1784. It consisted of scarlet coat-tails with gold braids, blue lapels and a black beaver hat with a gold band. The mailmen were nicknamed ‘robins’ or ‘redbreasts’ on account of their scarlet coats and, as the tradition of sending Christmas cards grew in popularity, the image of the robin delivering Christmas mail also became popular.

Although many traditions on the British Isles attribute robins with good luck, it was considered very unlucky to harm a robin or steal its eggs:

“The blood on the breast of a robin that’s caught, brings death to the snarer by whom it is caught”

English folk rhyme.

In some parts of England it was believed that if you killed a robin, the hand that did the deed would shake forever more, develop ugly red weals or boils (Ireland), or even drop off (Shropshire)! In other places in England, it was believed that however you slay the robin, so you too shall be slayed.

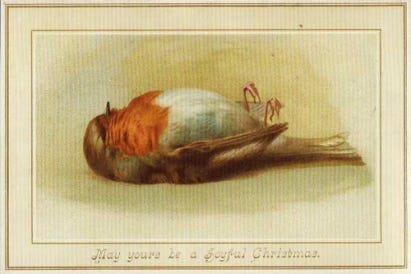

Robins were also at times considered unlucky omens, so if one flew into your house or tapped at the window, it was believed to portend a funeral in the near future. In Devon, it was thought that if a robin landed on the roof and “utters its plaintive sweet,” any baby inside that house would die. The robin was also connected to death through the popular English nursery rhyme, Who Killed Cock Robin.

Who killed Cock Robin? “I,” said the Sparrow,

“With my bow and arrow, I killed Cock Robin.”

Who saw him die? “I,” said the Fly,

“With my little teeny eye, I saw him die.”

Who caught his blood? “I,” said the Fish,

“With my little dish. I caught his blood.”

Who’ll make the shroud? “I,” said the Beetle,

“With my thread and needle, I’ll make the shroud.”

Who’ll dig his grave? “I,” said the Owl,

“With my pick and trowel, I’ll dig his grave.

Who’ll be the parson? “I,” said the Rook,

“With my little book, I’ll be the parson.”

Who’ll be the clerk? “I,” said the Lark,

“If it’s not in the dark, I’ll be the clerk.”

Who’ll carry the link? “I,” said the Linnet,

“I’ll fetch it in a minute, I’ll carry the link.”

Who’ll be chief mourner? “I,” said the Dove,

“I mourn for my love, I’ll be chief mourner.

Who’ll carry the coffin? “I,” said the Kite,

“If it’s not through the night, I’ll carry the coffin.”

Who’ll bear the pall? “We,” said the Wren, both the cock and the hen,

“We’ll bear the pall.”

Who’ll sing a psalm? “I,” said the Thrush, as she sat on a bush,

“I’ll sing a psalm.”

Who’ll toll the bell? “I,” said the Bull,

“Because I can pull, I’ll toll the bell.”

All the birds of the air fell a-sighing and a-sobbing,

When they heard the bell toll for poor Cock Robin.

Sometimes, robins have a more positive association with death as they were believed to be messengers between this world and the afterlife, reflected in the phrase, ‘When robins appear, loved ones are near.’

Robins were also frequently connected with inclement weather. In some parts of Ireland, folklore has it that if a robin entered your house it meant the start of snowy or frosty weather, while in British folklore, hearing a robin nearby meant that storms were on their way. In Nordic countries, the robin was considered a storm-cloud bird, sacred to Thor, the Norse god of thunder, and was said to offer protection from storms and lightning.

The north wind doth blow,

And we shall have snow,

And what will poor robin do then,

Poor thing?

He’ll sit in a barn,

And keep himself warm,

And hide his head under his wing,

Poor thing!

First verse of The North Wind by an anonymous poet (1805)

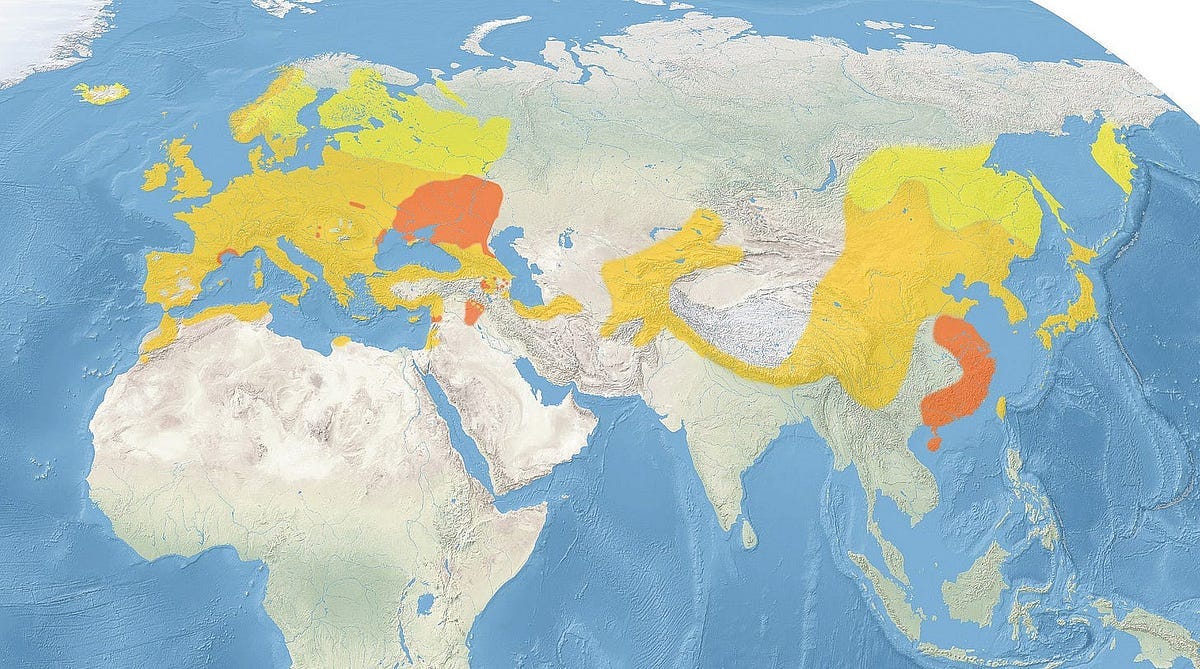

In Eastern Europe, the robin is considered a harbinger of spring rather than Christmas. Robins in these regions migrated south and west to escape the cold, harsh winters. Its return to Eastern Europe in early spring is seen as a sign that the harsh winter is coming to an end, and the earth is beginning to awaken from its slumber.

Interestingly, the European and North American robins actually have orange breasts as there was no word for the colour orange in Europe before the 15th century. The orange colour was simply called ‘red’ or ‘yellow-red’ until oranges (the fruit) began to be imported into Europe in the 15th century and the word orange quickly evolved to mean the colour orange.

Australian Robins

Australia has 49 species of robins, although they are from the family of Petroica, and are not related to the European Erithacus. Many have spectacularly colourful breasts ranging from black and white, to bright pink, rose and yellow. Three of Australia’s robin species have a red breast:

The scarlet robin is most commonly seen in Australia’s Capital region where I live. They are relatively tolerant of suburban environments and are more commonly found in winter as they migrate to cooler climates in summer. They are a lovely symbol for winter and the Yule season in Australia.

The Wren

The wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) is a tiny brown, insectivorous bird, that roosts and hunts in thick hedges and in caves, thus accounting for its Latin name meaning ‘cave hunter’. It has a fine bill, delicate and long legs and toes, a short neck, a round body with small wings and a short, narrow and jaunty tail that is often cocked up vertically. Although small, it has a loud, clear and complex singing voice, ten times louder for its weight than a rooster, and is commonly heard singing its melodious songs throughout Europe. During winter, particularly during prolonged or severe cold, wren numbers and vocalisations decline.

In the UK and most of the European continent, wrens are resident breeders, meaning that they stay in one place and do not migrate, while those from northern and eastern Europe migrate south in the winter, returning to their northerly lands to breed in the spring.

The wren features in folklore across Europe where it is known as the king of the birds, attributed to one of Aesop’s fables, The Wren and the Eagle.

One day, long ago all the birds held a competition to see who among them could fly the highest and thus be crowned king. The small birds soon tired, then the ducks, crows, magpies and all the others except for the eagle, who was certain he would easily win. Just as the eagle began to tire and could ascend no more, the wren, who had hidden in the eagle’s feathers, launched himself off the eagle and flew even higher. Thus the clever little wren won the competition and proclaimed himself king.

A traditional folktale from the British Isles expands this story:

Although the smaller birds were happy with the outcome, the larger birds complained that the wren had won through trickery and cunning. “Why is winning by strength and brawn better than winning by cunning?” responded the wren. “If you are doubtful of my victory, then name another challenge”. The bigger birds discussed this amongst themselves and decided on another competition, the bird that could swoop the lowest would be crowned king. The large birds dived down and glided just above the ground, with the eagle diving the lowest until the wren’s turn when he climbed into a small mouse hole and exclaimed he was the lowest and the king. The large birds of prey were furious and to this day they hunt the king of the birds so he stays hidden in hedges, bushes and caves, while all the other birds visit the clever and cunning wren king for advice.

The wren’s cunning and position as king of the birds also features in a fairytale collected by the Brothers Grimm, The Willow-Wren and the Bear. The wren was called basileus (king) and basiliskos (little king) by famous ancient Greek philosophers, Aristotle, Pliny and Plutarch.

Celtic Druids also called the wren the king of all birds and considered it to be sacred, associated with Taranis, the Celtic god of thunder, which protected the wren from and associated it with lightning. According to an old Celtic superstition, those who take a wren’s egg or nestling will have their house struck by lightning, as would anyone who interfered with a Druid or Druid’s business. The Druids used the wren’s musical songs in divination and a wren’s feather was believed to be a charm against disaster or drowning.

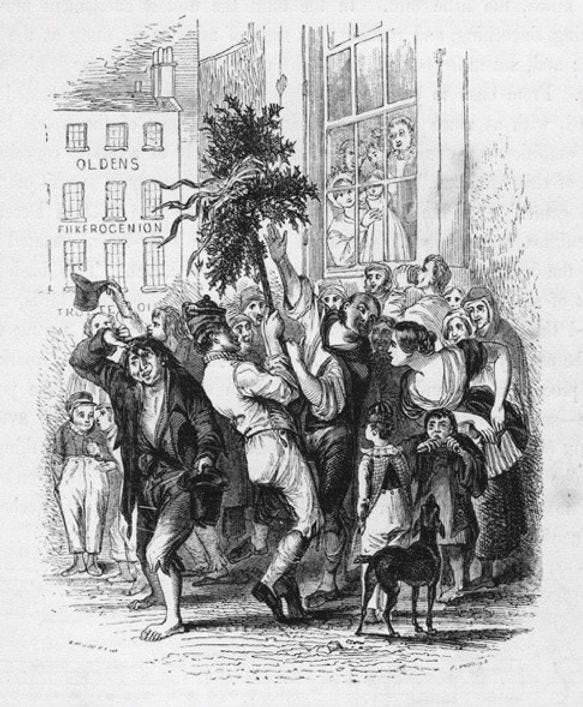

The Wrenboys

An ancient tradition, once widespread across the British Isles, features a special day dedicated to the wren, called Wren’s Day. In Ireland and England Wren’s Day falls on December 26, also known as Boxing Day, or St. Stephen’s Day. In Wales, the day is called, ‘The Hunting of the Wren’ and occurs on January 6. Killing or harming a wren was believed to bring bad luck, except on Wren’s Day. Groups of boys and unmarried young men called the Wrenboys, would hunt and kill wrens, usually by stoning, then tie the wrens to a holly or some other evergreen bush. The Wrenboys would then parade these bushes or poles decked with dead wrens around the town, knocking on people’s doors and asking the householders to pay for the wren’s funeral. Those who refused would have a bird buried outside their house, bringing bad fortune in the year ahead. Those who gifted money were rewarded with a wren’s feather and good luck.

There are many versions of the Wren Song that were and still are sung at the door of people’s houses:

Version 1

The Wren, the Wren, the king of all birds,

St. Stephen’s day was caught in the furze.

Although he is little, his family is great,

I pray you, good landlady, give us a treat.Version 2

The wran, the wran, the king of all birds,

St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze.

Up with the kettle and down with the pan,

Give us a penny to bury the wran.Version 3

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds,

St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze

Her clothes were all torn — her shoes were all worn.

Up with the kettle and down with the pan,

Give us a penny to bury the wran.

If you haven’t a penny, a halfpenny will do

If you haven’t a halfpenny, God bless you!

Once the Wrenboys collected enough money, they would head to the local pub to drink, sing and dance, with the decorated pole or bush in pride of place. These days, no birds are killed but rather a stuffed or artificial wren is tied to the holly pole or bush, or carried around in a cage decorated with ribbons.

There are several theories about the origins of the wren celebration. It’s likely that the traditions of Wren Day pre-date Christianity, which means that the hunting and killing of the wren is likely connected to an ancient sacrificial ritual to bring in the new year.

On the Isle of Man, the hunting of the wren, called shelg yn drean, was associated with the Queen of the Faeries, who was called Tehi Tegi. Tehi Tegi was so beautiful that all the men of the island neglected their homes and fields to court her. She soon grew tired of their incessant and relentless pursuit of her and like a pied piper for enamoured men, she led them to a river or the sea and drowned them all. When she was confronted by the remaining islanders she turned into a wren and escaped. As punishment, she was made to remain in the form of the wren to be hunted and killed every year on December 26.

The video (4:26 mins) below shows the traditional Manx song Hunt the Wren sung in full at the Tynwald Inn in 2018:

The video (5:17 mins) below is a medley of Celtic tunes related to the hunting of the wren, played on various instruments, including:

Hunting the Wren from Wales

We’ll Hunt the Wren from Ireland

Wren An Dro from Brittany

Hunt the Wren from the Isle of Man

Death of the Wren from Scotland

The Wren’s Nest from Ireland

You can watch traditional Wrenboy celebrations from the 1960s and 70s in this video (8:16 mins) from Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTE):

The video below is a lovely documentary (15:02 mins) from Leitrim in Ireland about the mumming, straw boys and wren boys traditions.

It is also possible that Christians, understanding the importance of the wren to the Druidic Celts, used the killing of the wren as a symbolic murder of the reviled pagans and their beliefs. The wren’s connection to St. Stephen springs from a Christian legend of St. Stephen hiding from the Jews, when the wren alerted them to his whereabouts, leading to his capture and death by stoning. The wren is also connected to treachery and betrayal in Irish and British folklore. Wrens were infamous for alerting and waking sleeping armies, be they Vikings or later Cromwell’s soldiers, as local forces were about to spring their ambush.

Although the wren is a small and plain-looking bird, its humble appearance belies its power, cunning and influence. It is truly the king of the birds and a potent symbol of the winter season.

Australian Wrens

Though not related to the European wren, Australia has its own species of beautifully coloured wrens, called fairy-wrens. The Superb fairy-wren, with its shimmering blue and black mask and jaunty tail, is a common visitor in my garden. The flashy male and his dowdy but cheerful harem never fail to make me smile whenever they visit, always singing happily.

For such little birds, the robin and the wren have big stories.

If you are living in the southern regions of Australia, you will probably notice signs that the season has started to turn, Yule has ended and spring is stirring. Snowdrops are blossoming, daffodils, jonquils and tulips are emerging from their slumber. Next week we celebrate Imbolc, the quickening and the first stirrings of spring. Stay tuned for next week’s article as we delve into the traditions of Imbolc, and the history of Brigid’s Day. We’ll also explore the local Ngunnawal season of Djambari and what seasonal changes can be observed in this part of the world.

Share this post