Dear Readers,

It’s wonderful to be back after a month-long break, especially with Christmas on the horizon. We will be exploring Christmas-themed episodes every Thursday of this month including:

Episode 25 (Dec 5) - A Very Aussie Christmas (this episode)

Episode 26 (Dec 12) - The History of Santa’s Elves: The nice and the not so nice

Episode 27 (Dec 19) - The Origins of Santa and His Reindeer

There are also supplemental editions scheduled every Monday until Christmas that will contain links and descriptions to two or three previous episodes about winter, Christmas and Yule:

2 December - Winter Icons, Winter Solstice and Mother’s Night

9 December - Deck the Halls, Strike the Chorus and Join the Feast

16 December - Scandinavian Yule Celebrations and the Origins of the Yule (Christmas) Tree and Log

23 December - Scandinavian Yule Creatures and Two Small but Mighty Birds

Now, let’s get on with the main show for today, exploring a very Aussie Christmas. Here in Australia, we celebrated the onset of summer on December 1st. Many people start decorating for Christmas on this day and I was excited (probably even more than my children) to deck the halls with Aussie Christmas music blaring, gorging on cherries and macadamia nuts. Last year I posted an article about my Aussie Christmas Carols playlist and one about my Aussie-themed Christmas decorations with plenty of pics if you’re interested.

In this article, we’ll explore:

Aussie summer Christmas traditions (Santa on a firetruck, native Christmas trees, hay bales and farm gates, beach Christmas and Aussie Christmas food)

Awkward colonial Christmas celebrations

Summer celebrations of our First Peoples

Aussie Christmas Traditions

Santa on a Fire Truck

In country towns all across Australia, Santa arriving at community Christmas events and parades on a fire truck has become a joyful tradition. It makes sense from an aesthetic point of view as our fire trucks are bright red, they’re loud and the flashing lights add to the excitement but there’s also a deeper, more meaningful connection. December in Australia is typically hot and dry, with the threat of bushfires an ever-present spectre at this time of year. Many towns and cities have felt the devasting effects of bushfires and the state-based volunteer fire services are vital to many communities.

In my state of New South Wales, they’re called the Rural Fire Service (RFS) and in my town, they don’t just fight bushfires, they also fight structure fires, car fires, attend motor vehicle accidents, assist the SES during flood events, assist local police and ambulance and are deeply plugged into our community. They are heroes, every day of the year, especially during the Christmas season.

Last year our local RFS not only brought Santa to the community Christmas event in a firetruck, but they took Santa on a ride around our town, mapped out and shared the routes and times, used an app so the community could monitor their progress live, and delivered little bags of lollies and Christmas wishes to the children in our community. They’re doing the same again this year. What a magical gift for everyone in the town, thank you Bungendore RFS!

For communities that are too remote or small to have their own RFS or for those living on the big stations (huge farming properties in the outback), Santa often comes to the local pub, community hall or camp draft arena, in the back of a ‘ute,’ truck, tractor or even on horseback. The state police services have also been known to chauffeur Santa around.

I don’t like to share ads, especially not for large corporations but this brilliant ad (1:30 mins) shows what might happen if Santa were to crash on an outback station, to give some Christmas-inspired context to life on some of the remote, outback properties.

Native Christmas Trees

Before conifers from the northern hemisphere were imported into Australia, it was common to decorate native trees and use Australian native flowers and boughs to ‘deck the halls’. This celebration of Australian native flora is becoming more popular once again.

These days there are a lot of choices for Christmas trees. Christmas tree farms have popped up around Australia, producing traditional conifer trees for the live-cut Christmas tree market. The Albany Wooly Bush Adenanthos sericeus, is becoming a popular live native Christmas tree species and branches of Eucalyptus and wattle are used to create trees and wreaths. Our household decorates a plastic fir tree with Aussie and summer-themed ornaments for Christmas with colours of aquamarine, gold, red and pink, candy canes, Australian native flora and fauna, and treasured decorations made by our children.

Some Australian native flora and fauna have been crowned with the ‘Christmas’ moniker. The New South Wales Christmas Bush, Ceratopetalum gummiferum, is an iconic native Australian bush that heralds the festive season with showy, sepals that turn scarlet after blooming with small white flowers in spring. In Western Australia, the hemiparasitic tree, Nuytsia floribunda, has been nicknamed the WA Christmas Tree for its fiery show of flowers in December. The Victorian Christmas Bush, Nuytsia tasmania, can be found in coastal and sub-alpine areas, from southern Queensland to Tasmania and flowers profusely through the Christmas season.

Christmas Beetles, Anoplognathus spp., were once a ubiquitous sight across Australia during the Christmas season. These beautifully iridescent beetles, ranging from brown to bright jewel-like greens, have become increasingly hard to find, disappearing completely from some regions. The University of Sydney is asking the general public to take pictures of Christmas beetles and upload them to an app called iNaturalist. I use this app frequently to identify plants and it’s good to see how the general public can help scientists and conservationists figure out what is happening with our Christmas beetle population. The video (4:07 mins) explains the Christmas Beetle Project.

Hay Bales and Farm Gates

Across Australia’s rural landscape, a new tradition has been quietly growing for the last 20 years; farmers sharing the Christmas spirit by creating huge hay bale Christmas displays in their paddocks or decorating their farm gates.

The origins of this tradition aren’t known but rural communities and homesteads in Australia can be extremely isolated due to the vast distances between properties and townships. This is one way that people connect and share Christmas joy with passersby.

Ayla’s Christmas Wish, written by Pamela Jones and illustrated by Lucia Masciullo is a lovely children’s Christmas book we’ve added to our collection that explores the magic of hay bale Christmas decorating.

Christmas is coming and Ayla wants a snowman just like in her book, but there is no snow to be found in her drought-stricken town, not even a drop of rain. Only bales of hay.

Ayla's Christmas Wish is inspired by the small, south-west Victorian town of Tarrington, which runs a hay bale design competition each year. This book compares European Christmas traditions with the reality of a hot, dry Australian summer. Behind the story of Ayla wishing for a snowman, there is a town wishing for rain.

This story celebrates a community at Christmas-time, and highlights the importance and beauty of small-town resilience.

Beach Christmas

Australia is an island continent with vast stretches of coastline and the majority of our population lives along much of these coastal regions. Christmas at the beach is a tradition for many families, whether they live nearby or travel hours to their regular holiday homes or caravan parks. It is a joyful tradition for caravan parks packed with holiday homes, caravans, and tents all sparkling with Christmas decorations. Surfboards, fishing reels, jet skis and other fun water ‘toys’ are scattered everywhere with excited children playing and parents/grandparents watching contentedly. Many of the popular caravan parks organise fun Christmas activities, movies and visits from Santa.

Photos below from KidSpot.com.au

Christmas at the beach is also a fun experience for backpackers and international visitors, especially the famous Bondi Beach in Sydney.

Australian Christmas Food

Australia is a multicultural country and there are many ways we like to celebrate, especially when it comes to food. Families with immigrant backgrounds often prepare their favourite festive foods. However, due to the typically hot weather, the traditionally northern hemisphere hot Christmas meal frequently gives way to cooler options that require less preparation.

Many Australians celebrate their main Christmas meal at Christmas Day lunch. The festive toast is made, just a ‘cheers and Merry Christmas’ in my household. Crackers are popped, paper hats worn and silly jokes are read out while prawns, ham, seafood, and charcuterie plates are served and eaten. This is accompanied by sides of cold salads that often include coleslaw, potato salad and other summer vegetable concoctions.

Grazing platters of cheese, vegetables, nuts, dips and crackers often feature as entrees while seasonal fruit such as stone fruit (cherries, apricots, plums, peaches, and nectarines), berries and tropical fruit (mangoes, lychees, pineapples etc) are presented after the main meal alongside dessert. Christmas pudding is still a popular option but you can’t go wrong with a pavlova covered in whipped cream and fresh fruit or a decadent Christmas trifle.

I like to bake a Ginger Cake for Christmas Eve dessert, from an eggless ration recipe passed down from my Grandma Doris, an Australian Army cook during WWII. It is a lovely, moist and delicious-smelling cake that I also use for my Yule log cake at Yuletide and for my children’s Kagemand (‘Cake Man’) birthday cakes. I jazz up the recipe for the Aussie Christmas cake with an Australian bush spice mix called Oz el hanout from a local producer, Bent Shed Produce, which contains pepperberry, lemon myrtle, wattleseed, aniseed myrtle, forestberry herb, dried finger lime, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, nutmeg, coriander, and cumin. Baked in a bundt pan, drizzled with white lemon icing and decorated with Australian native flowers, it’s a lovely homage to my beautiful country and the hot season. Leftover cake is used in the Christmas lunch trifle.

Bluey

There’s no other show on the planet that reflects our Aussie way of life better than the gorgeous kids’ show Bluey. Two wonderful episodes were created that describe the traditions and spirit of an Aussie Christmas. Do yourselves a favour and watch them on your relevant regional streaming service.

This wonderful piece by Robert Skinner in The Monthly, A Beautiful Mess: When European Christmas meets Australian Suburbia is a rollicking good piece of writing that captures the incongruities, the joys and the essence of our Australian Christmases.

An Awkward Colonial Christmas

Most Australians will know that Australia is home to some of the oldest surviving, continuous cultures in the world with our First Peoples living and thriving on this continent for some 60,000 years. The next section explores First Peoples’ cultures and seasonal practices. This knowledge and seasonal cultural practices were disrupted and often permanently eradicated by British colonists, who imposed their own beliefs, cultures, traditions and practices on the country that was to become Australia.

British traditions and practices often sat awkwardly against Australia’s seasons and environment, none more obvious as Christmas, which falls in the middle of our very hot summers. Even now, there is still a struggle between imported Christmas traditions from the northern hemisphere, clashing with summer in the southern hemisphere. It is rather odd to be singing about and decorating with themes of winter, snow, cold, warm food and drinks, while we are sweltering under the hot summer sun. It would have been quite a big culture shock for the British, especially those early colonists. Before exploring how the Australian colonists celebrated this time of year, I would like to state that:

This entire publication is dedicated to reviving as many seasonal practices from my own Western and Northern European background within the appropriate seasonal cycle here in Australia. I do this to try and reconnect with and understand my ancestral heritage, and the deep history of my people. This also includes telling the truth and not shying away from the ugly and difficult aspects of my connection to the place and Country I call home, through the brutality of colonisation. I will explore these difficult truths in January. For now, I want to acknowledge that talking about colonisation may hurt some readers and I acknowledge the validity of those hurts. I am deeply and forever will remain sorry for what has and is happening to this beautiful Country and its precious First Peoples. May you always be given the dignity, respect and honour you deserve, and may you, your cultures, and your connection to Country thrive so that we all may thrive together.

Colonial Christmas

The Daily Telegraph gives a good account of the first colonial Christmas in Botany Bay and by all accounts, it was pretty grim. Early colonists were entirely reliant on Britain for food supplies as they were unfamiliar with and unable to see the abundance of food in their new environment. Their seed crops were destroyed by weevils, and what little was grown, failed in the harsh environment. The entire colony was on strict rations, with hardly an exception for Christmas, unless you were a guest of Governor Phillip of course. Although even then, “Concerning that dinner, the least said the more generosity” reported Judge Advocate Capt David Collins about Christmas lunch in Sydney Cove in 1788.

During the early stages of colonisation, religious celebrations were not popularly observed by the majority of colonists, other than for marriages or baptisms. Convicts generally came from the poorer classes who, even before being shipped to Australia, did not have time nor inclination to attend religious services. Many had to work on Christmas Day for the wealthier classes. Pastor Richard Johnson complained in a letter to a friend in England that “inhabitants of Sydney Cove would prefer the erection of a tavern or a brothel than a church”.

Convict rations were abysmal with no dispensation for Christmas, they were provided with bread, salted beef or pork, perhaps fish, and yellow peas (pease). The next year in 1789, while the Governor and his guests dined on turtles and vegetables, the convicts were on reduced rations of salt pork, flour and pease.

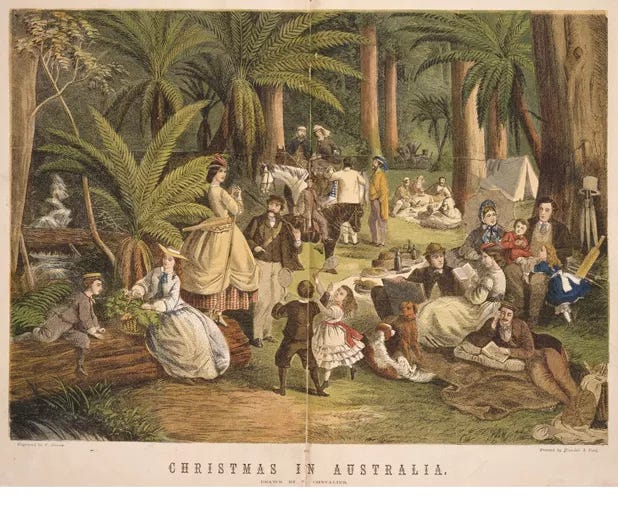

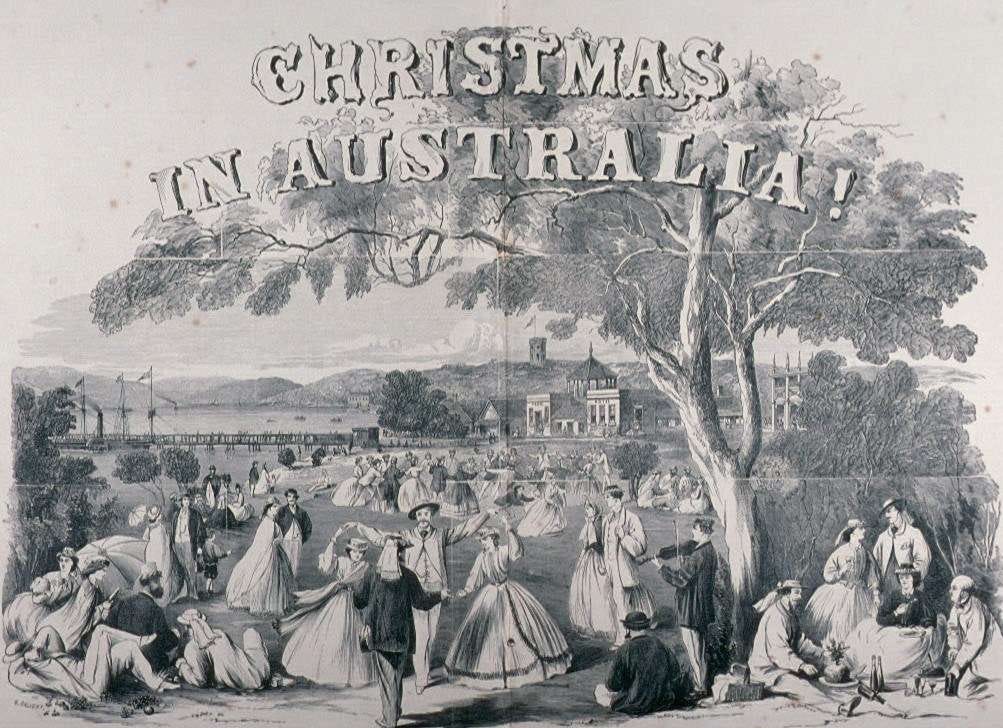

Over the next hundred years, conditions got better for the colonists as they started farming and taking more land. Attempts were made to celebrate the positive aspects of Christmas in Summer.

The 1885 Sydney Mail described a Christmas scene in the colony:

… there is an air of Australian summer… no sense of snow or ice whatever… Fern fronds [and greenery] seem still to hold the sunshine and… the full glow of the morning and the full flood of light… streaming through the window and giving a full illumination to the room. Many thousand such Christmas scenes as this will NSW see this week, and many mothers and children will experience pleasure in finding their familiar Christmas preparations [shared throughout the colony]. From Sydney Living Museums Blog.

This newspaper article from Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers describes a typical Australian Christmas in 1872:

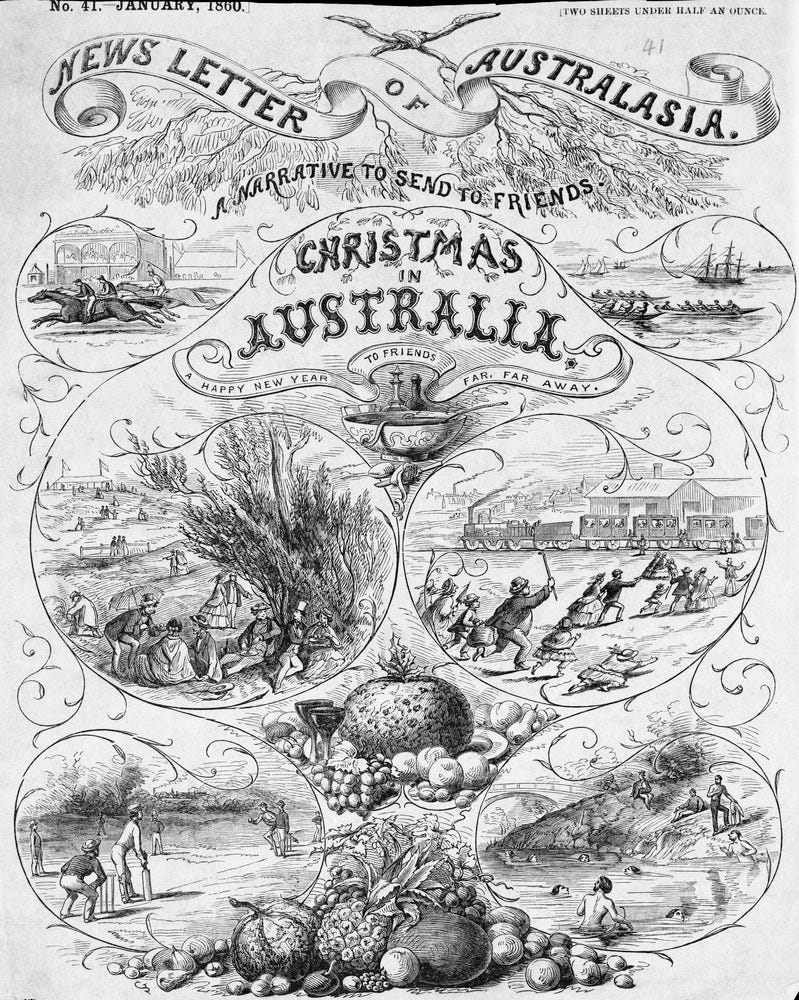

Adventide, despite the absence of the old world associations in the shape of carols, waits, snow, and frost, with the yule log, the mistletoe, the holly with its scarlet berries and the family gatherings, still continues a time of deep rejoicing in this sunny southern land. In the far bush and on the busy gold-fields, in the crowded city and the quiet hamlet, Christmas brings with it associations far different to its surroundings in the old world. They are characteristic of the new country, yet they lose nothing of their intensity in the change of locality and climate. Here the glad celebration of the season takes place, for the most part, under the broad canopy of Heaven; and picnics, athletic sports, and trips over the briny waves suffice as outlets to the feelings. In the wild bush, round the night fire, yarns are spun by the travelling stockmen ; and men live over again the scenes of their youth. Source: The Golden Christmas Cake in Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 1872

Here’s another article comparing the difference between the northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere Christmas, this time from the Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 1852.

As if to vindicate the climate of the sunny South, the cool breezes which ushered in Christmas have given place to a sirocco from Sturt's Desert. What a vast stretch of the imagination is required to realize to the mind's eye an English Christmas, during a hot wind; or being subjected to a scorching summer heat to ruminate on snow balls, skates, chilblains, red noses, muffs, great coats, and comforters, and fancy one's self one of a dozen keeping the pot a'boiling down a long slide with the thermometer at 120. You can't do it, it's no use. What are prize oxen, prize sheep, prize pigs, rabbits, and poultry, misseltoe and holly, plum pudding, and snap dragon, speculation, and blindman's buff? they are only an indistinct dream, the memory of something disconnected with the present. In the north, all is top coat, and comforter, muff, tippet, and boa, piercing winds, and drifting snow, whilst here, if we become aboriginal in our habits, coolness would not follow. Our Christmas requires refrigerating to become enjoyable, instead of coughs, and pulmonary attacks, closed doors, stuffed key holes, and listed windows, we have langour, furious blasts, whirl winds, and doors wide open, courting every current, and in full length recumbency, open mouthed, we wait for a zephyr. Had we power, we would move that Christmas be postponed till this day six months, and that we do now proceed to consider these the Midsummer Holidays. Source: Christmas Times in the Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 1852

Bush Christmas

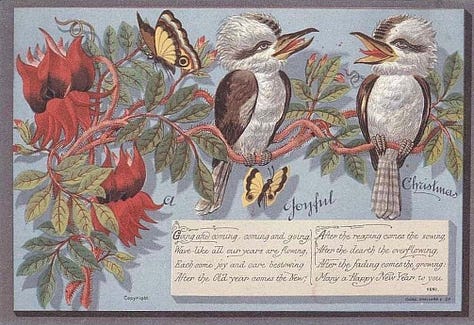

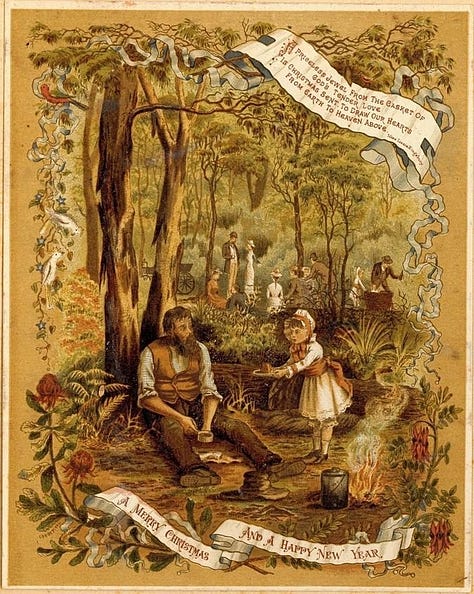

By the middle of the 1800s, British Australia was beginning to develop its sense of identity separate from Britain. The Bush Christmas became an icon around which the first Australian fables were built. Famous Australian poet and balladeer, Banjo Patterson, wrote his popular poem Santa Claus in the Bush, and Australian Christmas cards began to celebrate the uniquely Australian flora, fauna and Christmas weather.

Christmas Pudding

Although British Australians began adapting many of their old Christmas traditions to their new country, one particular tradition has been stubbornly (and joyfully) maintained. I have written about Christmas Pudding in a previous article on traditional Christmas desserts, from the season of Yule in June/July, Australia’s winter. Christmas pudding, as well as Christmas cake and mince pies, have retained their prominence in Australia and are still popularly baked or bought at this time of year.

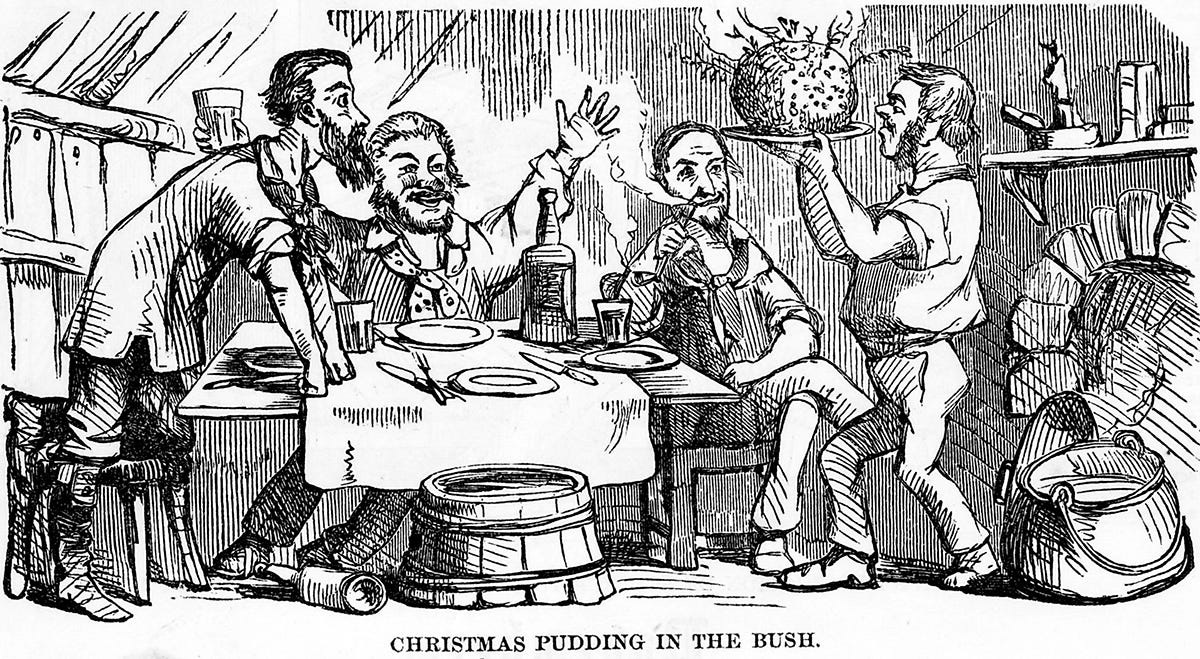

In the early stages of colonisation, rations for military and civilians included flour, sugar and rum, with the addition of beef suet and raisins at Christmas to allow each household the ingredients for their Christmas puddings. As Australia’s free society became established, colonial merchants began importing and selling the ingredients needed for a ‘proper’ Christmas pudding, including brandy or rum, raisins, currants, figs, and almonds as well as spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon and allspice. Even miners on the goldfields in the 1850s, living in very basic conditions, worked to buy and prepare their precious Christmas ‘pud.

Eventually, Australia was able to produce the fruit, alcohol and nuts needed for Christmas pudding and imports of these ingredients from Britain disappeared, although spices from the East Indies still needed to be shipped in. An article in The Conversation describes How the Christmas Pudding Evolved with Australia.

The importance of Christmas pudding for Australian Christmas traditions becomes very obvious if you search for ‘Christmas Pudding’ in the National Library of Australia’s Trove archives. Hundreds of thousands of newspaper and magazine articles giving recipes and favourite tips for Christmas pudding can be found spanning across all regions of Australia from the very earliest prints until now.

Tea and Sugar Train

While British Christmas traditions were being adapted to the Australian environment in the developing cities and towns across Australia, a train service began to spread unique Christmas traditions deep into rural and remote Australia.

The video (7:51mins) below about the Tea and Sugar Train was filmed in 1954 by the Commonwealth Film Unit and provided by the National Film and Sound Archive.

From Australian Trains

Perhaps one of Australia’s most loved trains, the ‘Tea and Sugar’ service commenced in 1915 to service some of the more remote places along the Trans-Australian route. Although it started by simply providing goods and services to workers in these remote locations, the service increased over time, providing more to a number of the isolated communities along the railway line between Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie.

For many who lived and worked in these remote communities, the train changed their lives. The ‘Tea and Sugar’ carried more than just that. The train also carried fresh meat in a butchers van as well as a variety of groceries and even provided pay and banking facilities. Best of all, the prices of goods on the service was comparable to the major towns and cities.

Firmly placing the service in the hearts of Australians, in the early 1950s the train even carried Santa Claus at Christmas time, distributing presents to children all along the railway route. The ‘Tea and Sugar’ was also used by the GPO for its mail run to these remote locations, with mail delivered to the station master where it could be collected by employees and families. The service soon expanded to include welfare services such as medical service, a children’s toy library and even a separate car housing a theatrette.

The arrival of the train was a cause for great excitement, breaking the monotony of day to day life in these isolated locations. The people in the towns often referred to the train’s arrival as ‘Tea and Sugar Day’ and many of the women celebrated the occasion by getting dressed up to meet the train at its siding in style.

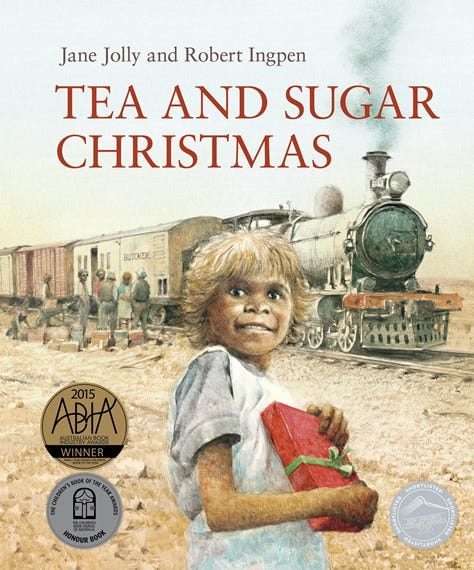

Children’s book author Jane Jolly wrote a book about the joy of the Tea and Sugar train at Christmas.

From Tea and Sugar Christmas:

For 81 years, from 1915 to 1996, the Tea and Sugar Train travelled from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie once a week. It serviced the settlements along the Nullarbor Plain, a 1050-long rail link. It was a lifeline. There were no shops or services in these settlements. The train carried everything they needed—household goods, groceries, fruit and vegetables, a butcher’s van, banking facilities and at one time even a theatrette car for showing films. The biggest excitement for the children was the first Thursday of December every year, when Father Christmas travelled the line. He distributed gifts to all the children on the way, including those of railway workers, those in isolated communities, and station kids.

First Peoples’ Summer Celebrations

Before English colonists ever stepped foot on this land, summer was an important time for our First Nations, although it was called different names, started and finished at different times and had different characteristics depending on the region and culture of its First People. The swing of the seasons was not marked by dates on a calendar but rather by the weather, the landscape and the behaviour of Australia’s native flora and fauna. These events on Earth were mapped to the movement of stars and constellations in the night sky by our First People, who developed advanced astrological and environmental knowledge. We’ll take a closer look at this advanced knowledge in a future article but in this article, let’s explore this time of the year through the eyes of some of our First People.

Ngunnawal - Australian Capital Region

The Ngunnawal, the traditional custodians of my region, have six seasons and the start of December marks the middle of ‘true summer,’ Winyuwangga. The weather is usually hot and dry, with a high risk of bush and grass fires (although this year in my region we have suddenly been inundated with rain, storms and cooler temperatures). Seeds from grasses, wattle and lomandra are harvested and stored or ground into flour for damper (unleavened bread cooked on fire coals).

Native grasses are perennial and have adapted to Australia’s harsh and variable climates and low-fertile soils. Research is being conducted on ‘Kangaroo Grass’ (Themeda triandra) in particular, as a perennial crop that can be used for flour in the same way as wheat as it thrives in the harsh Australian environment. It has 40 per cent more protein than wheat and is apparently quite tasty. It also stores more moisture than European crops and creates its own micro-climate in which native insects thrive (read this article from ABC News - Could native crop, kangaroo grass, become a regular ingredient in bread and help farmers regenerate land? for more information).

Berries from the Dianella (Blue-Flax Lilies) are also gathered and eaten fresh or dried and stored.

By December, the culturally significant Bogong moths have mostly migrated south from their winter homes in the northern parts of New South Wales and south east Queensland to their cool summer sanctuary in Australia’s Alps, the Snowy Mountains. First Nations mobs from across the region also traditionally travelled along their song lines to gather together in the Victorian Alps for feasting on the protein-rich Bogong moth, participating in ceremonies, trading and negotiating.

These ancient traditions have almost been lost as a consequence of colonisation and even the survival of bogong moths is now threatened by light pollution, pesticides and urban development.

Bardi - The Kimberley Region in Western Australia

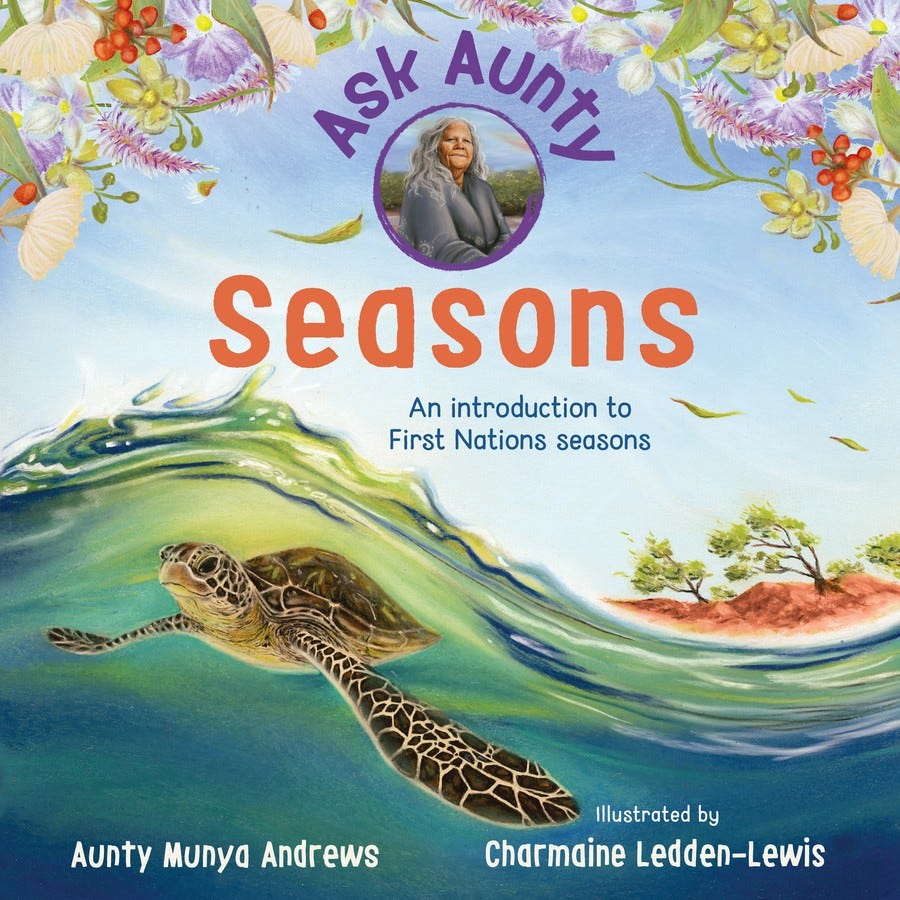

Aunty Munya Andrews, an Aboriginal Elder from Bardi Country in the Kimberly in Western Australia, has written a wonderful children’s book that introduces the seasons of the Bardi people.

The Bardi are Saltwater People, meaning that their Country and culture are connected to the sea. They also have six seasons reflecting the wet and dry seasons of Northern Australia. November to January is considered Lalin or ‘married turtle season’. During this time, sea turtles lay their eggs. It is the start of turtle hunting season and the Bardi also collect turtle eggs. The bush banana (Leichhardtia australis) fruits are harvested and eaten, and fish are fat and plentiful, especially the prized bluebone or blue tuskfish, Choerodon cyanodus, which has blue teeth and skeleton. The end of Lalin is marked by tropical storms that build in intensity until the season transitions into the wet season, Mankal.

Resources

Colonised countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and America, were populated by First Peoples who knew their land and its seasons much more intricately than we do now. This knowledge is still there if you care to look. In Australia, the Bureau of Meteorology has a map that details Indigenous Weather Knowledge and the CSIRO has a similar Indigenous Seasonal Calendars page. You could also try contacting your local Aboriginal Land Council, or Aboriginal Culture group or even better, book a cultural tour and ask your tour guide in person.

I hope you enjoyed this rather long article about Aussie Christmas. I’d love to hear your stories and memories about your Christmas celebrations in the Comments section. Stay tuned next week for a fun exploration of Santa’s elves: the nice and the not-so-nice (and often downright frightening).

Share this post