Although spring blossomed and emerged in its usual manner, strong winds have thrashed the south of Australia most days this month and made the usually temperate month of September rather unpleasant. The wind and illness didn’t stop me from celebrating Eostre and Spring Equinox on Sunday although things didn’t go according to plan: I didn’t wake up in time to mark dawn, my gluten free Easter Bread was too heavy and my marshmallow didn't set (I couldn't find gelatin at the store so tried substituting it with arrowroot, but had no idea how the make the substitution work).

In saying that, it was still fun to share these small and seasonal family traditions and there's always next year to get the recipes just right (and find an old-fashioned rabbit mould for the marshmallow). Maybe I can even have that Eostre garden party I've been dreaming about. I hope you all had a lovely Spring Equinox (Autumn Equinox for my Northern Hemisphere friends) too!

This week we are still immersed in the spirit of the Spring Equinox, exploring the history, traditions and folklore of Easter eggs, games and foods.

The Origins of the Easter Egg

During Spring, many species of birds begin to lay eggs. Although there is no written record of pre-Christian traditions and beliefs connecting eggs to the celebration of Spring, it is commonly recognised that eggs were a potent symbol of Spring and that Christian traditions and practices involving Easter eggs most likely originated from pagan roots. In these ancient belief systems, eggs were often connected to the creation of the world, or universe. Ancient Egyptians believed the Sun God Ra hatched from a primeval egg.

According to Hindu myths, eggs symbolise the structure of the universe, with the shell representing the heavens, the egg white representing the air, and the yolk representing the earth:

The Sun is Brahma—this is the teaching. A further explanation thereof (is as follows). In the beginning this world was merely non-being. It was existent. It developed. It turned into an egg. It lay for the period of a year. It was split asunder. One of the two egg-shell parts became silver, one gold. That which was of silver is this earth. That which was of gold is the sky … Now what was born therefrom is yonder sun. Source: Chandogya Upanishads in Scientific American

Zoroastrians believe the egg was laid by the force of good, representing the universe and the midway point between good and evil.

Finland also has a creation story involving eggs:

Luonnotar, the Daughter of Nature floats on the waters of the sea, minding her own business when an eagle arrives, builds a nest on her knee, and lays several eggs. After a few days, the eggs begin to burn and Luonnotar jerks her knee away, causing the eggs to fall and break. The pieces form the world as we know it: the upper halves form the skies, the lower the earth, the yolks become the sun, and the whites become the moon. Source: Scientific American

Eggs are particularly important in Slavic mythology. One myth related to the widely worshipped sun god Dazhbog, tells that birds were the chosen creatures of Dazhbog, as they were the only beings that could come near him in the heavens. Their eggs were considered magical objects and the source of life, and they were honoured during Spring festivals.

In China, a Taoist creation myth tells that the universe began as an egg in which a primeval giant named Pangu was born. When he emerged, Pangu broke the egg into two parts, the upper part becoming the sky and the lower part becoming the earth. When Pangu died his body parts became the sun, moon, landscape and living things. The Chinese/Burmese/Thai ethnic group known as the Palaung believed they originated from a Naga (dragon) princess who laid three eggs. The Chin people of Burma/Myanmar/India believed they originated from the egg of a great crow.

In the first century AD, the symbol of the Phoenix was adopted by early Christians to represent the resurrection of their god/prophet Jesus Christ. The Phoenix was a beautiful mythical bird that was said to live for hundreds of years until it died in flames and rose again from its own ashes or in some stories, from the egg it laid before its death.

The depiction of the Phoenix as a symbol of Christ’s resurrection was replaced by the Phoenix’s egg. Many scholars believe that early Christians in the Middle East and Mesopotamian regions borrowed Easter traditions and practices from the Persian (ancient Iranian) celebration of Nowruz (now meaning ‘new’ and ruz meaning ‘day’). Nowruz was the Zoroastrian celebration of the new year at the Spring Equinox, which is still celebrated by Persian (Iranian) communities and diaspora. During Nowruz celebrations, special items were placed on a ceremonial table called the Haft Sin/Seen table (Haft means 7 and Sin/Seen is the Persian word for ‘s’), to attract and represent positive attributes for the new year, including:

Sabzeh (grass or sprouts) symbolising rebirth

Seer (garlic) symbolising health, medicine, and protection against evil

Seeb (apple) symbolising health, family and safety

Serkeh (vinegar) symbolising patience and wisdom - it replaced sharab (wine) which was forbidden under Islamic law after the Islamic conquest of Persia

Senjed (dried oleaster - wild olive) symbolising love and affection

Sumac (the spice) symbolising the sun, sunrise, life and prosperity

Samanoo (boiled, ground wheat berries) symbolising happiness and the sweetness of life

In addition to the seven Sin/Seen items, a mirror, a holy book (either the Islamic Quran, the Christian Bible, Zoroastrian Avesta, or another holy book depending on the family’s religion) and candles were often placed on the table, as well as colourfully dyed and decorated eggs.

Christian Easter Egg Traditions

As already mentioned, early Christians borrowed heavily from Middle Eastern cultural traditions including the egg as a symbol of resurrection. Christians began to dye their eggs red for the Paschal/Easter season to represent the blood of Christ, and this tradition is still practised in the Greek and Eastern Orthodox churches.

During the First Council of Nicea in 325 AD, the practice of long fasting (similar to the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan) was standardised. It began in late winter and lasted 40 days, in order to honour Christ’s fast of 40 days in the wilderness, as recorded in the Christian Gospels. It also served as a physical and spiritual cleansing after the excesses of the Christmas season. This practice was eventually called Lent, from Germanic roots referring to the ‘lengthening’ of days and the coming of Spring. Lent is not a complete fast but commonly involves the exclusion of oil, meat or meat products, dairy and eggs. Eastern churches still maintain strict fasting but many Western churches have relaxed the Lenten restrictions allowing people to choose what foods, or even activities, they wish to restrict during Lent.

Shrove Tuesday, the day before the start of Lent, is known as Pancake Day in English-speaking countries, Mardi Gras (fat Tuesday) in French-speaking countries, and Carnival (English spelling) in Portuguese, Spanish and Italian-speaking countries. It is a time for celebration and for cooking and eating dairy (milk, cheese and butter) and egg-based foods such as pancakes (English), crepes (French) or blini (Eastern European) in order to use up stores in the lead-up to Lent. In England, children commonly went door to door on the Saturday before Lent to beg for eggs as one last treat before the beginning of the fast.

Lent ends on Easter Sunday often with a blessing of the food, particularly eggs, which are eaten first (see the previous episode, Episode 18 - Spring Equinox: Eostre, Easter, Witches and Bunnies to learn about the computation of Easter dates).

Various superstitions have evolved around eggs at Easter time. For example, eggs laid on Good Friday and kept for 100 years were said to turn into diamonds. Some believed that eggs boiled on Good Friday and eaten on Easter Sunday promoted fertility and prevented sudden death. If your Easter egg had two yolks, you would soon be rich. Whoever has an egg that does not shatter when knocked against another’s will have good fortune for the rest of the year.

Eggs, which were still being produced by chickens throughout the Lenten season, were often hard-boiled in order to preserve them through the fast until they could be eaten at Easter. Eggs were also blown (their contents blown out through a small hole) to preserve the shell. Both blown and hard-boiled eggs were frequently decorated as we will explore in the next section below.

Easter Egg Decoration

The decoration of eggs was not necessarily connected to Easter and is thought to have begun as far back as the Middle Stone Age, with designs etched onto the surface of eggshells. Engraved ostrich eggs found in Africa date back 60,000 years. Gold and silver representations of ostrich eggs were commonly found in ancient Sumerian and Egyptian graves and were thought to symbolise nobility and connection to the gods. Intricately carved ostrich eggs were luxury items in the Mesopotamian and Mediterranean regions during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Eggs decorated in connection to Spring celebrations were first documented in descriptions of the very old Egyptian national festival, Sham Ennessim, which marks the beginning of Spring and originated from the ancient Egyptian Shemu festival. The decorating, displaying and eating of eggs also forms part of the ancient Persian and Turkic Spring Equinox celebration of Nowruz, which we discussed in the previous section. Slavic cultures have a very old pre-Christian tradition of decorating eggs during Spring using various techniques such as batik (wax-resist) dyeing, applique, scratch-work, wax encaustic and carving. The most well-known of these Slavic decorated eggs is the Pysanky.

Pysanky

Pysanky and other Slavic styles of decorated eggs were decorated for Spring festival celebrations, called Velkiden, which means ‘Great Day,’ now connected to Christian Easter celebrations. However, these eggs were not originally Christian symbols nor were they meant to be kept rather they were buried in the ground to improve the harvest and health of crops, and formed part of various Slavic pre-Christian fertility practices.

Pysanky are made with blown eggs and decorated using wax-resist techniques and dye, similar to Batik. This video (3:39 mins) shows how a Pysanka is made.

A Ukranian legend says that as long as people continue making Pysanky, the world will continue to exist. According to this legend, an evil monster lives beneath the world and is restrained by chains. Every year, spies are sent out to see if anyone is making Pysanky for Easter. If they are, the chains around the monster are tightened, if not, the chains are loosened until the monster is released and destroys the world. Only women were allowed to make Pysanky and so the fate of the world rested on women’s shoulders.

This video (3:25 mins) below shows how the art of Pysanky is being used as an act of resistance against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

There are other styles of Easter egg decorating that are common throughout Eastern European and Slavic regions.

Krashanky are hard-boiled eggs that are dyed one colour and used to decorate Easter baskets for blessing before being eaten or buried in the ground as an offering for good harvests

Dryapanky are eggs dyed in one colour with symbols scratched onto their surface

Lystovky are dyed with small flowers or leaves to create a silhouette, similar to pace eggs described below

Krapanky uses the same wax resist technique as Pysanky but with wax dripped onto the egg in a spotted pattern without using symbols or drawing

Pace Eggs

Pace eggs (from the Latin root word for Easter or Passover, pascha), were traditionally wrapped in onion skins over flowers or leaves and boiled to give them a mottled-golden stain, leaving the flower or leaf pattern. Sometimes wax candles were used to write a person’s name and date before being stained. This custom was practiced in Britain and across Scandinavia. During the medieval period in Northern England these eggs were often given to performers of Pace Egg plays, which involved mock combat and singing. The Pace Egg plays largely died out in the 19th century after WWI but are being revived in places such as Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Here’s two or three jolly boys, all o' one mind,

We've come a pace-egging and I hope you’ll prove kind,

I hope you’ll prove kind, with your eggs and your beer,

For we'll come no more pace-egging until the next year.York Press - The history behind the Easter pace eggs at York’s Castle Museum

Ostereierbaum: The Easter Egg Tree

An old Easter tradition of decorating trees, tree branches or bushes with Easter eggs comes from Germany and is centuries old, though its origins have been lost. This custom is also found in Austria, Switzerland, Ukraine, Poland, Czech Republic, Moravia and the Pennsylvania Dutch region of the USA. The Saalfelder Ostereierbaum was an apple tree in the garden of Volker Kraft, in Thuringia, Germany, that was decorated with an increasing number of easter eggs every Easter from 1965 until 2015, with over 10,000 decorated eggs hung in 2012. However, the Guinness World Record for the largest number of Easter eggs on a tree was awarded to the Rostock Zoo in April 2007, which decorated a red oak with 79,596 blown and painted eggs.

It seems egg trees were not only used for Easter celebrations. In his book Ozark Magic and Folklore (2012) Vance Randolf noted that:

By all odds the most striking barrier against witches is the so-called egg tree. Usually it is just a little dead bush with the branches closely trimmed, and literally covered with carefully blown egg shells. There are hundreds of egg shells on a really fine egg tree, which often requires years to perfect. It is set firmly in the ground near the cabin, a favorite place being under a big cedar in the front yard. Just how the egg tree is supposed to drive off witches I was never able to learn.

Coloured pieces of eggshells were also used to decorate May Bushes for May Day (Beltaine), which we will explore in the next article.

Easter Egg Hunt

Throughout Europe, eggs were given as gifts on Easter Sunday and were an important part of celebrations, especially for poorer people who were not able to afford meat. They were such an important symbol for the season that even royal families gifted eggs. In 1290 AD, Edward I of England had 450 eggs decorated with coloured dyes, gilded with gold leaf and distributed to his household. Several years later, Henry VIII received a decorated egg in a silver case from the Vatican.

Scholars believe that the Easter egg hunt tradition originated in Germany. Eggs were believed to represent the resurrection of Jesus and Protestant reformer Martin Luther organised egg hunts, in which men hid the eggs and the women and children hunted them. The purpose of these hunts was to remind Luther’s congregation that the empty tomb of Jesus, represented by the egg, was discovered by women.

As mentioned in the previous episode, Episode 18 - Spring Equinox: Eostre, Easter, Witches and Bunnies, the white hare was thought to symbolise the Virgin Mary’s sexual purity. German Lutherans developed the story and tradition of the Osterhase or Easter Hare that hid coloured eggs, sweets and sometimes toys for ‘good’ children to find on Easter Sunday. We know this famous character as the Easter Bunny. Easter hunts were not known or practiced outside of Germany until the Victorian Era.

As a child the future Queen Victoria enjoyed egg hunts at Kensington Palace. These were put on by her mother, the German-born Duchess of Kent… Victoria and Albert continued this German tradition, hiding eggs for their own children to find on Maundy Thursday. Albert was responsible for hiding the eggs, concealing them in ‘little moss baskets’ and hiding them around the palace. Victoria made numerous references to these egg hunts in her journals.

Source: English-heritage.org.uk

Magazine articles such as the Illustrated London News described and helped to popularise the Easter egg hunt as a family tradition across Britain, while German immigrants helped to spread the tradition to the United States.

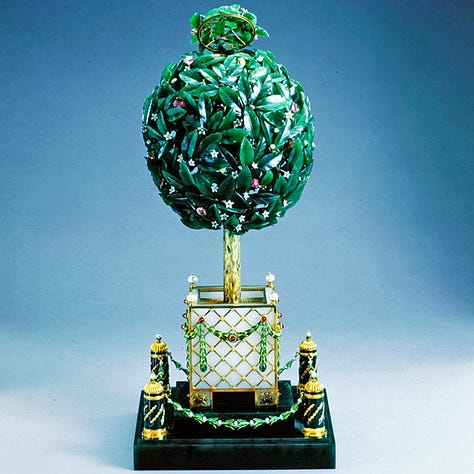

The most expensive Easter eggs ever made were made by Fabergé and created between 1885 and 1916 for the Russian Imperial family.

Created as gifts for the tsar’s wife and mother, each of Fabergé’s unbelievably lavish Imperial eggs opened to reveal a precious surprise. Of the 50 produced, the location of 43 is known. In 2014, the previously missing Third Imperial Egg, valued at $33 million, was recovered from an American flea market.

Source: SBS.com - The history of chocolate Easter eggs and other Easter traditions

Easter Games

There are a few popular Easter games that involve Easter eggs, which are still played throughout Europe and their old colonies. One of them is known as egg rolling and was first recorded in the 1790s in the north of Britain. Children gathered together to roll decorated eggs from the tops of grassy hills. Good luck and sometimes prizes were granted to those whose eggs reached the bottom first or went the longest without shattering. During the Edwardian period in England, large crowds gathered at the Penrith castle moat, Avenham Park in Preston, and Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh to watch the egg rolling. Easter egg rolling was also popular in Germany and German-speaking regions. The video (1:24 mins) below shows an Easter Egg Roll from 2017 at Devil’s Dyke in Sussex, Southern England.

Even the US White House has held an annual Easter Egg Roll since 1878. Entry for children and their parents is now allocated via a lottery system. As the White House Lawns are flat, the tradition has been slightly altered so that wooden spoons are used to roll the Easter eggs across racing lanes marked out on the South Lawn.

This video (2:27 mins) shows the fun activities involved in the White House’s Easter Egg Roll festivities from 2009.

Egg and spoon racing is also a popular Easter game. Raw eggs are balanced on silver spoons held in one hand (for children) and in the mouth (for older people) while racing each other. The first one to reach the other end without dropping and shattering their egg wins. Boiled eggs are often used for very young children so they have a fighting chance.

Finally, egg tapping is also commonly played across Europe at Easter. Depending on the region, raw or hard-boiled decorated Easter eggs are tapped together and the first one to crack or shatter loses, with good luck bestowed upon the winner.

Easter Food

Chocolate Eggs

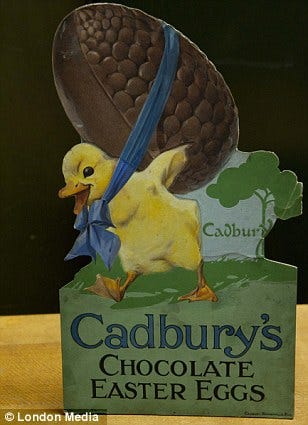

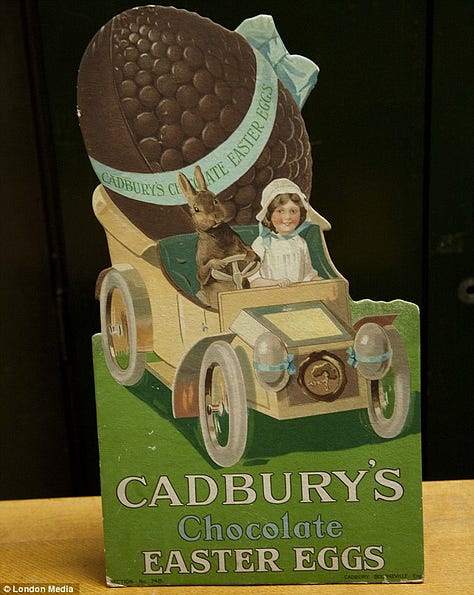

Solid chocolate Easter eggs were first manufactured in France and Germany in the early nineteenth century. During the Victorian era in England, cardboard and satin-covered eggs filled with chocolates and sweets were popular gifts.

It wasn’t until 1873, that English chocolate manufacturer J.S. Fry & Sons (which was eventually incorporated into the Cadbury empire) produced the first hollow chocolate egg using specialised egg moulds. Two years later, in 1875, Cadbury manufactured their first Easter egg after developing pure cocoa butter that could be poured and moulded into smooth shapes. They were made of dark chocolate and filled with sweets. These novelty eggs were expensive to produce as they were hollow and required specialised equipment and a laborious process to manufacture.

Sales of this type of chocolate Easter egg increased enormously but remained expensive luxury items until the 1950s. Advances in production and packaging reduced costs and meant that chocolate Easter eggs were now accessible to the masses. It was also during the 1950s that Easter egg marketing began to target children.

Easter Bread

Leavened bread forms an important part of traditional Easter food customs across Europe. They are often sweetened, dried fruit and citrus peel are sometimes added and decorations can include braiding the dough, dyed eggs, icing and sprinkles. These breads include the Greek Tsoureki, the Italian Pane di Pasqua, the Russian Kulich, and the German Osterbrot and there are many more types of Easter bread associated with different regions across Europe. Hot cross buns are the most popular Easter breads in English-speaking countries and we explore that tradition in the section below.

Hot Cross Buns

“Hot Cross Buns! Hot Cross Buns! One a penny, two a penny, Hot Cross Buns! If you haven’t got a daughter, give them to your sons. One a penny, two a penny Hot Cross Buns!”

Hot cross buns have a long and interesting history, perfectly summed up in the excerpt below from The Bread Baker’s Guild magazine “Breadlines” by Mitch Stamm and Kate Goodpaster:

Nations, cultures, and religions include bread as an integral component of religious and secular observances. The breads are typically enriched and may contain dairy, eggs, sweeteners, and inclusions. Hot cross buns have been synonymous with Easter celebrations since they appeared in 12th century England. Interestingly, hot cross buns pre-date Christianity, with their origins in paganism. Ancient Egyptians used small round breads topped with crosses to celebrate the gods. The cross divided the bread into four equal sections, representing the four phases of the moon and/or the four seasons, depending on the occasion. Later, Greeks and Romans offered similar sweetened rolls in tribute to Eos, the goddess of the morning, and to Eostre, the goddess of light, who lent her name to the Easter observances. The cross on top symbolized the horns of a sacrificial ox. The English word bun is a derivation of the Greek word for ceremonial cakes and breads, boun.

In the Middle Ages, home bakers marked their loaves with crosses before baking. They believed the cross would ensure a successful bake, warding off the evil spirits that inhibit the bread from rising. This superstition gradually faded, except for marking Good Friday loaves and hot cross buns, only to be replaced by another one. This time the loaves and buns were hung from the ceiling like sausages. It was believed that the bread would never mold (sic) and would provide protection against evil spirits and illness until the following Good Friday when the loaves and buns would be replaced. In the event of illness, a portion of bread could be removed from its string and crushed to a powder, which was incorporated into water for therapeutic effect. During the same period, Jews hung bread and a container of water from the ceiling to ward off cholera. They believed its power was so strong that one loaf in one house would protect the community. To avoid detection, early Christians celebrated the resurrection of Christ at the same time of year as the pagan Spring celebration.

It was in the 12th century that an English monk decorated his freshly baked buns with a cross on Good Friday, also known as the Day of the Cross. The custom gained traction, and over the years, fruits and precious spices were included to represent health and prosperity. Spiced buns were banned when the English broke ties with the Catholic Church in the 16th century. However, by 1592, Queen Elizabeth I relented and granted permission for commercial bakers to produce the buns for funerals, Christmas, and Easter. Otherwise, they could be baked in homes. The bakers argued that a cross cut into a loaf or bun induced a more pronounced rise in the oven: an axiom then, and an axiom now.

Farmers began to place hot cross buns in their stored grain to distract mice and other pests, much the way shoofly pie was used by American housewives. By the early 19th century, the Bun House of Chelsea, famous for Chelsea buns, was the largest producer of hot cross buns. It remained so for over a century until the building was demolished. Once an English specialty, the buns’ popularity has become a seasonal staple around the world and is included in Le Coupe du Monde de la Boulangerie as one of the Breads of the World.

Source: Ravenhook Bakehouse website - The Interesting Story of the Hot Cross Bun (2020)

Blessing of the Easter Food

Many Catholics and Orthodox Christians, particularly from Slavic regions and especially Poland, traditionally decorate and fill a basket of food to be blessed in church on Holy Saturday (the Saturday before Easter Sunday). These baskets are filled with foods that have religious symbolism and vary according to region but generally contain smoked meats, cheeses, sausage, butter, salt, Easter bread and decorated eggs. The butter or pastry is sometimes moulded in the shape of a lamb, representing Christ as the ‘Lamb of God’ as well as honouring the season of spring lambs. The baskets may also include a white candle representing Jesus, which is lit during the blessing.

In some churches or congregations, baskets are lined up on a long table and blessed by the minister/priest/parson/reverend, or parishioners carrying their baskets make their way in a line to the front of the church altar to receive their blessing. When the lenten fast is broken on Easter Sunday morning, the first food eaten is usually the blessed Easter eggs, which are cracked and shared around the table, before the rest of the food is eaten.

Celebrating Easter in the Southern Hemisphere

Spring Equinox celebrations in the Northern Hemisphere are closely aligned to the Christian Easter traditions. In the Southern Hemisphere, the Spring Equinox and Eostre celebrations occur on or near 22/23 September. Why not celebrate the next Spring Equinox with more seasonal traditions, incorporating your own belief systems and symbolism:

Decorate boiled or blown chicken, duck or goose eggs in whatever style takes your fancy, from the pysanky method to simply dying eggs in different colours

Decorate your home for Spring with cut flowers, decorated eggs, and images or statuettes of hares, eggs, nests and lambs

Create your own Haft-Sin table with ornaments and items that have special significance for you, your personal spiritual or religious beliefs and the season of Spring

Alternatively, create your own Easter basket full of delicious food for a blessing according to your beliefs or religion, then enjoy a feast

Organise an Easter egg hunt

Play Easter egg games

Make and eat Easter food such as Easter bread

Go all out and celebrate a garden party with friends and family

decorate your house and garden for the season

organise games - Easter egg-based, as well as other garden games such as croquet, boules sport (lawn bowls, French pétanque, Italian bocce), lawn darks, horse-shoes or quoits etc

have an Easter egg hunt

make and eat traditional Easter food and or a high tea (you can always share the load by asking guests to bring a plate)

ask guests to bring an Easter basket full of their favourite foods that represent spring

In next week’s episode, we will explore how the upcoming celebration of Halloween is actually the season for celebrating Beltaine in the Southern Hemisphere, and we’ll take a deep dive into the history and traditions of Beltaine. In the meantime, please subscribe if you haven’t already and leave a comment below on how you celebrate Spring or let me know about your Easter traditions.

Share this post