Welcome to Episode 2 of the Wheel & Cross podcast, where we’re celebrating the first day of winter with Holle’s Day.

June 1 marks the first day of winter in Australia. In the more southerly states, winter is a time when the world undergoes a profound transformation, as nature withdraws into a state of hibernation and stillness. The air becomes crisp and cold, and on clear mornings the landscape sparkles with frost or snow, punctuated by bare-branched trees or evergreens. Winter evokes a sense of introspection, inviting individuals to turn their attention inward, reflect on the passing year, and embrace the slower pace of life.

It is also a season of cosy warmth, where people gather around crackling fires, sip hot beverages, and seek comfort in the company of loved ones. Winter holds opportunities for celebration and festivities, holidays and traditions that bring families and communities together. It is a time when humans adapt to the challenges of the season, finding joy in the beauty of icy landscapes, the thrill of winter sports, and the anticipation of new beginnings as they await the arrival of spring.

According to the Ngunnawal knowledge keepers and traditional custodians of the place I call home, this is the start of deep winter, the second half of the season of Magarawangga. This season is marked by heavy fog and frosts that will last until July, with snow dusting the tops of the Brindabella Ranges and deepening in the Australian Alps, the Snowy Mountains. As winter sets in, early flowering wattles will start to bloom yellow and will be joined by the Spring-flowering wattles until they reach their climax in September. It’s breeding time for echidnas, and the lucky observer may be able to spy the charming sight of an echidna love train as males doggedly court their chosen female in a most gentlemanly fashion.

In Germanic regions of Europe, and in my own household, the first day of winter is marked by the celebration of Holle’s Day, one of the many depictions of the winter witch or queen that are found throughout most of Europe.

In this episode we will explore the various depictions of the winter witch or queen, including the Germanic Frau Holle, also known as Holda, and Perchta. We will also learn about Cailleach the Celtic winter hag, Skaði the Norse goddess of winter, Baba Yaga and Morana, the Slavic winter witches, and explore depictions of the Snow Queen in modern literature and popular culture.

We will then dive into the folklore of the kings of frost and snow including Jack Frost, Old Man Winter, and the modern winter icon of Frosty the Snowman. Finally, we’ll end this episode by exploring the modern Danish concept of Hygge.

Winter Queens

Revered in cultures across the globe the Winter Queen reigns over wintry landscapes of frost, ice, and snow, embodying the power and magic of the winter season. Among these timeless Winter Queens often also called witches, we encounter the ancient and awe-inspiring Cailleach from the Celtic lands, the kind but strict Frau Holle or Holda and the fearsome Perchta from the Germanic regions, the strong-willed Skaði from Norse mythology, as well as the enigmatic witch Baba Yaga, and the beautiful but deadly Morana from the Slavic countries of Eastern Europe.

Frau Holle

Frau Holle, also known as Holda or Mother Hulda, is a legendary figure in German folklore associated with the winter season. She is often depicted as an elderly woman who lives at the bottom of a well or in a remote house on a mountain. Frau Holle is closely connected to the changing of the seasons and is said to govern the weather and the fertility of the land.

According to German folklore, Frau Holle shakes out her featherbeds or pillows, which causes snow to fall on Earth, marking the arrival of winter. She is seen as both a benevolent and strict figure, rewarding hard work and kindness while punishing laziness and rudeness. It is said that those who show respect and kindness to her are blessed with good fortune, while those who mistreat her or neglect their responsibilities may face her wrath.

In some folktales, Frau Holle flies across the skies during winter on a heavenly sleigh or chariot blessing the farmland below. Some places in Germany, particularly rural areas, traditionally placed eggs and dumplings on the rooftops of houses to honour Holle on her journey, in return for good fortune. Other places laid out sweetened bread, fruit cakes, pastries, tarts and strudels on special feasting tables.

Frau Holle is also associated with spinning and weaving. Some say that she spins the clouds and weaves the fabric of the weather. She is also often depicted with a distaff, an ancient tool used in spinning, and is said to fly on them, leading women on journeys across the countryside, to great feasts or into battle against evil spirits. Records show women used hallucinogenic mixtures, colloquially called flying ointments, for shamanic journeying, going…

“out through closed doors in the silence of the night, leaving their sleeping husbands behind”¹

As Christianity spread throughout Germany, these journeys became linked to witchcraft and as distaffs disappeared from use, they evolved into brooms.

The tale of Frau Holle was first collected and published in 1812 by the Brothers Grim in their book, Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). It was also included in the 1890 anthology of fairy tales titled, The Red Fairy Book, compiled by Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang. An echo of Frau Holle can be found in the British Children’s Nursery Rhyme, ‘There Was an Old Woman’.

There was an old woman tossed up in a basket,

Seventeen times as high as the moon;

Where she was going I couldn’t but ask it,

For in her hand she carried a broom.

Old woman, old woman, old woman said I,

Where are you going to, up so high?

To brush the cobwebs off the sky!

May I go with you? Aye, by-and-by.

Perchta

Perchta, also known as Berchta or Frau Perchta, is another mythical figure from Germanic folklore associated with the winter season. She is often depicted as a fearsome and powerful woman, both beautiful and terrifying. Perchta is believed to wander the Earth from December 25th to January 6th, through the Northern hemisphere’s Christmas or Yule season, overseeing the behaviour of people and the cleanliness of their homes. At this time of year, people would leave offerings of food for Perchta, such as bread or porridge, to ensure her favour and protection. She is often celebrated in winter festivals, where her presence is acknowledged through songs, dances, and other folk customs.

Similar to Frau Holle, Perchta is associated with both the reward of good deeds and the punishment of misdeeds. However, her wrath for those who have been lazy, selfish, or dishonest is generally rather more violent, with gory consequences, including the slitting of bellies and stuffing of the empty cavity with hay. She is particularly known for her focus on spinning and weaving, and those who neglect their spinning during the winter season may find their spindles tangled or their thread cut as a sign of her disapproval… if she is feeling benevolent. In some traditions, Perchta is believed to have the ability to transform into a beautiful white swan or a haggard old woman. She is associated with the concept of duality, representing the transition between life and death, light and darkness, and the changing seasons.

While Perchta is primarily associated with the Twelve Nights and the Winter Solstice, there is a fascinating connection between her and the Wild Hunt in some folklore traditions. The Wild Hunt is a mythological event in which a spectral group of hunters, often led by a supernatural figure, rides through the night sky or across the land. In certain regions of Central Europe, including Germany and Austria, Perchta is believed to be the leader of the Wild Hunt during the winter season. She is said to ride through the night with her followers, which may include spirits of the dead or other supernatural beings, creating an awe-inspiring and often terrifying spectacle.

Cailleach

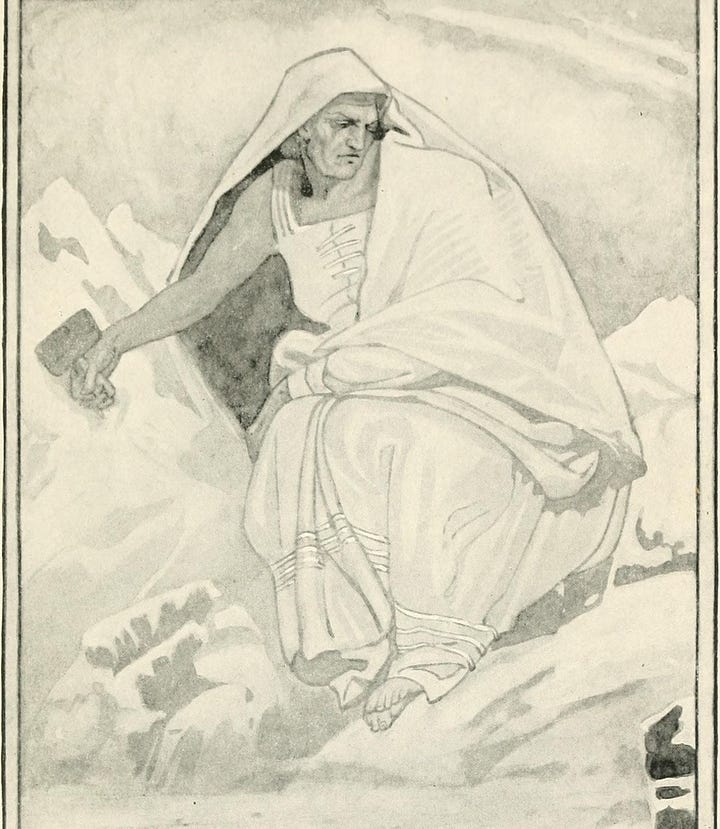

Cailleach, also known as Cailleach Beira, is an ancient Celtic goddess associated with winter, mountains, and sovereignty over the land. She is often described as a divine hag or crone, symbolising wisdom, power, and the cyclical nature of life. The Cailleach’s presence is strongly felt during the winter months when she is said to rule over the harsh and barren landscape. She is believed to control the seasons by striking the ground with her staff, which brings about freezing temperatures and the and the onset of winter.

Donald MacKenzie described Cailleach in his book, Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life, (MacKenzie, 2010), first published in 1935:

…her face was blue-black, of the luster of coal,

And her bone tufted tooth was like rusted bone.

In her head was one deep pool-like eye,

Swifter than a star in winter.

Upon her head gnarled brushwood,

like the clawed old wood of the aspen root.

In Scottish and Irish folklore, Cailleach is associated with specific geographical features, particularly mountains, and rocky outcrops. It is said that she formed these landscapes by dropping stones from her apron, smashing them with her hammer or hurling boulders during her battles with other divine figures. On the west coast of Scotland, it is said that Cailleach brings in the winter by washing her great plaid cloak in the sea for three days until it is pure white, forming the Corryvreckan whirlpool (cauldron of the plaid) and then placing her pure white plaid on the mountains to dry, covering them in cloud and the land in snow. Legend has it that while she is washing her plaid, the roar of the coming winter tempest can be heard as far as twenty miles inland.

Other tales describe Cailleach gathering her firewood on the eve of the winter solstice, preparing for the longest night of the year. In some stories, Cailleach drinks from the well of life on the morning of the winter solstice. Her life force is renewed by the water, and she transforms from an old crone into a beautiful maiden, often represented by Bride or Brigid, the Celtic goddess of light, life, rebirth, and spring.

Another version tells that it was Bride who sought to bring about the return of the sun and the revitalisation of the land. In her quest, she encounters Cailleach and requests access to the well. Cailleach, in her role as the guardian of winter and the old year, initially refuses Bride’s plea. However, Bride who is also known for her wisdom and craft, uses her persuasive powers and offers Cailleach gifts in exchange for a drink from the sacred well. Eventually Cailleach relents and allows Bride to drink from the well. As she drinks, Bride absorbs the essence of the winter solstice, gaining the strength to challenge and overcome Cailleach’s dominion over darkness and cold.

While Cailleach is often portrayed as a formidable and solitary figure, she is also credited with nurturing and protecting wildlife. In some tales, she is said to provide food and shelter for animals during the harsh winter months.

Interestingly, some scholars argue that there is a close connection between Cailleach and the Hindu Goddess Kali, both being representations of an even older, paleolithic Great Mother, linking these ancient cultures across vast distances and time. As humans migrated from India to Europe during the Neolithic period, they carried with them the collective memories and symbolism associated with the primordial divine feminine. This migration facilitated the transmission of cultural beliefs and mythologies, including reverence for the Great Mother archetype. The commonalities observed in the representations of these powerful female deities suggest a shared ancestral lineage rooted in the Paleolithic era, many thousands of years ago.

Skaði

Skaði, also known as Skadhi, is a figure from Norse mythology associated with winter, mountains, skiing, and hunting. She is a giantess or jötunn and is often depicted as a powerful and fierce warrior. Skaði is the daughter of the giant Thiazi and becomes a significant figure in the Norse pantheon through her marriage to the god Njord.

Skaði’s story is rooted in revenge and a desire for justice. Her father was killed by the gods, and she sought retribution. As compensation, the gods offered her a husband of her choice from their ranks, as well as the ability to choose her own dwelling. Skaði chose Njord, the god of the sea and abundance, but their contrasting natures and preferences eventually led to their separation.

Skaði is closely associated with the winter season, embodying its harshness, coldness, and challenges. She is often depicted in winter attire, wearing furs and carrying a bow and arrows. Skaði is known for her skill in skiing and hunting, and she is considered the patron of winter sports and activities. Her presence is believed to bring snowfall, icy winds, and the stillness of frozen landscapes. She is also a goddess of mountains and wilderness.

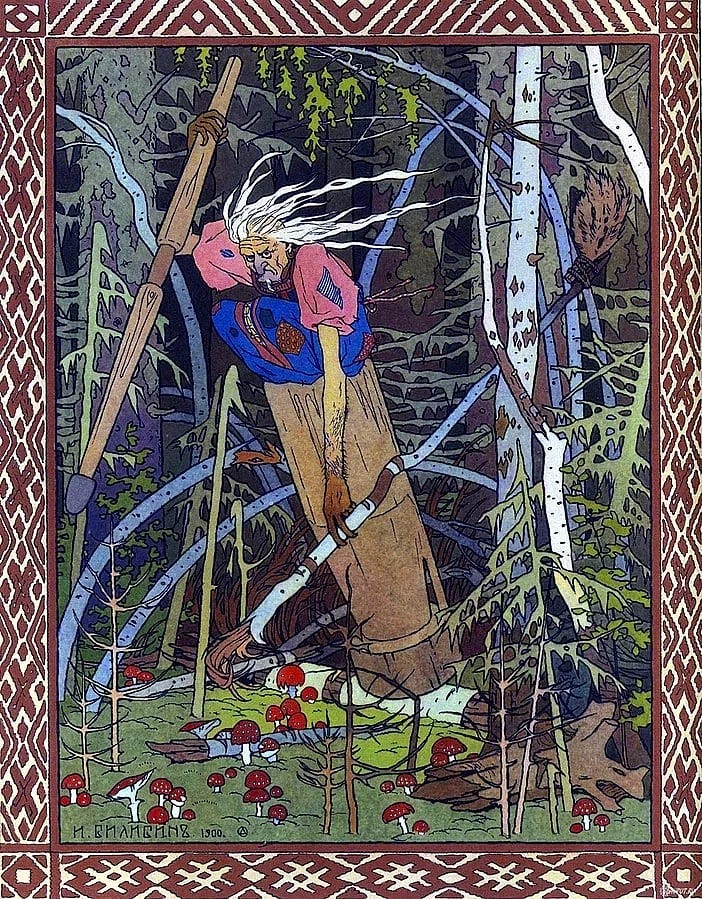

Baba Yaga

Baba Yaga is a prominent figure in the Slavic folklore of Eastern Europe. Although not exclusively associated with winter, she is often depicted as an ugly but mysterious and powerful old woman, living deep in the forest in a hut that stands on chicken legs with her garden fence and gate made from the bones of the children that she has eaten. She flies through the air in a mortar, using its pestle as a rudder. Baba Yaga is known for her enigmatic nature, her cruelty, her wisdom, and her connection to magic and the supernatural.

Baba Yaga’s portrayal in folklore varies, and she can take on different roles and meanings depending on the story. She is sometimes depicted as a fearsome witch, a devourer of children, a guardian of the forest, or a wise crone who imparts valuable knowledge and guidance to those who seek her out. Her depictions as a child eater may come from the ancient Slavic midwifery practice of rolling sick or weak newborns in dough and placing them near or in the household oven, an early version of our modern incubator.

In some versions of her story, Baba Yaga is associated with winter. She is believed to possess the ability to control the weather, bringing cold winds, snowstorms, and frost. She is often portrayed as an unpredictable force of nature, capable of both benevolent and malevolent actions.

Morana

Morana, also called Marzanna, is a Slavic goddess associated with winter, death, and rebirth (Hirst, 2019). In Slavic mythology, she is often depicted as a beautiful but stern woman with long, flowing black hair and dressed in white or black garments. Morana represents the cold, dark months of winter and the dormant period of nature. As the goddess of winter, Morana is both feared and respected. She is believed to bring frost and cold winds. In some traditions, Morana is seen as the personification of death itself, ruling over the realm of the dead during the winter months.

However, Morana is not solely associated with death and darkness. She also symbolizes the cyclical nature of life and the promise of rebirth. In Slavic folklore, it is believed that Morana’s departure marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring. Various customs celebrated in early spring often involve a ritual sacrifice of Morana’s effigy through drowning or burning, to ensure the renewal and awakening of nature.

We will explore the specific traditions related to Morana and the season of Spring in a future article. Watch this (4:56 mins) YouTube video for more interesting information about Morana.

The Snow Queen and Winter Witch

The allure of the Winter Queen extends beyond folklore and mythology. The figure of the Snow Queen or Winter Witch appears in literature and popular culture, from Hans Christian Andersen’s mesmerising tale of The Snow Queen to the chilling White Witch in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, to Elsa, the icy queen from Disney’s movie Frozen, and the Finnish-turned-Japanese cult classic Moomin and the Lady of the Cold.

Andersen’s beloved fairy tale, The Snow Queen, centres around an icy and emotionless Queen, who captures young Kai and draws him away from his dear friend Gerda, into her frozen realm where Kai forgets who he is. Gerda embarks on a journey through the seasons and into the land of winter, to find her friend Kai and break the curse laid upon him. The story of The Snow Queen has been published many times, in folktale compendiums or in illustrated children’s books, and was adapted into a 2012 Russian-made animated movie with the same title.

C. J. Lewis published the first book in his seven-part fantasy series, The Chronicles of Narnia, in 1950. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe features a formidable sorceress called the White Witch, who casts a perpetual winter over the land on Narnia. Her icy presence instils fear in the hearts of Narnians, and it is up to the Pevensie children and the mighty lion Aslan to free the land from her icy grip. The book is still in print, with many different editions and was adapted into a movie in 2005.

Then there is Elsa, the young snow queen from Disney’s 2013 animated masterpiece, the ever popular Frozen. With her icy powers and the iconic anthem Let It Go, Elsa has become a symbol of empowerment, sisterhood, love, self-discovery and embracing our true selves, even the cold and dark parts.

Frozen II was released in 2019 and focuses on Elsa’s quest to secure the future of her people by discovering her past. It features folklore, and customs of the Saami people, an ancient culture from the northern-most parts of Europe and Asia, whose customs and lores have survived from the ice ages. We will explore the folklore and customs of the Saami people in the following chapter on Mother’s Night and the Winter Solstice.

Finally, there’s the Lady of the Cold from the Finnish cartoon cult classic, Moomin. The Moomins are a beloved series of characters invented by Finnish writer and artist Tove Jansson who created the original Moomin comic strips and books in the mid-20th century. Over the years, the Moomin cartoons have gone through various adaptations and interpretations. Notably, in the 1990s, a new Moomin animated series was produced by a Finnish-Japanese-Dutch collaboration. This series, known as the Moomin TV series, became particularly popular and helped introduce the Moomins to a new generation of fans worldwide.

The Moomin world, Moominland, has its own seasonal folktales and traditions, including the Lady of the Cold, who brings winter to the land as she rides through Moominvalley on her horse made of snow, freezing anyone who looks into her eyes. Jansson did not illustrate the Lady of the Cold character in order to make her seem more enigmatic, but she is depicted in several of the animated cartoon adaptations, including the Moomin TV series no. 26, The Lady of the Cold (4:57 mins):

The Japanese anime series Tanoshii Mūmin Ikka (3:19 mins):

As well as in the 3D animated series remake, Moominvalley (5:05 mins):

Kings of Frost and Snow

Just as many European cultures venerated or depicted winter in its feminine form, winter was also depicted in various masculine forms. There’s the young and mischievous Jack Frost, who paints delicate frost patterns on windowpanes and leaves a chill in the air wherever he roams. At the other end of the age spectrum is the venerable Old Man Winter, a figure steeped in mythology, including the formidable Nordic god Ullr, the frosty deities of ancient Rome and Greece, and the enigmatic Slavic legend of Ded Moroz. Finally, there’s the modern icon of winter, the whimsical Frosty the Snowman.

Jack Frost

Jack Frost is a mischievous and elusive character. He is said to be responsible for the frosty patterns that appear on windows and the delicate ice crystals that adorn plants and surfaces during cold winter nights. He is commonly depicted as a sprite-like figure, and sometimes as a small, slender man with icy blue skin or a white, frost-covered creature, often portrayed wearing a pointed hat and a coat made of frost. Jack Frost is known for his playful and mischievous nature, darting through the wintry landscape, leaving a trail of frost and icy breath behind him, sometimes causing trouble as he goes.

It is likely that Jack Frost originated from Anglo-Saxon and Norse folktales about Old Man Winter. However, this frost-charmed character first appeared in literature in 1734, in the pamphlet book, Round About Our Coal Fire, or Christmas Entertainments. He was later featured in a poem by 19th-century writer Hannah Flagg Gould, called The Frost, which depicted Jack Frost as a peaceful and artistic character who paints icy pictures on windows and makes a small bit of mischief along the way.

The Frost

The Frost looked forth, one still, clear night,

And he said, “Now I shall be out of sight;

So through the valley and over the height

In silence I’ll make my way.

I will not go like that blustering train,

The wind and the snow, the hail and the rain,

Who make so much bustle and noise in vain,

But I’ll be as busy as they!”

Then he went to the mountain, and powdered its crest,

He climbed up the trees, and their boughs he dressed

With diamonds and pearls, and over the breast

Of the quivering lake he spread

A coat of mail, that it need not fear

The downward point of many a spear

That he hung on its margin, far and near,

Where a rock could rear its head.

He went to the windows of those who slept,

And over each pane like a fairy crept;

Wherever he breathed, wherever he stepped,

By the light of the moon were seen

Most beautiful things. There were flowers and trees,

There were bevies of birds and swarms of bees,

There were cities, thrones, temples, and towers, and these

All pictured in silver sheen!

But he did one thing that was hardly fair, -

He peeped in the cupboard, and, finding there

That all had forgotten for him to prepare, -

“Now, just to set them a-thinking,

I’ll bite this basket of fruit,” said he;

“This costly pitcher I’ll burst in three,

And the glass of water they’ve left for me

Shall ‘tchick!’ to tell them I’m drinking.”

In 1874 Margaret T. Canby published the book, Birdie and His Fairy Friends, which featured a short story titled The Frost Fairies. This story depicts Jack Frost as the kindly king of the Winter Spirits who helps children escape from the cruelty of the neighbouring King Winter. Charles Sangster published a story in The Aldine magazine in 1875 (Vol.7, №16), called Little Jack Frost, in which Jack Frost is depicted as a mischievous but harmless being that nips people’s noses and coats the landscape in the snow before Dame Nature chases him away for spring. Scottish poet and author, Thomas Nicoll Hepburn, who also wrote under the pseudonym Gabriel Setoun, wrote one of the more well-known poems about Jack Frost in the late 1800s.

Jack Frost

The door was shut, as doors should be,

Before you went to bed last night;

Yet Jack Frost has got in, you see,

And left your window silver white.

He must have waited till you slept;

And not a single word he spoke,

But pencilled o’er the panes and crept

Away again before you woke.

And now you cannot see the hills

Nor fields that stretch beyond the lane;

But there are fairer things than these

His fingers traced on every pane.

Rocks and castles towering high;

Hills and dales, and streams and fields;

And knights in armor riding by,

With nodding plumes and shining shields.

And here are little boats, and there

Big ships with sails spread to the breeze;

And yonder, palm trees waving fair

On islands set in silver seas,

And butterflies with gauzy wings;

And herds of cows and flocks of sheep;

And fruit and flowers and all the things

You see when you are sound asleep.

For, creeping softly underneath

The door when all the lights are out,

Jack Frost takes every breath you breathe,

And knows the things you think about.

He paints them on the window-pane

In fairy lines with frozen steam;

And when you wake you see again

The lovely things you saw in dream.

L. Frank Baum also wrote several stories featuring Jack Frost. The book, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, published in 1902, features Jack Frost, son of the Frost King who enjoys nipping people’s noses, ears, and toes. Santa Claus asks Jack to spare the children, and Jack agrees “if he can resist the temptation.” In another short story by Baum, the same Jack Frost character has the power to freeze shadows and separate them from their owners, making them into their own entities.

Jack Frost also appears in a more contemporary novel, Terry Pratchett’s The Hogfather, published in 1996 and the 20th book in his Discworld series. In the novel, Jack grows tired of painting fern patterns and begins to paint more elaborate pictures on windows.

Jack Frost also became a popular icon in animated movies. In 1934, Ub Iwerks produced an animated short film about Jack Frost as part of its ComiColor cartoon series, in which Jack Frost warns the creatures of the forest about Old Man Winter while he paints the landscape in autumnal colours.

Ranking/Bass Productions produced a stop motion animated TV Christmas Special titled Jack Frost, which first aired on NBC in December 1979 and tells the tale of Jack Frost and his adventures as a human. Warner Bros. re-released the special in 2008.

In 2012, children’s film writer and producer, William Joyce released the animated film Rise of the Guardians, which features Jack Frost with his own origin story. Joyce also published a children’s picture book about Jack Frost in 2015 as part of his Guardians of Childhood series, with a slightly different origin story to the movie. Jack Frost has also starred in several Hollywood B-grade movies and even a horror movie titled Jack Frost, which was released in 1997.

Old Man Winter

Old Man Winter, like Jack Frost, is another prominent figure in folklore associated with the winter season. He is seen as the personification of the harsh and cold winter and is often portrayed as an elderly man with a flowing white beard who blows winter over the landscape with his breath or simply freezes the landscape with his presence.

Although winter was frequently associated with winter goddesses in the myths of the ancient Celts, and indigenous populations of Northern Europe, in the Nordic pantheon, the god Ullr (or Oller) is said to represent winter alongside the goddess Skaði who we have previously discussed. According to the Poetic Eddas, Ullr ruled over Asgard and Midgard during the winter months and was banished from Midgard during the summer months when Odin, as the god of summer, claimed kingship.

Some scholars assert that Ullr was one of the oldest gods of the Vanir, whose importance waned by the time the northern parts of Norway were settled. He may be related to Skaði and is even now considered the Guardian Patron Saint of Skiers. A medallion depicting Ullr, wearing skis and holding a bow and arrow is commonly worn as a talisman by ski patrols, as well as recreational and professional skiers throughout Europe’s alpine regions during the winter ski season.

In Scottish folklore, there is a similar figure known as Old Man Winter or Old Jack Frost. He is described as an elderly man with a long white beard, dressed in tattered winter garments. He brings the frost and snow, covering the land with a wintry blanket. Legends often tell of encounters with Old Man Winter during snowy nights, where he bestows blessings upon those who show kindness and hospitality.

The ancient Romans also influenced folklore in northern and western Europe. Winter was represented by the Roman god Aquilo or Septentrio. Aquilo was the Roman god of the northeast wind associated with winter, cold, and storms. He was also sometimes known as Septentrio, which refers to the seven (septem) stars that form the Plow or Big Dipper constellation. Similarly, the ancient Greeks called their god of the northeast winter wind Boreas, who was depicted as an old man with shaggy hair and a long beard, wearing a billowing cloak and holding a conch shell. He was said to be very strong and had a violent temper to match.

In Slavic or Eastern European folklore, Old Man Winter is known as Ded Moroz, or Morozko, which directly translates to Grandfather Frost. In modern Russia, Ded Moroz has evolved into a figure similar to Saint Nicholas, Father Christmas and Santa Claus, though he delivers presents to children for Russia’s New Year holiday, Novy God. We will learn more about the jolly figure of Ded Moroz and his granddaughter, the Snow Maiden Snegurochka, later on in the year, closer to the Christmas season. For now, his origins pre-date Christianity. According to some scholars of Slavic mythology, Ded Moroz was a Slavic winter wizard, or a snow demon. Before the Christianisation of the Rus, the term ‘demon’ did not have its current negative connotations. ‘Demon’ merely indicated that the character was an elemental force of nature rather than a human or a god.

Frosty the Snowman

Frosty the Snowman is a beloved and iconic character that has become synonymous with the winter season. The origin of Frosty the Snowman can be attributed to the song of the same name, “Frosty the Snowman,” written by Walter “Jack” Rollins and Steve Nelson. The song was first recorded by Gene Autry and the Cass County Boys in 1950 and was an instant hit. It tells the enchanting story of a snowman who comes to life with the help of a magical hat and embarks on adventures with children. The song was covered soon after its release by Jimmy Durante and Nat King Cole, whose versions also became well-loved hits.

That same year, Little Golden Books published a children’s book titled Frosty the Snow Man, adapted by Annie North Bedford and illustrated by Corinne Malvern. In 1955, UPA studio released a black and white animated short of Frosty the Snow Man, which is still played on American TV stations during the winter holiday season.

Following the success of the song, Frosty the Snowman was adapted into a 25-minute animated television special in 1969. The animated special, produced by Rankin/Bass Productions, follows the story of a group of children who build a snowman named Frosty and witness his magical transformation into a lively and joyful character.

Three sequels followed:

Frosty’s Winter Wonderland in 1976, based on the song Winter Wonderland

Rudolf and Frosty’s Christmas in July, released in 1979, and

The Legend of Frosty the Snowman, released in 2005.

Since then, Frosty the Snowman has become an enduring symbol of winter and the holiday season. The character has appeared in numerous adaptations, including books, films, and merchandise.

Hygge

As we look towards the colder and darker time of year, the Danish concept of hygge provides some comfort and a sense of cosiness and contentment by creating a bulwark against winter and inclement weather. According to Meik Wiking, author of ‘The Little Book of Hygge: The Danish Way to Live Well’, hygge is a concept deeply rooted in Danish culture and has evolved over centuries as a way of life. The Danish word hygge, roughly translates to cosiness, comfort, a feeling of contentment, warmth and togetherness. It is the root word for hug and emerged as a response to the long dark winters that Denmark experiences, where creating a warm and inviting atmosphere became essential for well-being.

The Danish people embrace hygge as a way to find joy and happiness in simple pleasures, fostering a sense of togetherness and cultivating a cosy ambience in their homes. This is done by transforming indoor spaces into inviting sanctuaries, adorned with soft lighting, flickering candles, and plush pillows and blankets. It involves sipping warming beverages like hot cocoa or mulled wine, savouring comforting dishes that nourish the body and soul, and engaging in activities that cultivate a cosy atmosphere and promote relaxation: sitting by a crackling fire, reading a book, playing board games, sharing meals and easy conversation with friends. It can even mean finding a sense of peace and calm by donning warm clothes and footwear, and walking in nature, absorbing the beauty of the winter landscape.

Denmark has consistently been rated as the first or second happiest country in the world². According to Meik Wiking, who is also the CEO of the Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen, this is largely because of hygge, a cultural phenomenon that focuses on the small things that really matter, quality time with friends and family, and the enjoyment of the good things in life, especially during the darkest time of the year³.

Winter is a joyful time for me as I wholeheartedly embrace the art of hygge. When the winter chill deepens, when frosts turn the ground into a carpet of sparkling diamonds, when fogs roll in that last until the afternoon, and especially as icy storms rage and darkness increases, my home becomes a hyggelig cosy nest, filled with candles, soft lighting, warm throws and a crackling fire. There’s hot cocoa and warm spiced apple juice, freshly made popcorn, soups and slow-cooked meals to warm and nourish my family.

I also love to decorate for the season, and on the 1st of June, in celebration of the first day of winter, Holle’s Day in my household, the autumnal decorations come down, replaced by my winter decorations. Crystal snowflakes and winter-themed ornaments are hung on my bare-branched decorative tree, figurines and images of snowmen adorn spare surfaces, along with white polar bears and other snowy animals. Graceful statues of reindeer are also displayed, in anticipation of the coming winter solstice and mother’s night.

I hope you enjoyed today’s article about Holle’s Day, the winter queens, kings of frost and snow and the art of Hygge. Next week we’ll explore the ancient histories, traditions and folklore of the winter solstice and the celebration of Mother’s Night.

[1] From the 10th century Canon Episcopi, quoted by Carlo Ginsburg (1990). Ecstasies: Deciphering the witches’ sabbath. London: Hutchinson Radius.

[2] Helliwell et al., 2021; World Population in Review, 2021

[3] Meik Wiking (2016). The Little Book of Hygge: The Danish Way to Live Well.

Share this post