Dear Readers,

I hope you are enjoying the countdown to Christmas wherever you are. Many of you in the northern hemisphere will be heading towards the depths of winter and the winter solstice, while many of us Antipodeans are looking forward to Christmas in the middle of our hot summer. It was fun to share the joy of an Aussie Christmas with you last week. This week, in anticipation of a visit from the main man of the season (Santa Claus), we’re going to dive into the fascinating history and traditions of Santa’s ‘helpers’.

Thanks to Christmas movies, Christmas cards, illustrations and modern-day folk tales about Santa Claus, Santa’s helpers are usually depicted as jolly little elves who assist Santa in making and wrapping children’s toys at their home in the North Pole. However, in mainland Europe, Santa’s helpers are less convivial and some are sinister or even downright terrifying. Let’s take a look at the history of Santa’s elves, from the nice to the ‘not so nice’.

Enjoy!

Santa’s Christmas Elves

The video (6:40 mins) above features a vintage Walt Disney short film from 1932, Santa’s Workshop, about Santa and his little helpers preparing for Christmas. Santa’s elves are depicted as small, jolly and industrious pixie-like creatures, with pointy ears, long beards and pointy hats. They are responsible for making and wrapping toys in Santa’s workshop and for taking care of Santa’s reindeer. But, where did this idea of Santa’s jolly and helpful elves come from, considering that elves from the older European traditions are much darker and some are downright terrifying?

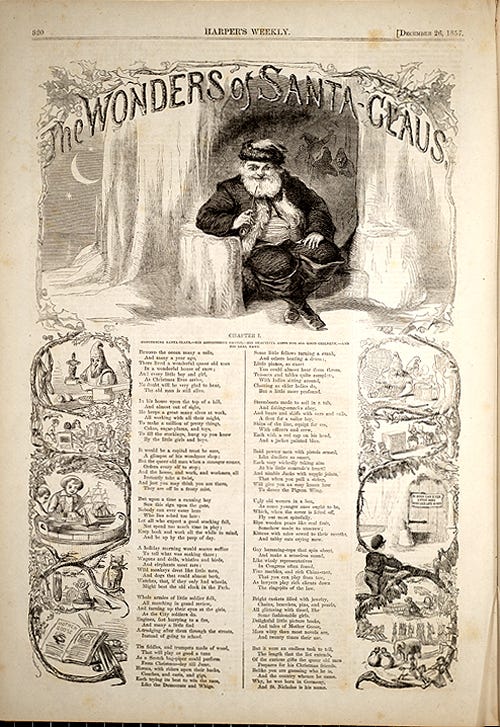

Although Santa Claus has ancient ties to Christmas, as we shall see in next week’s episode, the Christmas elves are a much more recent entity. They first appeared in a book by American author Louisa May Alcott in 1855. Louisa wrote the much-loved novel Little Women (1868) but her book, Christmas Elves, was never published. Two years later Harper’s Weekly published an anonymous poem, The Wonders of Santa Claus, which describes the elves:

Beyond the ocean many a mile,

And many a year ago,

There lived a wonderful queer old men

In a wonderful house of snow;

And every little boy and girl,

As Christmas Eves arrive,

No doubt will be very glad to hear,

The old man is still alive.In his house upon the top of a hill,

And almost out of sight,

He keeps a great many elves at work,

All working with all their might,

To make a million of pretty things,

Cakes, sugar-plums, and toys,

To fill the stockings, hung up you know

By the little girls and boys.It would be a capital treat be sure,

A glimpse of his wondrous ‘shop;

But the queer old man when a stranger comes,

Orders every elf to stop;

And the house, and work, and workmen all

Instantly take a twist,

And just you may think you are there,

They are off in a frosty mist.

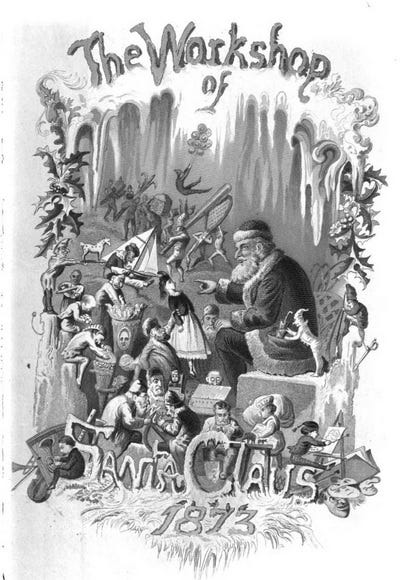

In 1873, the front cover of the widely circulated American magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book, showed an engraving of Santa directing his elves while they made toys, with the caption: “Here we have an idea of preparations that are made to supply the young folks with toys at Christmas time.”

Santa’s elves were included in an influential play written by Austin Thompson in 1876, called The House of Santa Claus, a Christmas Fairy Show for Sunday Schools. By the end of the 1800s, Santa and his elves were firmly established in the popular imagination. In 1922, Norman Rockwell famously painted Santa including his industrious elves for the cover of the American publication, Saturday Evening Post.

Inspiration for Santa’s elves likely came from the Scandinavian Yule traditions of immigrant families in America. Before St. Nicholas or Santa became popular in Sweden, gifts were given at Yuletide by the Julbok (Yule Goat), which we explored in a previous episode, Episode 9 - Scandinavian Yule Creatures. This gift-giving characteristic shifted in the 1800s to the Tomte/Nisse, a popular pixie-like entity, which protected farms, homesteads and familial houses (explored in the same episode above). It’s easy to see how the bearded little folk with red-pointy hats, long white beards and big noses inspired the depiction of Santa’s elves, though they are popular Yuletide characters in their own right.

As folktales often do, the story of Santa’s elves has evolved and now we find that, according to the internet, Santa has six official elves, each responsible for different tasks. No source material can be found for these names but their propagation across the internet is interesting nonetheless. Meet the six official Santa’s Elves as compiled by Manimal Tales:

Alabaster Snowball: Alabaster is the administrator of Santa’s (in)famous Naughty and Nice List. You definitely want to make sure you’re always nice to him!

Bushy Evergreen: Bushy is the inventor of the magic toy-making machine Santa uses to produce all the toys that are sent to kids all over the world.

Pepper Minstix: Pepper is the protector of Santa’s secret village near the North Pole. Think of him as Head of Elf Security.

Shinny Upatree: Shinny is Santa’s oldest friend and co-founder of Santa’s secret village and workshop.

Sugarplum Mary (aka Mary Christmas): Mary is in charge of all the sweets and treats production. She is Mrs. Claus’s assistant and is in charge of the kitchen (let’s not dwell too much on the fact that the only female elf is both an assistant and works in the kitchen…or let’s do actually).

Wunorse Openslae (say it out loud): He’s responsible for Santa’s sleigh, as well as taking care of the reindeer.

We now of course, also have the relatively new tradition and commercial sensation of Elf on the Shelf®. The Elf on the Shelf concept was first conceived in 2005 by the Lumistella Company, according to the marketing material, to “create joyful family moments” through the magic of Christmas. The Lumistella Company website describes Elf on the Shelf® as a…

… fun-filled Christmas tradition that has captured the hearts of children everywhere who welcome home one of Santa’s Scout Elf® messengers each holiday season. These magical elves help Santa manage his nice list by taking note of a family’s Christmas adventures and reporting back to Santa at the North Pole nightly. Each morning, the Scout Elf helper returns to its family and perches in a new spot, waiting for someone to spot them. Children love to wake up and race around the house looking for their elf.

Many parents find joy in this tradition reflected in the magical belief of their children and/or the humorous (and sometimes quite naughty) escapades of their Elf on the Shelf. You can now buy elf outfits, elf pets and elf mates. Internet memes, videos and stories about Elf on the Shelf abound on the internet. It can take quite a bit of creativity and effort to maintain this tradition. In response, there are now pages and online shops that provide ideas and products for each day and there are even pages dedicated to Elf on the Shelf burnout!

This tradition does look fun but I’m happy to avoid it in my household, we have plenty of other, less stressful traditions to keep us busy.

Speaking of traditions, the ‘jolly little elf’ as Santa’s helper is not a common tradition in many mainland European countries. Instead, Santa is often accompanied by more sinister ‘helpers,’ who are often creepy and sometimes completely terrifying!

Santa’s Dark Helpers

Zwarte Piet

Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) originated in Holland and accompanies Saint Nicolas or Sinterklaas on St. Nicholas Day, 5 December, distributing sweets to well-behaved children or punishments to ill-mannered ones. Some historians believe that the origin of Sinterklaas and his helpers is linked to Odin’s Wild Hunt in which he was always accompanied by two black ravens, Huginn and Muninn. These ravens would listen at the chimneys, in a similar manner to Zwarte Piet, and tell Odin about the good and bad behaviours of the mortals in each home.

In medieval iconography, Saint Nicholas is sometimes associated with the taming of a chained demon, who was scorched with fire and forced to assist St. Nicholas. This demon was later re-imagined as a dark-skinned human during the early 19th century, in the likeness of Spanish Moors, who worked as Sinterklaas’ servant. The servant character of Zwarte Piet was first printed in the 1850 book Sint Nikolaas en zijn Knecht (Saint Nicholas and his Servant), by Amsterdam-based primary school teacher Jan Schenkman. This book also established another myth that is still part of St Nicholas Day intocht (arrival of St Nicholas and Zwarte Piet) traditions, which describes St. Nicholas and Zwarte Piet arriving in Holland from Spain by boat. Other stories about Zwarte Piet claim that he was a young Ethiopian slave rescued by St. Nicholas.

The image of Sinterklaas’ servant quickly evolved into a caricature of an African slave similar to the racist and distasteful American ‘blackface.’ This racially based custom continued into the 2000s. Although it could be argued that people painting themselves black as part of festive or religious rites is an ancient European custom, the servile characteristics, facial features and costumery of Zwarte Piet are unmistakably related to racist depictions of African slaves. This has been attested in several sources from the 1800s, which I will not repeat as they are deeply racist.

Since the early 2010s, there has been increasing controversy related to Zwarte Piet. Anti-racist groups trying to change or get rid of Zwarte Piet, have clashed with right-wing Nationalists, who want to maintain Zwarte Piet and have reacted with violence. In 2021, a popular alternative was suggested, that of Roetveegpiet or ‘Sooty Pete’ whose face is streaked with soot rather than painted black. However, a December 2020 survey by EenVandaag revealed that:

55 percent of those surveyed supported the traditional appearance of Zwarte Piet, 34 percent supported changing the character's appearance, and 11 percent were unsure. The survey reported that 78 percent did not see Zwarte Piet as a racist figure while 17 percent did. The most frequently mentioned reason of those who were in favor of changing the character was to put an end to the discussion.

Source: Eenvandaag 'Sinterklaas in coronatijd', via Wikipedia.

Krampus

While Zwarte Piet is morally problematic, Krampus is utterly terrifying! Krampus originated in the Central and Eastern Alpine regions of Europe. He is depicted as a large hairy man with black or brown fur, the cloven hooves and horns of a goat, a long pointed tongue and fangs or tusks. Krampus is widely recognised as a pre-Christian figure, originally called Percht, before he was transformed into the Devil as Christianity spread, renamed Krampus and made a subject of St. Nicholas’ will. In the Christian custom, Krampus accompanies St. Nicholas, whipping naughty children with a switch of birch. Those who are very naughty are stuffed into a bag or satchel on Krampus’ back and kidnapped, drowned, eaten or transported to Hell.

While St. Nicholas Day is celebrated in many parts of Europe on the 6th of December, Krampusnacht (Krampus Night) is celebrated on St. Nicholas Day Eve with large and raucous processions, called Krampuslaufen (previously known as Perchtenlaufen). People in costumes of animal furs and Krampus masks march through town streets accompanied by wild drumming and loud horns, to scare children into good behaviour. The festivities are traditionally lubricated by Krampus schnapps, a strong distilled fruit brandy. The video (2:05 mins) below features the 2022 Krampus run in Munich.

Krampuskartel or Krampus cards as a counterbalance to Christmas cards became popular in the late 1800s and have seen a resurgence in popularity in recent years. Krampus has even become a Hollywood horror icon, with a horror comedy film about Krampus released in 2015.

The video below features a scene from the Krampus (2015) movie with an eerie animated sequence describing how the character Omi first met Krampus as a child.

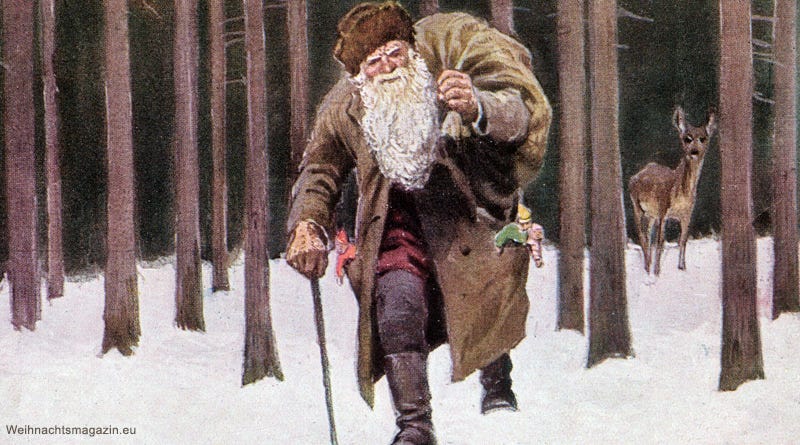

Less scary versions of Krampus evolved in different parts of Germany and other regions of Europe, where he is usually depicted as a sinister old man with a penchant for whipping naughty children.

Knecht Ruprecht

Knecht Ruprecht (Servant Rupert or Robert) is another dark helper for St Nicholas that originated in Germany. He is depicted as an old man wearing a black or brown robe with a pointed hood. He walks with a limp or holds a long staff, and a bag of ashes, and is occasionally depicted wearing little bells on his clothes. He sometimes rides on a white horse and he is sometimes accompanied by men dressed as old women, with blackened faces, or by fairies.

Knecht Ruprecht traditionally asked children if they could pray. Children who could recite their prayers were given apples, nuts and gingerbread, and if they could not, he hit them with his bag of ashes. In the Alpine regions of Germany, Knecht Ruprecht accompanies St. Nicholas and gives naughty children gifts of coal, sticks or stones, while St. Nicholas gives sweets to well-behaved children. Both St. Nicholas and Knecht Ruprecht are accompanied by the terrifying Krampus. Ruprecht is one of the German forms of the name Robert and was a common name for the Devil in Germany.

Belznickel

Belznickel, also known as Belschnickel, Belznickle, Belznickel, Pelznikel, Pelznickel, Bell Sniggle originated in the Palatinate region of Southwestern Germany and is often depicted as a misshapen and dishevelled old man dressed in ragged furs, sometimes wearing a mask with a long tongue. Similar to Knecht Ruprecht, Belznickel hunts misbehaving children and punishes them with a switch but he also gives out sweets, nuts and cakes to well-behaved children.

The Belznickel tradition accompanied German immigrants to America and is still practised among the Pennsylvanian Dutch. A 19th-century first-hand account of the "Beltznickle" tradition in Allegany County, Maryland states that Santa Claus was not known in his community and instead, children were visited by a different character:

He was known as Kriskinkle, Beltznickle and sometimes as the Christmas woman. Children then not only saw the mysterious person, but felt him or rather his stripes upon their backs with his switch. The annual visitor would make his appearance some hours after dark, thoroughly disguised, especially the face, which would sometimes be covered with a hideously ugly phiz - generally wore a female garb - hence the name Christmas woman - sometimes it would be a veritable woman but with masculine force and action. He or she would be equipped with an ample sack about the shoulders filled with cakes, nuts, and fruits, and a long hazel switch which was supposed to have some kind of a charm in it as well as a sting. One hand would scatter the goodies upon the floor, and then the scramble would begin by the delighted children, and the other hand would ply the switch upon the backs of the excited youngsters - who would not show a wince, but had it been parental discipline there would have been screams to reach a long distance.

Jacob Brown (1830) in a collection of Brown’s Miscellaneous Writings. Source: Wikipedia

The video (3:51 mins) below features a Pennsylvanian Dutch Belsnickel with a great explanation of the origins of the tradition.

Pere Fouettard

Pere Fouettard, which is French for ‘Father Whipper’ or ‘Old Man Whipper’ features in the Christmas customs of France, Belgium and Switzerland. He too is a sinister-looking man with scraggly unkempt hair and a long beard, armed with a whip or switch, sometimes carrying his spare switches in a wicker basket on his back. According to a folktale first told in the year 1252, he was a butcher or innkeeper who with his wife, kidnapped, robbed and killed wealthy children, then carved them up and hid them in salting barrels. St. Nicholas was said to have discovered the crime, brought the children back to life then forced Pere Fouttard into eternal bondage. Pere Fouettard now follows St. Nicholas, dispensing coal or beatings to naughty children.

St. Nicholas’ ‘dark helper’ characters can be found all across Europe, with similar characteristics and traditions albeit different names. Many regions in mainland Europe are experiencing a revival of these Christmas antagonists, often as antidotes to the commercialised and sanitised Christmas icon of Santa Claus or the Christian icon St. Nicholas and as part of a general revival of folk traditions.

While the tradition of the ‘dark helpers’ is fascinating, it’s not something I grew up with and I don’t feel pulled to incorporate into my own traditions. I’ll stick to the Anglo-American Christmas elves and Santa’s helpers for now but who knows, maybe when the children are older, there might be room for a bit of Krampus mischief.

I hope you’ve enjoyed exploring the fascinating history of Santa’s elves and his older and darker helpers. Next week’s article is all about the history of one of our most beloved Christmas icons, Santa Claus. In the meantime, enjoy exploring the episodes and articles from my Yuletide series, which are winter and Yule/Christmas-themed:

Share this post