I hope you all enjoyed a lovely winter solstice. Our household, including our ever-faithful house elf, Poppa, celebrated by waking up early to watch the solstice sunrise and ‘skol’ (cheers) the return of the sun.

Life was too busy to cook our usual winter solstice feast but I did manage to cook the delicious fig and ginger pudding with butterscotch brandy sauce for dessert. We all joined in for our traditional ‘stir up’, each of us stirred the pudding batter and made a wish for the family, before I popped a trinket into the batter for good luck. The trinket was found on the first mouthful, which in itself was lucky, it could have taken days to find as we slowly made our way through the leftovers.

Food and food traditions are an integral part of any festivity, heavily seasoned with folklore and folk customs unique to their particular region, or even particular families. This week we are diving into the delicious world of Christmas and Yule feasts, including the main course, desserts, sweats, treats and warm beverages. Get inspired to create your own feast for the approaching mid-winter celebration of Yule. Enjoy!

Dinner: The Main Meal

Many European cultures that celebrate Christmas enjoy their main festive meal on Christmas Eve with family and/or close friends. However, in places like Australia, Christmas Day lunch is often the main meal and we will explore the joys of an Aussie Christmas later on in the year.

Winter solstice feasting is an old tradition, as we explored in previous articles, Echoes of the Ice Age: Winter Solstice and Mother’s Night and The Origins of Christmas, the 12 Days of Christmas and Twelfth Night. These traditions were absorbed into Christian celebrations of Christmas and by the Middle Ages, Christmas was a twelve-day extravaganza of feasting and revelry. It started on the morning of December 25, after the month-long fast of Advent, and culminated on January 5 with Twelfth Night. During this time, wealthy lords were expected to give their serfs twelve days off from labour and provide them with a festive meal. Royalty and the wealthy upper class gorged themselves for twelve days with elaborate meals, rich food and plenty of alcoholic drinks. The servants and serfs had to make do with pies, offal and ale.

Niall Edworthy stated, in his book The Curious World of Christmas (2008) that:

During the Middle Ages, the tables of the rich were filled with “sumptuous displays of foods throughout the twelve days of Christmas. Goose was a common dish and the bird was often given a shiny, golden appearance by basting it in a mixture of butter and the highly coveted and expensive spice saffron. Pork or wild boar often formed the pièce de resistance of the Christmas feast, and the roasts were carried into the dining halls amid great fanfare with lemons stuffed into the beasts mouths”… In contrast, the medieval rich gave the poor a Christmas treat of deer innards, called ‘umbles,’ which were made into pies… the origin of the term ‘humble pie’ (p. 19).

After the Puritan-led bans on Christmas celebrations, the Victorian revival of Christmas allowed the growing middle class to indulge in more truncated versions of the Medieval and upper-class Christmas excesses by incorporating more commonly available and affordable meats and other foods to grace their festive tables.

The main course for many festive Christmas and Yule meals across Europe features roasted meats of some description, particularly roast boar/pig, duck, goose, turkey, and the ubiquitous roast beef. These were often accompanied by roasted vegetables and other side dishes and trimmings specific to each region. The most symbolic and much-anticipated part of the Christmas or Yule feast remains the roast meat, which is still presented with fanfare, even if the old processions and rituals are considered passé.

Roast Boar/Pig

Roast boar or pig was often the centrepiece of the Christmas meal. Boars were endemic in the UK until the 13th Century when they became extinct due to hunting. According to the UK’s Wildwood Trust:

A revival was attempted in the 1700’s but these didn’t re-establish due to further persecution. In the 20th century, wild boar were introduced as a livestock animal, farmed for their meat. However following escapes from both these farms and other captive populations, populations of wild boar seemed to re-establish themselves in the 1980s-1990s.

Boars are dangerous to hunt and thus a much sought-after quarry. They are difficult to kill due to their solid body build, thick skin, and large head protected by an extremely strong skull. Boars can run fast, move quickly, and are good swimmers. They are also aggressive and strong animals with sharp tusks that protrude from their mouths. Stories of Kings and important legendary figures who are killed, maimed or injured by boars are common in European history and folklore.

An old Yule custom of the Germanic and Nordic people involved the public display and ritual of bringing in a boar’s head to the Yule feast held in the Great Hall. The short documentary (7:17 mins) below, from the History Channel’s Secrets of the Vikings, gives some insight into what Nordic feasting would have looked like.

The boar was considered a sacrifice to Freya the Nordic goddess of love, magic, sex, battle and death, and her brother Freyr, god of kingship, fertility, peace, prosperity, fair weather, and good harvest. In Norse mythology, Freya was often depicted riding a giant boar called Hildisvíni, into battle.

Freyr, on the other hand, was given a magical boar as a gift by the dwarf Brokkr, who also made Thor’s famous hammer, Mjölnir. This boar was called Gullinbursti, which meant Gold Mane or Golden Bristles, on account of its bristles being fashioned from gold, which were so bright that they lit up the sky as if it were day, even in the middle of the night. Freyr is sometimes described as riding across the heavens on the back of Gullinbursti, an obvious correlation with the rebirth of the sun at the winter solstice.

Then Brokkr brought forward his gifts: … to Freyr he gave the boar, saying that it could run through air and water better than any horse, and it could never become so dark with night or gloom of the Murky Regions that there should not be sufficient light where he went, such was the glow from its mane and bristles. Snorri Sturluson. Prose Edda. c 1220.

The Celts also considered the boar to be a sacred and mythical creature. One prominent figure in Celtic mythology linked to the boar is King Arthur, who in several stories, pursues the enchanted boar Twrch Trwyth, said to be a cursed king, sometimes with the help of his men and his hound. Another tale from the King Arthur cycles featuring rich descriptions of the great hunt for Twrch Trwyth is the Welsh romance prose Culhwch and Olwen. The short 2:25 minute film by Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority tells the story of brave warrior Culhwch’s quest for his beautiful bride Olwen on the wild and rugged Preseli Hills.

The tradition of the boar’s head is also connected to pre-industrial agricultural cycles, where pigs were traditionally slaughtered and their meat preserved through the months of November and December, in time for the Christmas feasting.

At this point in the year pigs were consuming the last of the forest’s free pig feed: acorns and beechnuts. Small farmers either had to find more feed, let the pigs go hungry, or slaughter them. Source: The Free Dictionary

Regardless of the origin, the tradition of bringing in the hog spread throughout Western Europe and became a common feature of Christmas celebrations for the wealthy ‘upper class’ and royalty.

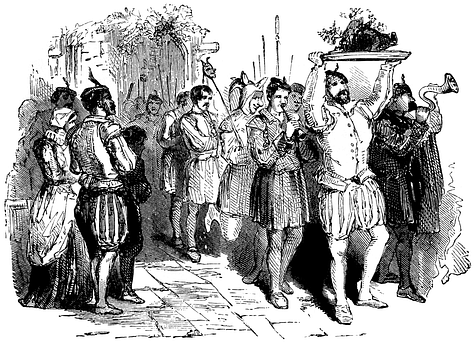

Medieval Christmas festivities were celebrated with elaborate feasts, performances and games, throughout the season. One such Yuletide tradition was the Roasted Boar’s Head Feast, those with the means would have a boar’s head pickled, stuffed with forcemeat, roasted and then gilded with gold leaf, served on a platter with a fruit (orange/apple) in it’s mouth surrounded by herbs, delivered with a performance of musicians and entertainers creating a grand ceremony as it was presented to the head of the household. King Richard III Visitor Centre. Medieval Christmas: The Boars Head Festival

Although the Puritan Christmas bans were lifted in the 1700s, the boar’s head tradition disappeared for the most part, replaced by quieter customs and more affordable or available meats. However, the Boar’s Head Feast is still celebrated at Christmas by some old English and American institutions, such as Oxford University’s Queen’s College, where the tradition is known as the Boar’s Heady Gaudy. The decorated boar’s head is displayed on a platter and paraded around the dining room, accompanied by a procession headed by a solo singer and followed by the college choir signing the Boar’s Head Carol.

The video below (2:04 mins) features the Randolph Singers, singing the Boar’s Head Carol with the lyrics and a translation of the Latin chorus at the end.

The Christmas Bird (Turkey, Duck, and Goose)

Roast goose and duck also have a long history as a traditional dish for Christmas and Yule. They were used to grace the festive tables of rich and poor throughout Europe. Duck is still the most popular Christmas meat for the Danes, while goose is still popular in France and England, although these days, many European countries, like their North American cousins, enjoy turkey at Christmas.

In the Middle Ages, particularly during the reign of Henry VIII, royalty and the wealthy upper classes liked to display their wealth at Christmas by serving rare and exotic birds for Christmas feasts, such as swan, peacock, and the newly introduced turkey. Goose and duck were also served. Poultry, particularly duck and goose, were a popular choice for the Christmas feasts of the less wealthy as these birds were readily available and relatively affordable during the winter months.

Turkey

Turkeys are native to North America. They were first brought to Europe in the 1500s by the Spanish, from flocks of turkeys that had been domesticated for thousands of years by Aztecs in Mexico. Before establishing their own flocks on English soil, the English bought their turkeys from Turkish traders, thus their commonly accepted English names, while the French call turkey dinde, short for poulet d’inde (chicken of India), as Columbus initially thought he had landed in India when he first arrived in the Americas. English landowner and trader, William Strickland, imported the first flocks of turkeys for farming in 1526, for which he was granted a coat of arms, which included a depiction of a “turkey cock in his pride proper”.

Turkeys soon became synonymous with Christmas as they became more commonly available in England. By the Victorian era, the growing middle class preferred to purchase turkeys for their Christmas meal, while duck and goose were preferred by the poorer working class.

‘A Christmas dinner, with the middle classes of this Empire, would scarcely be a Christmas dinner without its turkey, and we can hardly imagine and object of greater envy than is presented by a respected portly pater familias carving, at the season devoted to good cheer and genial charity, his own fat turkey and carving it well’. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, Isabella Beeton (1861).

Turkey drives became a common site in the regions around London, particularly in Norfolk and Suffolk. From as early as August, farmers would walk with flocks of up to 1,000 turkeys towards the London markets. This often took up to three months as apparently, turkeys tend to stroll and farmers needed to ensure the birds didn’t lose too much weight on their journey. The long walk to London was hard on the turkey’s feet so farmers protected them by making little leather boots, wrapping the turkey’s feet in rags or coating their feet in tar. After they reached London, they were fattened again for a short time before being dispatched in time for the Christmas markets.

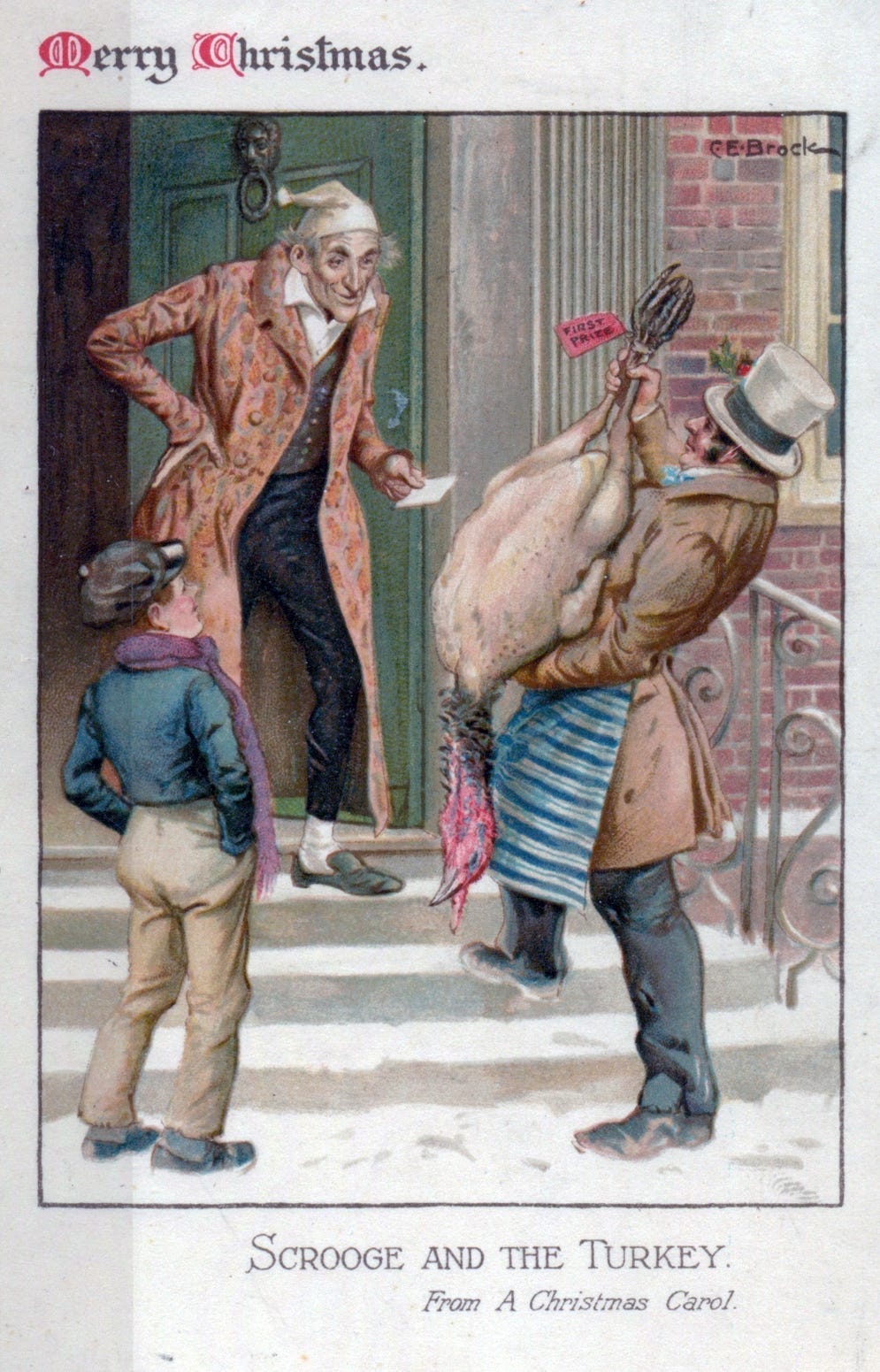

Charles Dickens helped to popularise the Christmas turkey in his novella A Christmas Carol, when a transformed Ebenezer Scrooge buys a Christmas turkey for the poor Cratchit family.

“An intelligent boy!” said Scrooge. “A remarkable boy! Do you know whether they’ve sold the prize Turkey that was hanging up there? — Not the little prize Turkey: the big one?”…. “I’ll send it to Bob Cratchit’s!” whispered Scrooge, rubbing his hands, and splitting with a laugh. “He sha’n’t know who sends it. It’s twice the size of Tiny Tim.” A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens (1843).

Goose

During the Middle Ages, goose was a popular choice for festive meals due to its availability, and rich flavour. They were an affordable indulgence for the Victorian-era working class and even the poor. In some parts of Europe, the tradition of goose clubs or Christmas goose clubs evolved, particularly in England and Scotland during the 18th and 19th centuries. The purpose of the goose club was to pool resources and ensure that each member of the club could enjoy a festive meal centred around a roast goose for Christmas. Participants would contribute a small sum of money into a collective fund on a weekly or monthly basis throughout the year. The accumulated funds would then be used to purchase geese for each club member.

The geese were commonly bought in bulk from local farmers or markets. Typically, a designated goose club day was determined, often a few days before Christmas, when the geese would be distributed to the club members.

When the big day finally arrived, everyone who had paid in would congregate at the pub to claim their Christmas goose. To make it fair, all the names would be put into a hat. One goose would be held up and a name would be drawn. And, be it fat or scrawny, if your name was drawn, that’s the goose you got. At home the goose would be cleaned, prepared, and probably filled with sage and onion stuffing. Since most houses didn’t have ovens, all those geese would be taken to the bakers for roasting. Then on Christmas morning, everyone went to collect their dinner from the bakery. CuriousRambler.com

The distribution of geese from the goose club was often accompanied by celebrations, feasting, and merriment. These clubs provided an opportunity for people to come together, and strengthen community bonds during the holiday season, before the more private and family-centred Christmas Day celebration.

The tradition of goose clubs gradually declined with the changing socio-economic landscape and the shift towards more individualised celebrations. Turkey became a status symbol for the Victorian middle classes, where they were considered a luxury reserved for the Christmas season. However, after the 1950s, turkey became much more affordable due to improved farming methods, and their large size meant that families were able to host large gatherings. The Christmas goose thus gave way to the more popular turkey in modern times.

Nordic Smörgåsbord

Other regions in Europe have similar but varied Christmas meals. Christmas Eve dinner in Scandinavian countries features the traditional Nordic smörgåsbord, a buffet of food that often includes glazed hams with mustard, potatoes (roasted and/or mashed), salads, pork or lamb ribs, gravlax and a whole baked salmon.

Italian Christmas Dinner

Fish also features heavily in the Italian Christmas Eve dinner, which is known as La Vigilia di Natale (The Vigil of Christ’s Birth) or the Feast of the Seven Fishes. It was traditionally the final fasting day before the Christmas Day feast, celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ. These days, fasting may not be integral to the Christmas Eve feast but it still centres heavily around seafood.

Italy’s main Christmas feast happens on Christmas Day and involves several courses, typically starting with:

An Antipasti course of cold and hot appetizers, followed by a first course (usually pasta or meat-based). The grand affair of the main second course then commences (usually an extravagant meat or fish dish), accompanied by tasty side dishes of fried artichokes, cauliflower, fennel gratin and roasted potatoes.

French Christmas Dinner

The French also enjoy multi-course meals, with their main feast on Christmas Eve, called Le Réveillon, from the French word réveil which means ‘awakening’, describing the custom of staying up all night for the arrival of Père Noël, the French Santa Claus. The first course is the Apéro (short for apéritif), which are small bites of food designed to whet the appetite before the main course, like smoked salmon blinis, prunes wrapped in bacon, gougères (baked cheese puffs), rillettes of all kinds (pork, salmon or sardines) and canapés, consisting of small slices of bread or puff pastry topped with some savoury food (charcuteries, cheeses, etc). This course is generally served in the lounge room with bubbles (champagne or cider), before moving to the dining room for the rest of the dinner.

The second course or starter usually includes foie gras on toasted baguette slices. There might also be escargots en beurre (snails cooked in butter), pâté en croûte (pâté encased in bread) and chestnut soup. Seafood dishes are popular, especially in the French coastal regions. The third or main course involves some kind of poultry, like a large roasted dinde (turkey) with chestnut stuffing, served with roasted potatoes. For smaller gatherings or in the Alsace and Dordogne regions roast goose or duck is served. Some French families prefer braised rabbit with prunes. The fourth course before the dessert includes cheese boards and salads.

French Canadians traditionally enjoy tourtière for their Christmas Eve feast. Originating in Quebec during the 1600s, the tourtière is a double-crusted meat pie made from a blend of meats — often minced beef, veal and pork, with small cubes of potatoes and spices. The tourtière filling, and ‘proper’ recipe varies according to region.

Christmas/Yule Sweets and Treats

Once the Christmas meal is eaten, sweet and rich desserts are served to finish the festive feast.

Plum Pudding

Plum pudding, also known as Christmas pudding, is a traditional dessert in English Christmas celebrations. It has a long history dating back to the Middle Ages, where it started as a sweet and savoury dish called plum pottage or frumenty, which was more like porridge made with beef and mutton, suet, milled wheat or oats, and various fruits and spices. Frumenty was placed in a bag (originally animal gut or stomach) and boiled to make plum pudding. As dried fruit and sugar became more available and cheaper in the 16th and 17th Centuries, the savoury elements of plum pudding began to decrease and the dish became sweeter until the meat was removed altogether in the 18th Century. The modern plum pudding recipe first appeared in the Victorian era.

Modern plum pudding typically consists of a mixture of suet (a type of fat), breadcrumbs, flour, sugar, spices such as cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves, and dried fruits such as raisins, currants, and sultanas. Plum pudding originally included plums but as they were so popular during the Victorian era, they became difficult to come by and so other dried fruits were substituted. Plum puddings also include candied citrus peel, and sometimes grated carrot or apple. The mixture is often flavoured with brandy, rum, or other spirits and is traditionally steamed for several hours, which gives it a dense and moist texture. Steaming also allows the flavours to meld together and develop a deep, rich taste.

The sugar and alcohol content of plum puddings, as well as their method of cooking, means that they can be stored for a long time and are amenable to canning. Canned or tinned puddings were a popular addition to Christmas parcels sent to soldiers on the frontlines from WWI onwards.

Plum pudding is typically made well in advance of Christmas, sometimes even months ahead. This allows the flavours to develop and mature over time. Many families have their own cherished recipes that are handed down through generations.

Stirring the pudding is an important and symbolic tradition associated with plum or Christmas pudding. It is typically done on a specific day known to Christians as “Stir-up Sunday,” which falls on the last Sunday before Advent, usually five weeks before Christmas. The tradition involves gathering family members together to take turns stirring the pudding mixture with a wooden spoon. As they stir, they make a wish or say a prayer for the upcoming year. It is believed that everyone in the family should have a chance to stir the pudding to ensure good luck and prosperity.

Another pudding tradition involves adding silver coins, charms or a blanched almond to the mixture before stirring, with the belief that finding them in the pudding would bring good fortune to the person who discovered them.

Sing, sing, what shall I sing?

The cat’s run away with the pudding string.

Do, do, what shall I do?

The cat has bitten it quite in two.Old English Nursery Rhyme

Mince Pies

The origins of mince pie are similar to the origins of plum pudding, but instead of the sweet and savoury frumenty being turned into steamed pudding, the frumenty was placed into pies and baked. These pies were initially called Christmas pies or mutton pies. Over time and similarly to plum pudding, the recipe for mince pies evolved, and the meat content decreased while the sweetness and fruitiness increased. By the 18th Century, the meat was eliminated altogether, and the filling primarily consisted of a mixture of dried fruits, such as raisins and currants, and candied citrus peel, mixed with suet, sugar, spices, and sometimes brandy or rum.

Today, mince pies continue to be a staple of Christmas celebrations, enjoyed as a traditional dessert or sweet snack during the festive season.

Christmas Cake

Christmas cake is another English Christmas tradition with the same origins as Christmas pudding and mince pies. However, Christmas cake was reserved for the wealthy upper classes because they had ovens in their kitchens with which to bake their cakes, rather than needing to boil pudding on a stovetop or over fire. Christmas cake became popular during the Puritan Christmas bans as they were allowed, while plum pudding and mince pies were banned as displays of excess, a rather hypocritical stance. Christmas cake remained a firm favourite of the rich upper class during the Victorian era and eventually became a popular seasonal treat for the working class as ingredients became cheaper and more accessible, and as more people were able to install ovens in their kitchens.

Christmas cakes are also made in advance. They are usually kept upside down in an airtight container and ‘fed’ a small amount of brandy, sherry, or whisky every week until Christmas when they are traditionally decorated with a covering of white marzipan and topped with holly. The Scottish Christmas cake, also known as the Whisky Dundee, is a popular variation of the Christmas cake. It is a light crumbly cake with currants, raisins, cherries and Scotch whiskey, decorated with blanched almonds.

King Cake

Another popular and more widespread sweet treat associated with Christmas is the King Cake. This traditional confection is particularly popular in Germany, France, Spain, and Portugal, and various regions influenced by these cultures. It was known in England as Twelfth Night Cake due to its connections with festivities surrounding the Christian celebration of Epiphany, also known as Three Kings’ Day or Twelfth Night, which commemorates the visit of the Magi to the baby Jesus. However, in England, the Twelfth Night cake became less popular and was eventually displaced by the Christmas cake during the Victorian Era.

The King Cake is different to other Christmas cakes because of the surprise hidden inside. Traditionally, a small trinket, figurine, or dried bean known as a fève (French for bean) is baked into the cake, representing the baby Jesus. The three spices used in the recipe represent the Magi. Whoever discovers the trinket or bean in their slice is crowned the ‘king’ or ‘queen’ of the festivities and given a golden paper crown to wear. This person is then responsible for hosting the next gathering or providing the King Cake for the following year. Figurines of pop culture icons can be used instead of the fève in secular versions of the cake.

The King Cake is typically a ring-shaped cake made from rich, yeasted dough that is often flavoured with hints of cinnamon or nutmeg. It may be adorned with vibrant coloured sugar or icing in shades of green, gold, and purple, symbolizing faith, power, and justice, respectively, the gifts given to Jesus by the three Magi.

In southern France, the cake is called gâteau des rois (‘kings’ cake’). In Germany and Switzerland, the cakes are called Dreikönigskuchen (‘three kings cake’), and are shaped like wreaths with an almond instead of the fève. In Portugal, the cake is called Bolo-rei (‘king cake’) and in Spain, Latin America and Spanish-speaking areas of the United States the cake is called Roscón de Reyes (‘cake of kings’). In northern France, Quebec, Luxembourg and Belgium the cake is instead made of puff pastry, filled with frangipane and is called galette des rois, in Flemish Dutch it is called koningentaart (both translate to ‘kings’ tart’). In Italy and Italian-speaking regions around the world, the tradition of Christmas panettone (‘little loaf bread’), has roots dating back to the Roman Empire.

Gingerbread and Spice Cookies

Other favoured sweet treats for the festive season are gingerbread and spice cookies.

The Origins of Gingerbread

Gingerbread has a fascinating history that stretches back to the ancient civilizations of Asia, where ginger was highly valued for its medicinal properties. Ginger and other spices spread to Europe from China, Southeast Asia, and India through the Middle East, with Muslim traders along well-established trade routes such as the Silk Road. The first known recipe for gingerbread dates back to 2,400 BC in Greece, where it was made by combining breadcrumbs and honey with ginger and other spices. These early gingerbread treats were often shaped into intricate designs, such as animals, flowers, and religious symbols.

Some sources attribute the origins of gingerbread in Europe to 992 AD, when an Armenian monk named Gregory of Nicopolis, shared his gingerbread-making knowledge with Christian bakers in France.

During the Crusades, Europeans returning from the Middle East also brought back spices like ginger, cinnamon, and cloves. Ginger became a favoured delicacy among the nobility and clergy, often presented as gifts and served at lavish feasts. Gingerbread was not only enjoyed for its delicious taste but also appreciated for its supposed medicinal properties, including aiding digestion and soothing various ailments.

The tradition of gingerbread making and its association with Christmas became widespread in Europe during the Middle Ages. In medieval Europe, gingerbread was not only considered a delicious treat but it was also formed into works of art. Elaborate gingerbread creations, including figures of animals, people, and even entire scenes, were crafted by skilled bakers and artisans. These intricately decorated gingerbread creations were often showcased at festive occasions, including Christmas markets and fairs, where the term fairings originated, referring to gingerbread that was sold to marketgoers from special gingerbread stalls. Gingerbread works of art also flourished during the Renaissance period in Europe.

And I had but one penny in the world, thou should’st have it to buy gingerbread.

William Shakespeare, “Love’s Labor’s Lost”

Gingerbread Men

Queen Elizabeth I is credited with the creation of the first gingerbread men, which she had made to resemble the dignitaries that visited her court, and to whom she gifted the gingerbread men.

In 1875, the American children’s magazine, St. Nicholas published a fairy tale about The Gingerbread Man (also known as The Gingerbread Boy):

In the 1875 St. Nicholas tale, a childless old woman bakes a gingerbread man, who leaps from her oven and runs away. The woman and her husband give chase, but are unable to catch him. The gingerbread man then outruns several farm workers, farm men, and farm animals.

I’ve run away from a little old woman, A little old man, And I can run away from you, I can!

The tale ends with a fox catching and eating the gingerbread man who cries as he is devoured, “I’m quarter gone…I’m half gone…I’m three-quarters gone…I’m all gone!” Wikipedia

In different versions and retellings, the line about being eaten is sometimes excluded and in others, the Gingerbread Man famously taunts his pursuers with the line:

Run, run as fast as you can!

You can’t catch me.

I’m the Gingerbread Man!

Regional Gingerbread Traditions

As gingerbread spread throughout Europe, different regions developed their own variations and traditions. In England, gingerbread initially referred to preserved ginger, which was often shaped in intricate moulds and decorated with gold leaf. Over time, gingerbread evolved into a baked sweet treat, more akin to a biscuit or cookie that was often enjoyed during festive occasions and celebrations at Christmas time. These gingerbread biscuit styles are often stamped or pressed into intricately carved wooden moulds, or shaped with cookie cutters and decorated with piped icing.

In Germany, gingerbread, known as Lebkuchen, is a cherished Christmas tradition. The city of Nuremberg in Germany is particularly renowned for its delicious and intricately decorated Nuremberg Lebkuchen. These gingerbread treats were often made with a combination of spices, honey, nuts, and citrus peel, resulting in a distinctive flavour. Gingerbread cookies and Lebkuchen hearts, adorned with heartfelt messages, are popular as gifts and tokens of affection during the festive season.

In France, there are many regional variations of the pain d’épices (spice bread) but the ones from Dijon in Burgundy are the most famous, although before the end of the 19th Century, Reims was first regarded as the ‘French capital of gingerbread.’ Interestingly, the regional French pain d’épices does not contain ginger and the pain d’épices of Dijon only contains aniseed and is made with jam and fruits. Spices were popular in the French Middle Ages but these spices declined in popularity and more recently, pain d’épices have become sweeter to cater for the changing French palette and tourists.

The Scandinavian countries of Norway, Denmark and Sweden, bake a popular thin, crisp spiced biscuit called pepparkakor (pepper biscuits) as they used to contain a lot of pepper. These days most modern recipes omit the pepper but retain the other spices of cloves, cardamom, cinnamon and ginger. They are cut with cookie cutters, decorated with piped white icing, given as gifts, and are often strung and hung as Christmas decorations.

The Netherlands have their own version of spice biscuits called speculaas that are popular during the Christmas season, especially on December 5 or 6 to celebrate St. Nicholas’ Day, when well-behaved children are rewarded with speculaas biscuits in their shoes. Speculaas are made with a special mix of spices that includes ginger, cinnamon, cloves, mace, pepper, cardamom, coriander, anise seeds and nutmeg. Many of these spices weren’t commonly available until the 17th century when the Dutch East India Company opened up a direct trade route between the Netherlands and Southeast Asia. Speculaas are also called Dutch Windmill Cookies, as many of them are made using a traditional biscuit mould in the shape of a windmill.

In Poland, gingerbread cookies are called pierniczki, and the Polish city of Toruń has been famous for its pierniczki cookies since the Middle Ages. In the Czech Republic, these cookies are called pernik, with the Czech cities of Pardubice and Prague famous for their gingerbreads. The Russians call their gingerbread cookies pryaniki, and the old Russian cities of Tula, Volgograd and Arkhangelsk are still famous for their gingerbread.

The Croatian licitar is slightly different. The gingerbread is made into symbolic shapes such as dolls, birds, horseshoes and wreaths, then dipped into a shiny red glaze and decorated with intricately piped royal icing.

Licitars adorn Croatian Christmas trees and are given away as a token of love to family members and lovers, who keep them forever and display them in their homes. The Spruce Eats

Gingerbread Cake

While gingerbread is often baked as a biscuit, it can also be baked as a dark and spicy cake like the Polish piernik or some versions of the French pain d’épices. I love using my Gramma Doris’ recipe for gingerbread. Gramma was a station cook on outback stations in North Queensland before joining as a cook for the Australian Army during WWII. I suspect that her recipe for gingerbread was learned or adapted and used from her time in the army, as the recipe replaces egg with bicarb soda to account for wartime egg shortages. The ingredients and portions are also easy to remember and the recipe is easy to make. Gramma’s recipe forms the basis of the traditional Yule Log Cake I bake for our annual Yule celebration at midwinter, which we will explore further in this article. I also use this recipe for my children’s kagemand (Danish ‘Cake Man’) birthday cakes.

Gingerbread Houses

The tradition of gingerbread houses began in medieval Europe as part of the decorative centrepieces created for festive occasions by royalty and the wealthy upper class. During the 16th Century, the fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel became popular in Germany and it was first published in Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Grimm’s Fairy Tales) by the Brothers Grimm in 1810. Although the story is not particularly ‘Christmassy,’ the concept of the witch’s gingerbread house, decorated with sweets was quickly translated into real gingerbread houses that became popular at Christmas.

The tradition of making gingerbread houses soon spread to other European countries and eventually made its way to America through German immigrants. Today, gingerbread houses are a beloved part of Christmas celebrations in many places around the world. Families, friends, and communities gather to build and decorate gingerbread houses as a festive activity, often using royal icing, gumdrops, lollies, and other confectionery delights.

Yule Log Cake

The Yule Log Cake, also known as Bûche de Noël in French, is another traditional dessert with deep roots in European winter solstice and Christmas celebrations. The Yule Log Cake represents the ancient custom of burning a large log, known as the Yule log, during the winter solstice. We’ll explore the Yule log tradition in a future article.

Over time, the Yule Log Cake emerged as a culinary adaptation of the Yule Log tradition. It is a festive dessert shaped like a log, typically made of sponge cake or rolled cake filled with cream, ganache, or buttercream. The exterior of the cake is often covered with chocolate frosting, shaped into a bark-like texture, and it is decorated with marzipan or meringue mushrooms, powdered sugar to resemble snow and other edible ornaments.

The Yule Log Cake is not only a delicious treat but also serves as a decorative centrepiece for festive celebrations. In some traditions, a small piece of the Yule Log Cake is saved until the following year to be thrown onto the Yule fire, bringing good luck.

Making the Yule Log Cake is one of my favourite annual traditions for our midwinter Yuletide party, celebrated on or around the 15th of July (southern hemisphere). As mentioned in the previous section, I use my Gramma Doris’ gingerbread recipe, baked in flat tins. Cream cheese sweetened with icing sugar is spread on top of the gingerbread, followed by strawberry or rasperry jam, and then the whole thing is rolled, wrapped tightly in cling wrap and placed in the fridge. While the log is chilling, I make marzipan mushrooms, using red food colouring for the toadstool caps and I whip up chocolate buttercream frosting.

The log is then taken out of the fridge, unwrapped, placed on its serving block and covered with the chocolate frosting to look as much like bark as possible, helped by crumbling a ‘Flake’ chocolate over the top. The marzipan mushrooms are placed on and around the log along with bits of greenery for decoration; ivy, pine branchlets, mint, wild fennel, even mallow, anything that is at hand and takes my fancy. In a final flourish, my gorgeous Yule gnome is placed on top. He lives in a special box for most of the year and only comes out to carry out his Yule duties before being packed away again. Maybe I should get him a friend, or a wife so he doesn’t get lonely!

Other Sweet Treats

Other sweet treats are also important delicacies for festive season traditions, including oranges, chestnuts and porridge.

Oranges

Oranges have long been associated with Christmas. Dried orange slices and orange pomanders are frequently used as festive decorations, while fresh oranges can be found in warm spiced wine recipes and festive dishes.

Pomander balls have an interesting history. In medieval Europe, pomanders were cloth bags or perforated boxes of fragrant, dried herbs, used by herbalists to ward off illness, protect against malintent or bring good fortune. Sometimes the strongly scented ambergris (dried secretion from the sperm whale’s bile duct) was added, and this led to the name for pomander, derived from the French pomme d’ambre, meaning ‘apple of amber.’ These days, pomanders are made of fresh oranges pierced by cloves and are still used for their fragrance and as decoration, if no longer as medicine.

Oranges are not native to Europe but were introduced to the region in a similar way to spices, through Muslim traders, though they remained wildly expensive and out of reach for most Europeans. Oranges and spices were popularised by the Crusaders in the 11th and 12th centuries during their travels to the Middle East and Mediterranean regions.

The Crusaders were captivated by the exotic flavours and scents of these fruits and brought back samples and seeds with them upon their return to Europe. Oranges were initially cultivated in southern European countries such as Spain, Portugal, and Italy, where the Mediterranean climate was favourable for their growth. Harvest time for oranges in the Mediterranean coincided with Christmas and oranges became a prized and cherished fruit of the festive season, particularly amongst the wealthy, clergy and royalty who could afford them.

Over time, the cultivation of oranges expanded throughout Europe, with the introduction of new varieties, improved agricultural techniques and the development of orangeries. The concept of orangeries can be traced back to the Renaissance period in Italy, where wealthy patrons and aristocrats sought to cultivate exotic plants, including citrus fruits, as a symbol of status and luxury.

Orangeries were large and elaborate greenhouses, constructed as extensions of grand estates, palaces, and botanical gardens. They became popular amongst the wealthy upper class in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries and were built primarily to provide a controlled environment for citrus trees during the winter months, allowing them to thrive and bear fruit even in colder climates. They were also used to grow other exotic, heat-loving plants and became a popular setting for elegant tea parties, afternoon receptions, and musical performances.

Today, with modern transportation and advancements in agriculture, oranges are available year-round in many parts of Europe. However, the association of oranges with Christmas traditions and the nostalgia for their historical significance continue to make them a popular symbol of the season.

Chestnuts

Chestnuts have been cultivated and consumed as a staple from Europe to North America and Asia for thousands of years, especially in mountainous regions where grains are difficult to grow. In Europe, chestnuts were widely available and played an important role in the diet of rural communities. Roasting chestnuts over an open fire or buying roasted chestnuts from street vendors became a popular tradition during the autumn and winter seasons when they were available.

Chestnuts were frequently included as a key ingredient in traditional Christmas recipes, such as stuffing for poultry, soups, and desserts. When the crusaders returned to Europe with sugar, countries like Italy, France, and Spain, began producing chestnut-based sweets and pastries, such as marrons glacés (candied chestnuts) and chestnut mont blanc, which became cherished Christmas delicacies.

North America had its own species of chestnuts, which was also a staple food for the First Nations peoples across Eastern America. However, the American chestnut species was almost wiped out entirely in a matter of years by the chestnut blight, which was accidentally introduced into America at the end of the 1800s on imported Japanese chestnut trees. This 9-minute documentary provides an excellent summary of the history and status of the chestnut tree in America.

Porridge

The tradition of eating porridge during Christmas has deep historical roots and is observed in various cultures around the world. Porridge, a simple dish made by boiling grains or legumes in water or milk, has been a staple food for centuries. Western European countries most often eat porridge cooked with oats, while in Eastern Europe porridge made with a corn or wheat base is popular and in Northern Europe, porridge with a rice base is most popular.

We have already learned about the English porridge called plum pottage or frumenty, which contained beef and mutton, suet, milled wheat or oats, and various fruits and spices. Frumenty evolved from the simpler, plainer porridge that early Christians traditionally ate on Christmas Eve after fasting throughout the month of Advent, in preparation for the twelve days of Christmas feasting.

In the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, a specific type of Christmas porridge called Risengrød or Risgrynsgrøt holds a special place in holiday celebrations. It is a rice porridge made by simmering rice in milk, sweetened with sugar and a touch of cinnamon and topped with a pat of butter. The tradition of eating risengrød during Christmas is believed to have originated from ancient fertility rituals where offering porridge to the spirits of the land was a way to ensure a good harvest in the coming year. Today, it is a popular dish served on Christmas Eve, often with a hidden almond in the porridge. The person who finds the almond is said to have good luck in the coming year. The Yule tradition of leaving out some pudding and butter for the Yule tomte/nisse will be explored in an upcoming article.

This short and sweet video (1:20 mins) features the Norwegian Nisse and the tradition of leaving him rice porridge with butter for Yule.

Porridge is also important in the Christmas traditions of Finland, where a version called Joulupuuro is prepared. Joulupuuro is a rice porridge similar to risengrød and is typically served on Christmas morning. It is also customary to hide one whole almond in the pot, with the person finding it receiving a small gift or good luck.

In some Eastern European countries like Poland and Ukraine, a wheat-based porridge known as Kutia or Kutya is prepared for Christmas Eve, or on January 6, which is the date of Christmas according to the Russian Orthodox Church. Kutia is made with cooked wheat berries mixed with honey, dried fruits, nuts, and sometimes poppy seeds.

Laufabrauð

Laufabrauð or leaf bread, sometimes also called snowflake bread, is a popular treat in Iceland during the Yule/Christmas season. It is a round, very thin flatbread, decorated with leaf or snowflake-like geometric patterns and fried in hot fat or oil. The patterns are either cut by hand or with a heavy brass roller, called laufabrauðsjárn (leaf bread iron). The whole family is often involved in making laufabrauð and it is traditionally served on Christmas day with savoury dishes but can also be dusted with icing sugar and served as a sweet treat.

Festive Drinks

We can’t discuss festive feasts and sweets without also exploring the warm alcoholic beverages that also symbolise the festive season.

Glögg, Glühwein, and Mulled Wine

Glögg is a traditional Scandinavian warm spiced wine beverage typically enjoyed during the winter months, especially around the holiday season. It is similar to the English mulled wine or the German glühwein and is made by simmering red wine with a blend of spices like cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, and orange peel. Additional ingredients such as almonds, raisins, and sugar are often added to enhance the flavours. This warm and aromatic beverage is served hot and enjoyed in small cups or glasses. Try this recipe for Glögg. Recipes for glögg, glühwein and mulled wine can be easily found by searching online.

Eggnog

Eggnog is a sweet dairy-based beverage consisting of milk, cream, sugar, egg yolks, and whipped egg whites, giving it a frothy texture. It can be made at home or purchased pre-made. Traditionally, eggnog includes a distilled spirit such as brandy, rum, whisky, or bourbon. It is enjoyed as a warm drink during the Christmas season in Canada, the United States, and some European countries, typically from late October until the end of the festive season. In Venezuela and Trinidad, a chilled variation called ponche crema is consumed during the Christmas season.

In the 18th century, eggnog made its way from Britain to the British colonies, where it gained popularity in America. Inexpensive liquor, coupled with the availability of farm and dairy products, contributed to its widespread popularity. Eggnog became synonymous with winter celebrations and is enjoyed on both sides of the Atlantic during the festive season.

Hot Toddy

Hot toddy, also known as hot whiskey in Ireland, is a warm mixed drink typically made with liquor, water, honey, sugar or maple syrup, lemon, herbs (such as tea), and spices. It is traditionally consumed before bedtime, during wet or cold weather, or to alleviate cold and flu symptoms.

The term “toddy” originates in the 1610s from the taddy drink in British-controlled India, made with the fermented sap of palm trees. British colonists brought the recipe back to England, swapping out the palm sap with whiskey, and it became a popular drink during the wet and cold English winters. Some sources attribute the origin of the hot toddy to Irish doctor Robert Bentley Todd who prescribed hot drinks made of brandy, canella (white cinnamon), sugar syrup, and water to patients suffering from cold and flu. In the mid-19th century, the hot toddy gained popularity as a remedy for the common cold. It was regarded as a cure-all, as mentioned in an article titled “How to Take Cold” in the Burlington Free Press in 1837:

“If your child begins to snuffle occasionally, to have red eyes, or a little deafness; if his skin feels dry and hot, and his breath is feverish — you have now an opportunity of doing your work much faster than ever before,” the unnamed writer states. The first step is to avoid calling a doctor. Next, feed the child excessive amounts. Finally, make him drink. “Ply him well with hot stimulating drinks, of which hot toddy is the best,” the writer recommends sagely.

History of Hot Toddy from Vinepair.com.

The hot toddy originally included whiskey but as it made its way across the Atlantic to the American colonies, the preferred liquor changed to rum. Hot toddies are still a favourite drink for the winter season in the UK and the Americas, whether to treat a cold or to warm up on cold, wintry nights.

I hope you enjoyed this article on the delicious world of Christmas/Yule feasts, sweats and treats. The first day of the Yule season approaches in the southern hemisphere on July 1. This day is celebrated in my household with ‘decking the halls’ and the Yule tree, as well as baking traditional Lussinatte food and listening to our Yuletide playlist. We will explore the Scandinavian mid-winter celebrations of Yule, Lussinatte and Jólabókaflóð in next week’s article.

Share this post